Dr. Leitner’s History

Leitner had a knack for inhabiting the limelight. A consummate self-promoter, he was treated as a celebrity in his time based on his colorful life story, exceptional linguistic abilities, and high rate of scholarly production. A combative personality, always ready to hector competitors and collaborators alike, added notoriety beyond the confines of scholarly discussions.

To Europeans, he presented himself as a champion of native causes, especially concerning rights pertaining to languages and knowledge. Severely critical of armchair theorists who never left Europe, he prided himself for having traveled to dangerous places, sometimes in a disguise (an interesting counterpart to writing in Urdu) he claims to have managed successfully due to his knowledge of local languages and customs. For Indians and others, he projected himself as an emissary of modern scholarly forms whose inculcation was necessary to revitalize venerable but dissipated cultures. As represented most prominently in the Sinin-i-Islam, he believed that properly understanding the past was an absolute desideratum for an intellectual revival among Muslims in the nineteenth century.

Self-proclaimed orientalists active in the nineteenth century differed widely based on their attitudes to living societies. Some were proud of never having visited the Orient, seeing themselves as masters of literary languages from the distant past whose present forms were irrelevant to their work. Others were keen to combine scholarship and the opportunity for adventure and financial gain made available by the expansion of European empires. Leitner belonged among the latter, a group that also included other highly celebrated figures such as the British Sir Richard Burton (1821–1890) and the Dutch Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje (1857–1936), who both undertook Hajj pilgrimages to Mecca pretending to be Muslims.

Addressing Indian Muslims, Leitner in the Sinin-i-Islam singles out the French Baron Silvestre de Sacy (1758–1838), the Lebanese Christian Butrus al-Bustani (1819–1883), and the self-taught British Edward W. Lane (1801–1876) as scholars whose knowledge of Islamic history and languages surpassed that of any living Muslims (Leitner, Sinin-i-Islam, 1:11–12).

The praise of Leitner’s work in the Calcutta Review identifies two ways to be invested in the past. In tandem with Leitner, it chides Muslims for not knowing enough of their past. But it states also that their failing is that they “too often live on the past.” From this, we infer that the problem is not that Indian Muslims neglect the Islamic past. Rather, they seem to use it as a basis for conducting their lives in the present instead of treating it as an object of intrinsic substance that must be delineated and put at a temporal distance from the present.

