The European framing extends to some areas where Angrezabadi could have incorporated materials from earlier Islamic sources. This stands out for the Iberian peninsula (pp. 34–35, 45–46), which he describes as Spain and Portugal without commenting on a connection to Muslims. For North Africa, he recognizes that most people present there today are Muslims, but he describes them as seen by Europeans, as in the comment “most Egyptians are indolent, ignorant, filthily dressed, liars, and ill mannered” (p. 15).

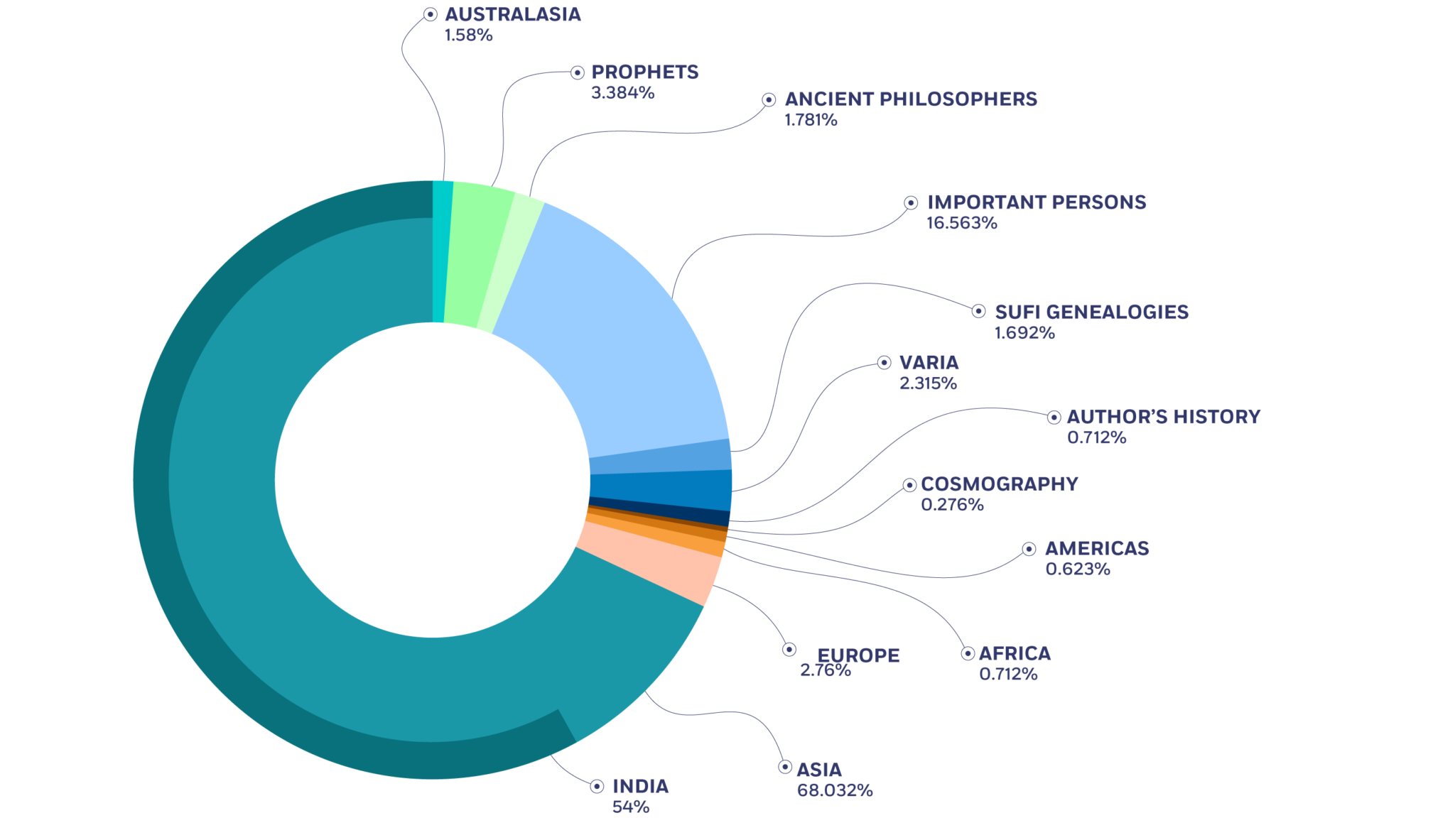

While expansive, Angrezabadi’s coverage of the world is exceedingly lopsided. Nearly seventy percent of the narrative is devoted to the chapter on Asia, a geographical term that is itself a European artifact for grouping together the vast region stretching between Arabia and Japan. Angrezabadi’s description of Asia begins with oceans and mountain ranges, goes quickly over Sri Lanka and some other islands, and then launches into the geography and history of Arabia, which is presented prominently as Islam’s cradle. What follows is a generalized narrative of what is usually regarded as the history of Islam, entwined with the regions today called the Middle East and Central Asia (pp. 57–193). East and Southeast Asia are covered in eight pages, while the treatment of India extends to over six hundred (more than fifty percent of the whole work).

