Islam and History

Hijazi’s novels depict Islam as an utterly this-worldly affair. We never hear of things such as voices coming from the unseen or miraculous powers intervening in human affairs. Since religion is exclusively a matter of human actions, Islam’s meaning must be found in the way Muslims have behaved in the past. This makes history the sole venue from which one can describe Islam and prescribe correct behavior.

History’s significance is emphasized early in Akhri Chatan. The novel’s beginning provides a brief prehistory for Tahir b. Yusuf, the novel’s chief protagonist. Here we learn that his father was born in Medina but journeyed to Jerusalem to join the army of Saladin that was attempting to wrest the city from the Crusaders. While showing great valor in battle, he spent his free time reading books. On one occasion, his Turkish commander mocked him, saying he was acting like the people of Baghdad rather than a soldier. He responded, “The sword is a headstrong horse, for which knowledge is needed as the reins. The people of Baghdad adorn reins but have no horses on which to put them” (18).

As the conversation proceeded, it turned out that Saladin himself was present at the scene, listening from the shadows. Becoming agitated by what was being said, he revealed himself and went on to berate the commander: “I was greatly saddened to hear what you were saying. But you are simply ignorant. Your punishment is that, during any free time in the next six months, you must forsake your companions and devote yourself to reading history. After six months, I will examine you personally. If you satisfy me, you will be promoted. If not, the punishment of solitary study will be extended” (20–21). For a great warrior like Saladin, then, history is a critical part of a righteous Muslim’s arsenal. It must be pursued by all so that they can understand the significance of their actions even in a war.

While Hijazi extols history frequently, this does not pertain to the past in general. What he has in mind are stories of heroic figures of the past with clear implications for the present and future. In the novel, by the time Tahir is a grown man of about twenty-two, the main threat to Islam has shifted from the Crusaders of his father’s age to the Mongols looming in the east. He leaves his home in Medina for Baghdad to fight but discovers that the local people of the great city are still embroiled in bookish debates rather than attending to imminent danger.

Once he has seen more of the world (including a trip to Genghis Khan’s court in Mongolia), he returns to Baghdad and finds the people even more feckless. He is then forced to become a public raconteur of the valuable past:

Pulling the veil from the past, he was pointing to that forgotten place from where the desert-dwellers of Arabia had set out intending to conquer the world. Turning history’s pages, he was relating stories of warriors who had exalted Islam in the east and the west. He was pointing to a storm, hidden behind the future’s curtains, while people listened with bated breath. The eyes of some were damp. A young man could barely control his whimpers. Tahir was saying: “The blackness of ill-luck on the nation’s skirts is washed with blood, not tears. Remember, the way you are living is like playing a joke on nature—and nature never forgives those who mock her” (290).

He is shown especially exasperated by debates about religious particulars since differences of opinion on matters of worship and law create divisions between Muslims. When asked to give his sectarian affiliation, he responds with the following:

For three hundred years, you have been counting types of Muslims and no decision has been made on real and counterfeit, true or false. The reason for this is that you do not measure others on the scale of Islam. Rather, all of you have created your own scales, on which each of you alone measures well.

My dear, it may well be that I cannot think like you because I have little knowledge. I may not be able to fly to high stations on wings of great thought. On the scale you have made for others, I may not measure well, as is likely true of millions of other Muslims. But if you had been riding with me in a battlefield in Khwarazm and had asked me what kind of a Muslim I am, I would have replied that the measure of a believer’s faith is present right in front of us. If I smile under the rain of unbelievers’ arrows, say the profession of faith in the shadow of their swords, if my feet don’t wobble feeling the hand of death next to my jugular vein, then be content: I am a Muslim (291).

