Princess Dhat al-Himma and her Son ‘Abd al-Wahhab

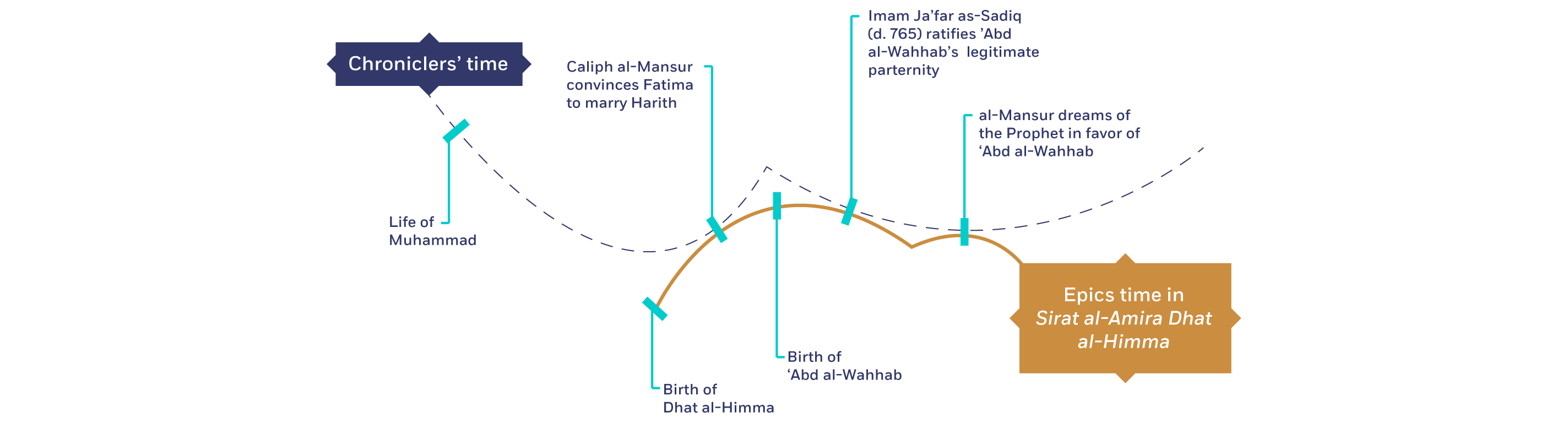

The Arabic epic entitled Sirat al-Amira Dhat al-Himma (Story of the Princess Possessor of Resolve) is thought to be the longest narrative of its genre. It runs to over 5,000 pages in a version that was first printed in 1909 and has now become the standard reference. Literary detective work indicates that the narrative likely originated in northern Syria in the twelfth century CE, although the story it tells hearkens to centuries earlier, namely the period of transition between the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties (ca. 740–800 CE).

Among long-standing Arabic epics, Sirat al-Amira Dhat al-Himma is the only one to have a woman as its main heroic figure. The story, however, is not limited to her alone and contains a vast cast of major and minor characters. As I will discuss, the epic coincides with the chronicle tradition at moments when known historical figures are made to act and talk in it.

To provide the epic’s flavor, I will focus on two pivotal birth stories: one is that of Dhat al-Himma herself and the other of her son ‘Abd al-Wahhab, who later goes on to have a grand heroic career like his mother (Maqanabi, Sirat al-Amira Dhat al-Himma, 7:1–47). Pivotal to the narrative, these births are fraught affairs that lead to the protagonists having precarious lives during their youth. The section of the epic between the two births includes the narrative’s complex negotiations pertaining to gender and inherited versus earned status in the world. The stories also lead to understanding the epic as a counterpart to mainstream chronicles’ portrayal of early Islamic history. The latter is usually an affair tied to Muhammad’s genealogical descendants and the caliphal dynasties that evolved out of the early Islamic polity in Arabia.

Animation summarizing the epic of al-Amira Dhat al-Himma (Samaka Studios, Egypt, 2020).

The scene is set around the middle of the eighth century CE, when two half-brothers, Zalim and Mazlum (the names mean “tyrant” and “victim,” respectively), are contesting inheriting their father’s assets as the chief of the Banu Kilab tribe as the result of a complicated back story. They marry on the same day, and both their wives become pregnant. They come to the agreement that if one gets a son, he would become the chief, but the inheritance would be split if both have sons.

Zalim’s wife gives birth to a boy, Harith, while Mazlum’s wife has a girl. To avoid being disinherited, Mazlum suggests that the child be killed and they say the child was a boy who had been stillborn. The midwife, Suda, is willing to go along with the story. But she saves the child, named Fatima, and brings her up together with her own son, Marzuq. Fatima is the future Dhat al-Himma, a girl braver and stronger than any boy.