Angrezabadi’s description of India presents the most complex case of amalgamation between information coming from different sources. At a highly generalized level, the geography of India is conveyed through the British divisions of the country, whereas much of the pre-British history is based on Persian chronicles and other sources, used mostly without explicit citation. The British takeover of India is related from the viewpoint of British self-understanding and is said to start with the coming of British ambassadors to the Mughal court in 1600 CE. He describes direct political control over territory as beginning with the seizure of Bengal in 1757 and completing with the defeat of the Sikhs in the Punjab in 1849 (pp. 410–411). Within the extensive description of Bengal, Ilahi Bakhsh provides a detailed account of the vicinity of Angrezabad.

The work’s last chapter is devoted to a description of the author’s own history (pp. 1099–1107). Counterintuitively, this is a list of names and dates, without much in the form of a confession as one might expect in self-writing being penned after the author had completed a work more than a thousand pages long. He states that his family came to Bengal from another part of North India to serve local rulers at an indeterminate date. In the late eighteenth century, an ancestor moved to the region of Malda, where Angrezabad is located, and succeeding generations were connected to Englishmen in the employ of the East India Company. Members of the family seem to have belonged to the middle level of Indian bureaucrats whose literacy skills were in demand for purposes of administration. Angrezabadi remarks that up until 1838, Persian was the language of administration in Malda. Its replacement by Bangla likely diminished the professional prospects of people such as Angrezabadi and his family (p. 539).