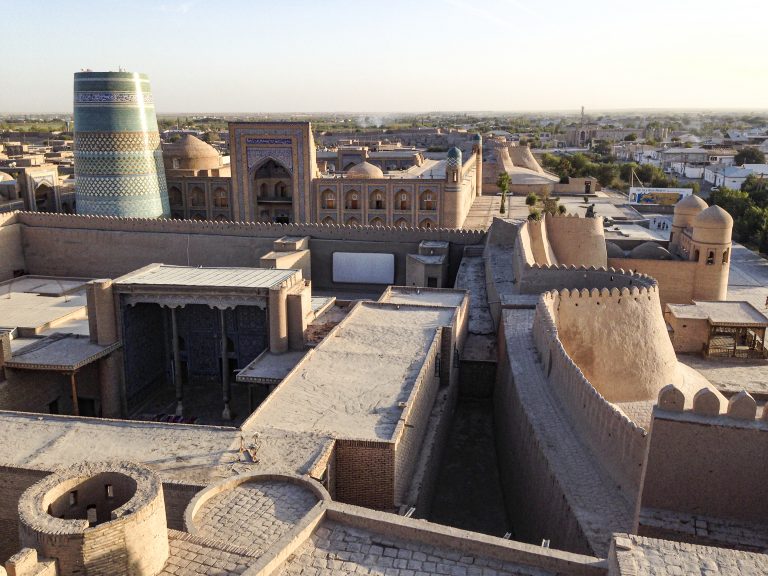

khiva

Khiva, Uzbekistan, was the initial center of the Khwarazmshahi dynasty. It has been preserved as a living museum since the early twentieth century.

SOURCE

Photo © Nancy Hill (2015)

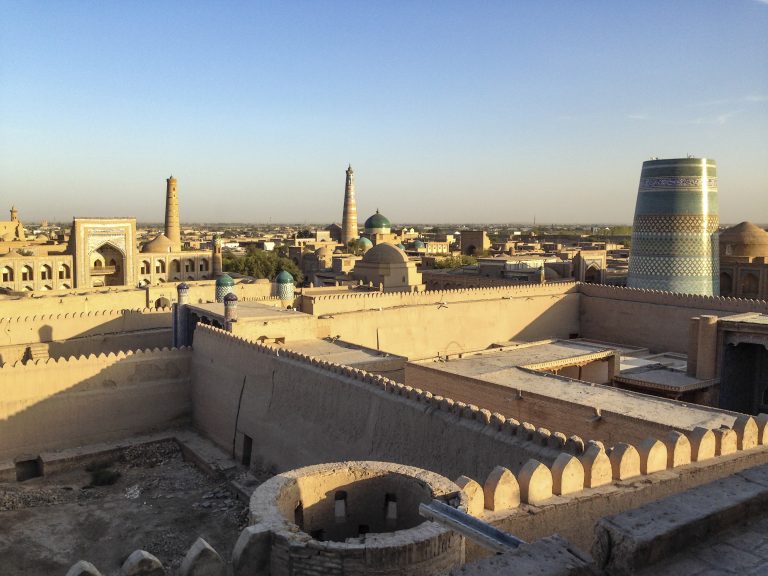

The old fort of Khiva (Itchan Kala) was placed on the UNESCO world heritage list in 1991.

SOURCE

Photo © Nancy Hill (2015)

Khiva has sometimes been used as a set for film and television programs depicting the Islamic past in Central Asia and the Middle East.

SOURCE

Photo © Nancy Hill (2015)

Go to next slide

Go to next slide

Voiced through Tahir, Hijazi’s complaint about Muslim particularities is a common refrain in modern Islamic thought. It reflects a thoroughly sociopolitical understanding of religion in which correct Islam is a matter of belief and action pertaining to communal success against enemies who are always keen to diminish Muslims’ divinely bestowed right to ascendancy. Ritual, theology and philosophy, and psychological interiority are seen as private matters amenable to maximum accommodation. Intellectual effort, in this mode, is directed solely at the outward comportment that materializes Islam in sociopolitical terms.

While concerned mostly with the male domain, Hijazi’s novels do contain women in critical supporting roles. For Tahir’s story, a woman named Safiyya becomes one of his major allies in Baghdad. She protects him during court intrigues and suggests they get married. He declines, citing his duty as a warrior, and she eventually dies as a martyr.

In later exploits, he meets Surayya, a woman who is initially cross-dressed as a warrior while fending for herself and her younger brother. When confronted by Mongol forces, Surayya addresses the men regarding duties incumbent on them especially in relation to women:

Those who are afraid of the Tatars [i.e., the Mongols], I am not prepared to call my brothers. Tell them that a Muslim girl, who has drunk a Muslim mother’s milk, cannot call such cowards her brothers. If they fall short of doing their duty, we will deliver our bangles to them and take up their rusted swords to confront the Tatars. Our love and submission is for the brave, not the fainthearted. If they cannot be the protectors of our honor then they should not expect to stand among God’s preferred at the time of Resurrection.…If they want us to call them brothers pridefully, then they must come before us wearing garments soaked in blood. The faces they show us must have marks of wounds.