When the Banu Kilab are attacked by another tribe, Fatima, Suda, and Marzuq are captured and carried away into servitude. Growing older under these conditions, Fatima’s bravery and beauty cause her to become coveted by a man. When he tries subduing her a second time, she kills him and then goes on to acquire the reputation of a fearsome warrior deserving the title “possessor of resolve” (dhat al-himma).

The tribe in which she is situated as a servant comes into conflict with the Banu Kilab again, and eventually Fatima and her father Mazlum come face to face as enemies. At this point, Suda tells Fatima who she really is, while Mazlum also recognizes Suda and realizes that his opponent is his own daughter. Fatima is then reconciled with her father and goes back to the Banu Kilab with him.

In the story so far, Fatima is a person of ambiguous value. At birth, her gender threatens to disinherit her father, who is willing to dispose of her entirely. To preserve his own status, he shuns her, disinheriting her of her genealogical distinction. The misfortune is compounded when she becomes a captive. But she overcomes these severe disadvantages through her personal qualities. Having earned high status, she becomes an asset for her father in his struggle against his brother Zalim and nephew Harith. Her loyalty as a daughter compels her to show a kind of generosity to her father that he did not extend to her at birth.

Once back among the Banu Kilab, Fatima becomes a part of the politics between her father and his fraternal enemies. Her cousin Harith now becomes obsessed with her and seeks her in marriage, which she refuses on the grounds that she has no need or desire for a husband. At this point, the tribe is invited to the court of the second caliph of the Abbasid dynasty, al-Mansur (ruled 754–775), the founder of the city of Baghdad. Mansur is especially attentive to Fatima and manages to convince her to marry Harith, although she still refuses to have any physical contact with him.

Unable to get his way through pressure or persuasion, Harith becomes aggressive. He bribes Fatima’s trusted companion and foster brother Marzuq to drug her. As she lays unconscious, he rapes her and she becomes pregnant. She is flabbergasted when she wakes up and wants to kill Harith but is stopped by her father. She hides the pregnancy in order not to have any involvement with Harith. Eventually, she gives birth to ‘Abd al-Wahhab, who would go on to be a great warrior like her. Fatima is advised to kill the child lest she is accused of adultery. She refuses to do this and instead sends him into foster care, replicating the circumstances of her own early years.

‘Abd al-Wahhab’s birth has parallels with that of his mother. Although he is legitimate (because Fatima and Harith are actually married), he is also the result of an assault. The mother initially works such that the father is unaware of his existence and hence does not acknowledge him. One of his other attributes is that he is born Black, creating an additional complication with respect to recognizable inheritance. Fatima’s gender and ‘Abd al-Wahhab’s blackness are marks of similar implications.

At six years, ‘Abd al-Wahhab asks for a horse, which leads Fatima to have more contact with him and she begins to train him as a warrior. One of Fatima’s maids discloses that she has a son, leading to an accusation of adultery and, subsequently, to a civil war within the Banu Kilab between the Fatima/Mazlum and Harith/Zalim factions. Eventually, they all go to Mecca to seek clarity regarding the child’s paternity from the wise who live there.

In Mecca, an expert examines ‘Abd al-Wahhab and then identifies Harith as the child’s father after interpreting footprints from many men. When Harith still refuses to acknowledge paternity on account of the child’s skin color, the matter is referred to Ja’far as-Sadiq (d. 765), the sixth Shi’i Imam and leading descendant of the Prophet Muhammad who resides in Mecca and is regarded as the most knowledgeable.

The epic contains an extended account of the interaction between the Imam and the disputing parties. Once Ja’far is agreeable to adjudicate, the case is presented to him in poetry. Dhat al-Himma addresses him first, beginning with the entreaty “today, you are the provision in my state of humiliation.” Harith then responds also in verse, including, “We are white, so from where would we get blackness?” After the two fathers also give their positions, Ja’far examines the child and pronounces him to be Harith’s son. He explains that the difference in skin color between father and son was caused by the fact that Fatima was menstruating when the child was conceived. He then cites a story from the time of the Prophet involving the same issue, stating also that God has the power to cause the change of skin color. If He could cause Jesus to be born when Mary was a virgin, surely everything is within His power (Maqanabi, Sirat al-Amira Dhat al-Himma, 7:36–41).

Harith acknowledges that Fatima was menstruating but still refuses to accept ‘Abd al-Wahhab as his son. The party then ends up at the court in Baghdad again, where the caliph has seen a dream in which the Prophet appears to him and declares that ‘Abd al-Wahhab is being wronged by his father. From here the story veers off toward issues beyond the scope of my current interest.