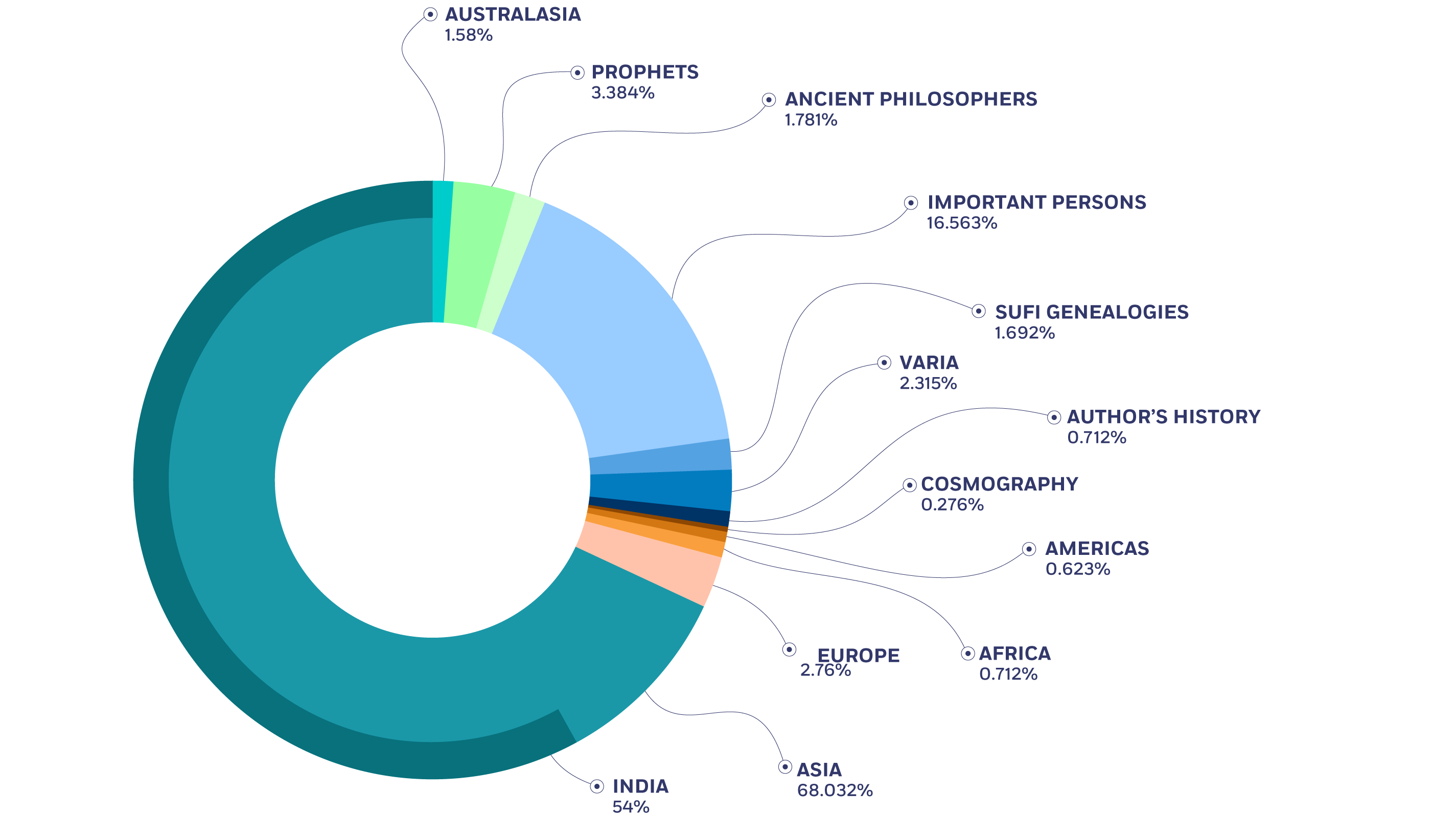

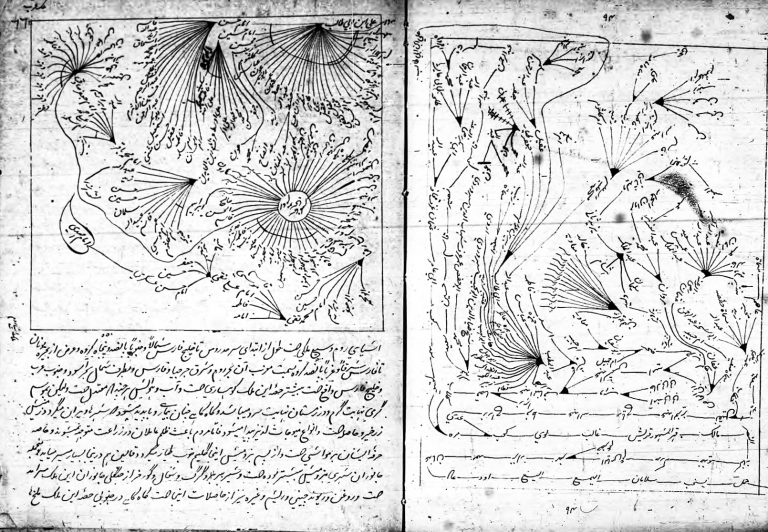

Genealogies of the Prophet Muhammad and the Twelve Shi’i Imams in Khurshid-i Jahan-numa. Exemplifying the author’s historical method, the mapping includes both men and women, filling up the page to encompass linkages rather than putting names in a line or a hierarchical table.

Source

Genealogies of the Prophet Muhammad and the Twelve Shi’i Imams in Khurshid-i Jahan-numa. Exemplifying the author’s historical method, the mapping includes both men and women, filling up the page to encompass linkages rather than putting names in a line or a hierarchical table.

SOURCE

Sayyid Ilahi Bakhsh Angrezabadi, Khurshid-i Jahan-numa. MS Buhar 102, National Library of India, Kolkata, pp. 94-95

The encyclopedic pretensions of the Khurshid-i Jahan-numa can convey the impression that the work is a hodgepodge of materials copied from earlier sources. Such a judgment misses the mark because it means overlooking the distinctive framing invented by the author and the immense labor of excerpting materials from hundreds of works, in multiples languages and genres, to create a compendium. Also noteworthy is that Angrezabadi manages the task of incorporating knowledge from the widely divergent streams.

More than the sheer legwork of understanding and using sources, the Khurshid-i Jahan-numa exemplifies an attitude toward reports on the past that is the inverse of orientalist works such as the Sinin-i-Islam. For Leitner, counting something as history required proof, meaning it had to have a trustworthy source and could stand up to principles of material causality. The first of these applies to Angrezabadi as well, but his method is to let sources speak based on their own cognizance rather than subjecting them to a causality test based on his personal authorial judgment. From this perspective, materials from earlier Islamic, Indian, and European sources all become a part of the same narrative despite issuing from very different places.