The career of Jalal ad-Din Khwarazmshah, a central character in Hijazi’s novel, was made into a Turkish-Uzbek TV serial in 2021.

Source

The career of Jalal ad-Din Khwarazmshah, a central character in Hijazi’s novel, was made into a Turkish-Uzbek TV serial in 2021.

Rousing speeches such as this abound in Akhri Chatan and are a mark of sincere Muslims whose internal thoughts and external speech and actions are always shown to coincide. But relatively few Muslims exhibit these qualities sincerely in the author’s terms. In the end, the sole hope in the form of Jalal ad-Din, son of ‘Ala ad-Din Khwarazmshah, fades from the scene. Tahir’s final admonishment of the people of Baghdad anticipates how they will be seen by people in the future::

People irreverent toward life: see this gale and fire as a warning from nature! You may have heard of the destruction of Babylon and Nineveh, but may God not bring the day when travelers of the future see the ruins of the past and say, there was once here a great city named Baghdad. It had two million people. … People of Baghdad, your caliph and nobles have sold away your and your future generations’ honor and independence to the Tatars for the sake of peace that will last a few years (493).

Such admonishments do nothing to change the balance of forces, and the Mongols continue their march. Tahir and Surayya get married and go to India, where he becomes a renowned general in the army of the Delhi Sultanate. He has sons who follow in his footsteps to become soldiers. He eventually retires from the military career and dedicates the rest of his life to the cause of converting people to Islam in India. While successful in this next phase of his life, he cannot forget Baghdad: “In a gathering or public event, whenever he was giving a speech and remembered Baghdad, he would finish quickly and go sit and brood in some corner. Again and again, he would say to himself, ‘Alas, that I had been able to save that city from destruction!’” (518).

The end of Tahir’s story mixes personal success with communal failure. This combination is a persistent feature of Hijazi’s novels and is the ultimate lesson the author seems to transmit from his exploration of the past in fiction. It speaks to the significance of personal uprightness and perseverance in the face of a world that is unlikely to provide adequate success.