The author then becomes a kind of discerning curator rather than someone presiding over the evidence as judge and jury. As I discuss in the section on Mongols in this chapter, this attitude toward evidence for the past originated in particular circumstances and had a long history in Persian works by the time Angrezabadi composed his work. This perspective makes the Khurshid-i Jahan-numa a polyvocal and perspectival account of past time that contrasts sharply with the narrowing and reductive impulse exemplified by nineteenth-century orientalists.

With respect to narrative patterns, Angrezabadi stands apart strongly from earlier Persian works with respect to authors’ self-representation. This is an area where, in the tradition, authors feel licensed to expand on their circumstances as well as emotional states when describing the time when the work was written. But Angrezabadi treats even this topic with a curatorial detachment, providing a list of names and relationships with dates given in both Hijri and Gregorian calendars. The distancing may partly be an expression of genuine humility. However, I think it may also reflect a new subjectivity as a historian.

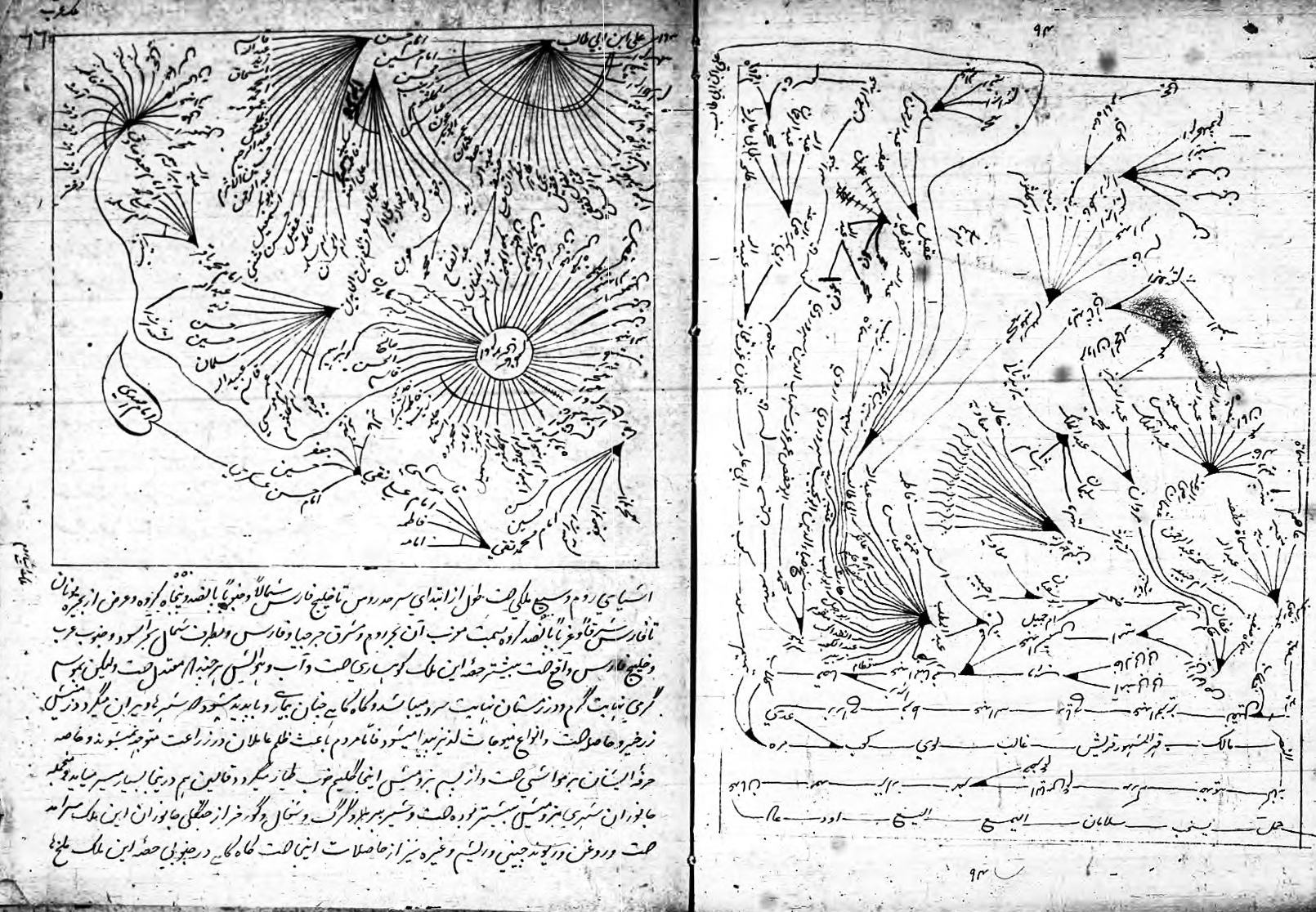

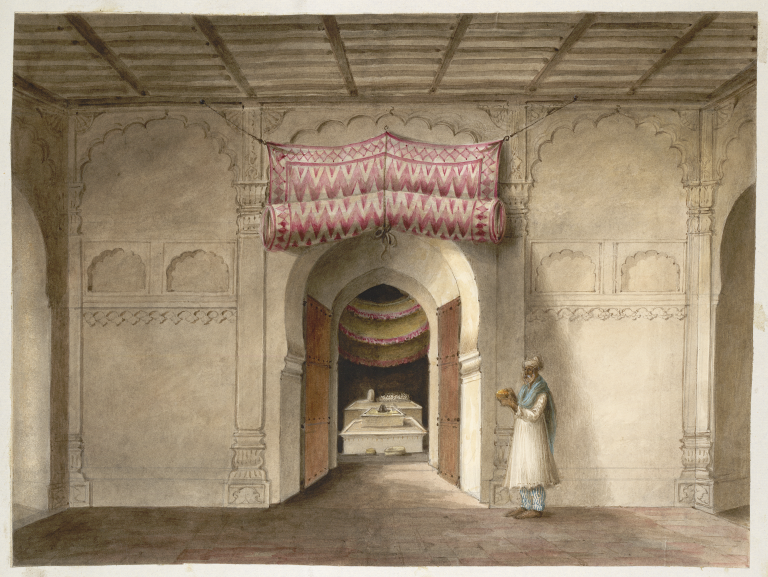

The interior of the Qadam Rasul mosque enshrining the Prophet’s footprint at Gaur. Painted by Sita Ram, 1817.

Source

The interior of the Qadam Rasul mosque enshrining the Prophet’s footprint at Gaur. Painted by Sita Ram, 1817.

SOURCE

© The British Library Board Photo ADD Or 4887

I am inclined to interpret the presentation of self in dates alone, rather than through the more usual recourse to sentiment, as a case of absorbing a new paradigm for thinking about what kind of a past is valuable and worth sharing. This seems especially so because of Angrezabadi’s punctility about giving Gregorian era dates for his family, perhaps adopting a pattern that he would have observed in practices of his European associates.