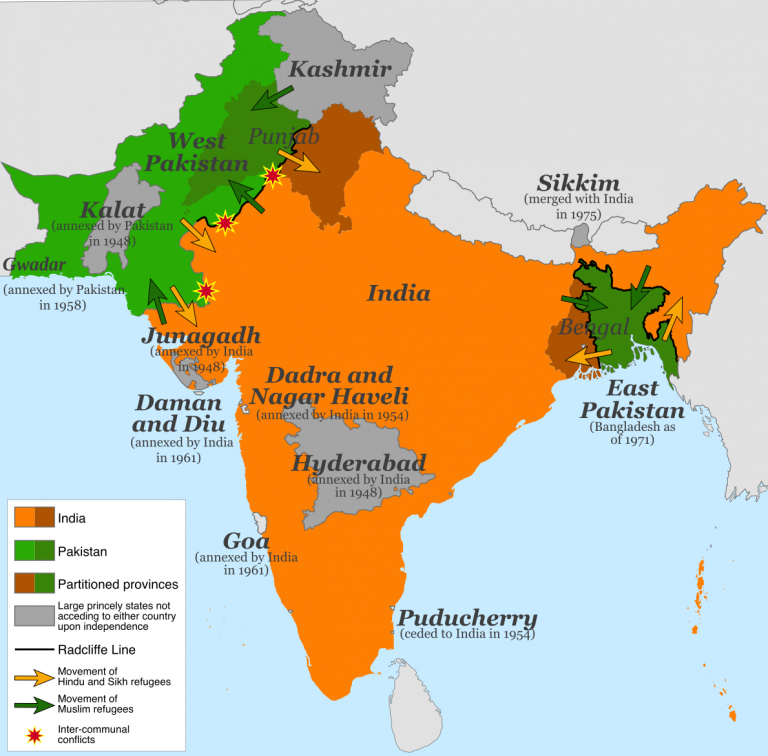

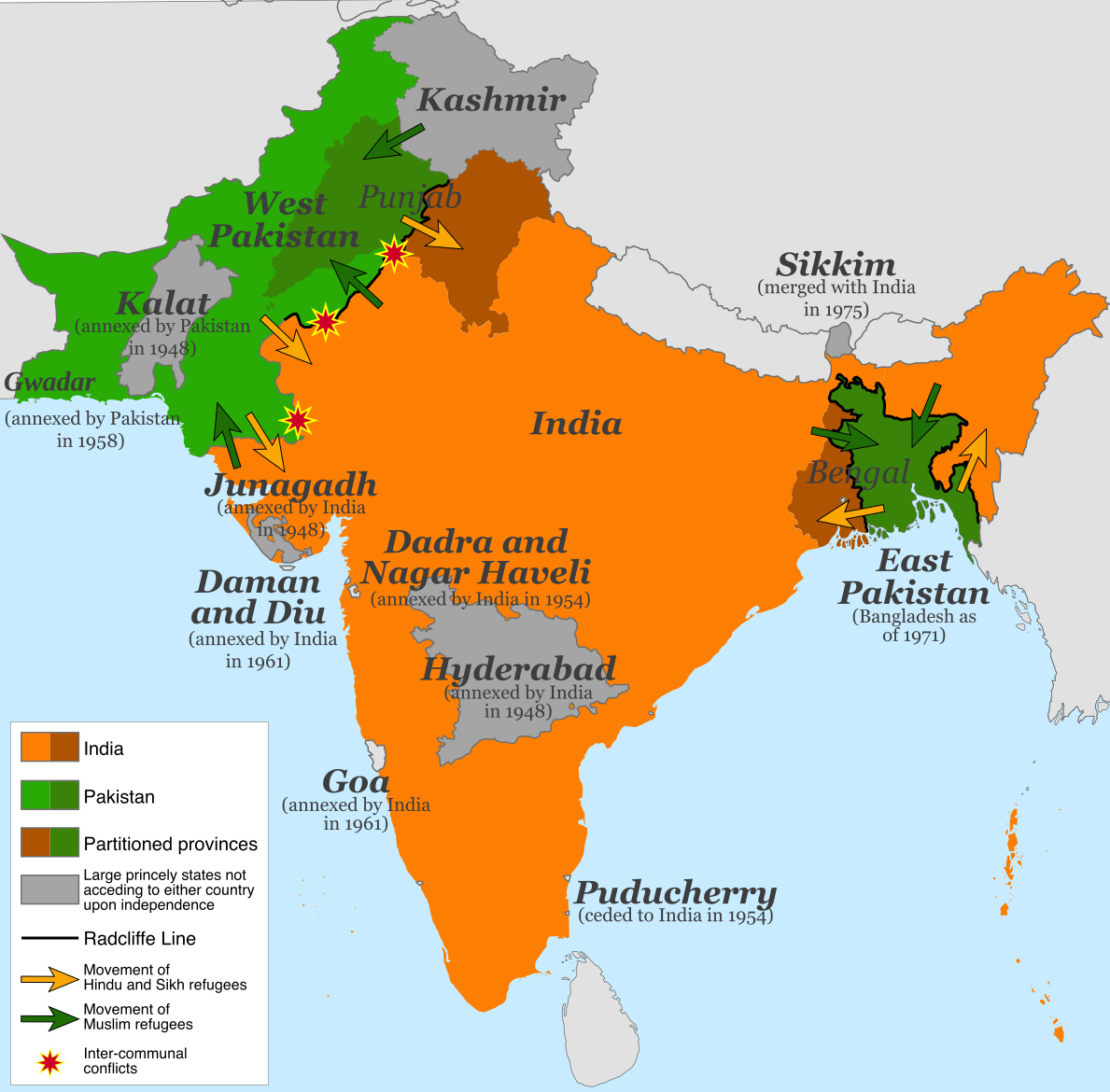

Tahir’s story of an Arab living in successful exile in India has parallels to Hijazi’s own life. Closely correlated to Pakistan’s state ideology, his novels succeeded because they created a form of history ready for consumption by Urdu readers in the second half of the twentieth century. Celebrated as a mouthpiece for religious nationalism in Muslim South Asia, Hijazi nevertheless lived exiled from his birthplace that lay only a few miles away, across the formidable border put in place by partition.