The only account of someone mentioning meeting Angrezabadi is in Henry Beveridge’s short article on the Khurshid-i Jahan-numa published in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1895. Beveridge writes that in 1889, a Mr. Pargiter informed the Asiatic Society that a Muslim schoolmaster had written a work in Persian that may be worth publishing. The Society invited the author to send the work for inspection, “but the old man was so attached to his book, that he refused to let it out of his sight, and as he could not afford to come with it to Calcutta, nothing further was done at that time” (194).

Beveridge was then able to visit Malda. He met the author and when he suggested copying a part, “he accepted this proposal, and after some difficulty in finding an amanuensis, for Ilahi Bakhsh was too old and feeble to make the extract himself, the portion of it which related to Bengal was copied out and sent to me in England, 1891.” Angrezabadi died in 1892, two years before Beveridge’s report on the text was read out at the Society (Beveridge, “The Khurshid Jahan Numa of Sayyad Ilahi Bakhsh al-Husaini Angrezabadi,” 194–195).

It is moving to think of Angrezabadi as an old man, attached to his Khurshid-i Jahan-numa, a book whose name is a chronogram that indicates it was finished in 1863, more than a quarter century before Beveridge saw it. Written in a language fading fast from the Indian scene, the work was largely meaningless to Angrezabadi’s contemporaries. For Beveridge and others, Europeans as well as Indians, the work’s coverage of places distant from India were valueless. The language and literary form Angrezabadi deployed made the work a relic, a curiosity far more than a source of knowledge. This was an account of the past out of sync with the way the past was meant to be understood and told in the late nineteenth century. This asynchronicity is principally responsible for the work not receiving attention as a unique artifact that speaks to the time in which it was produced. Even more than self-consciously modernist productions, this atypical source illuminates for us particularities of Islam as a historiographical object in modern times.