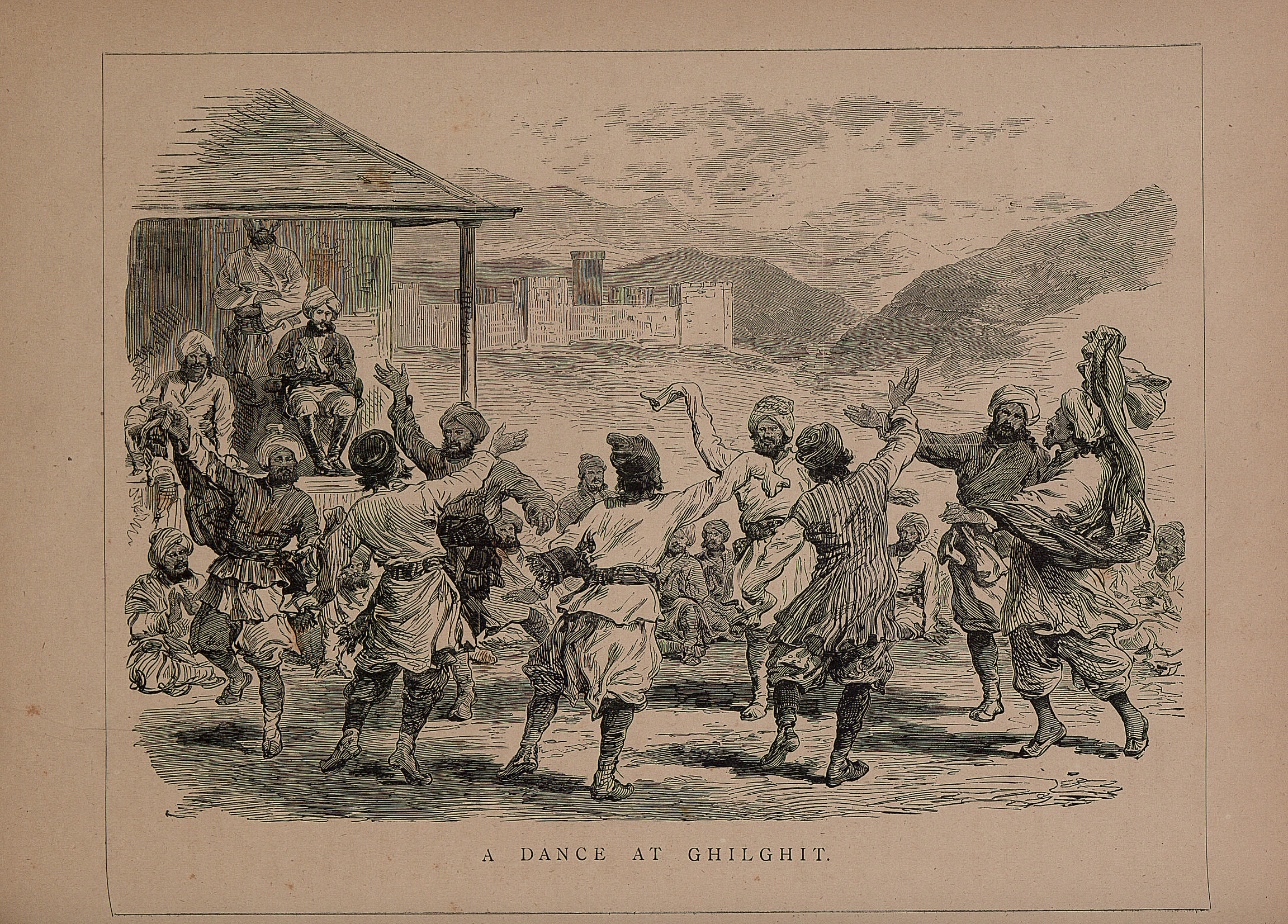

Dardistan

Leitner presiding over a dance at Gilgit.

SOURCE

G. W. Leitner, The Languages and Races of Dardistan. Lahore: Government Book Depot, 1877. p. 31 [digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/leitner1877]

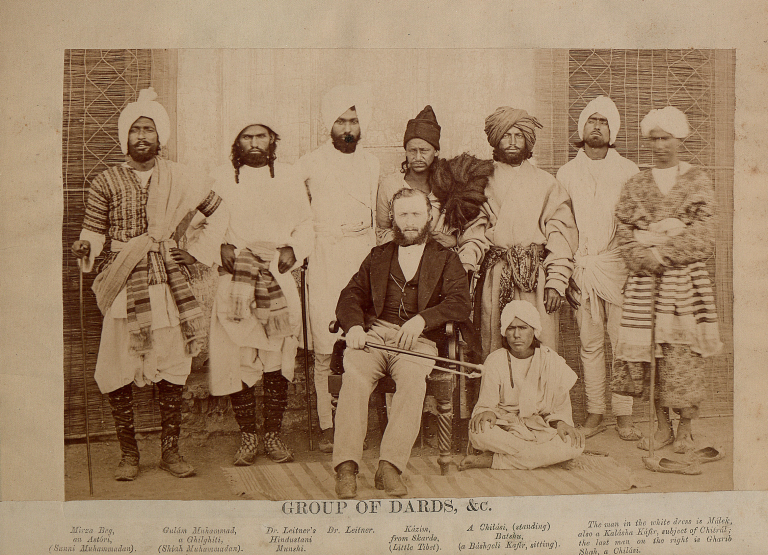

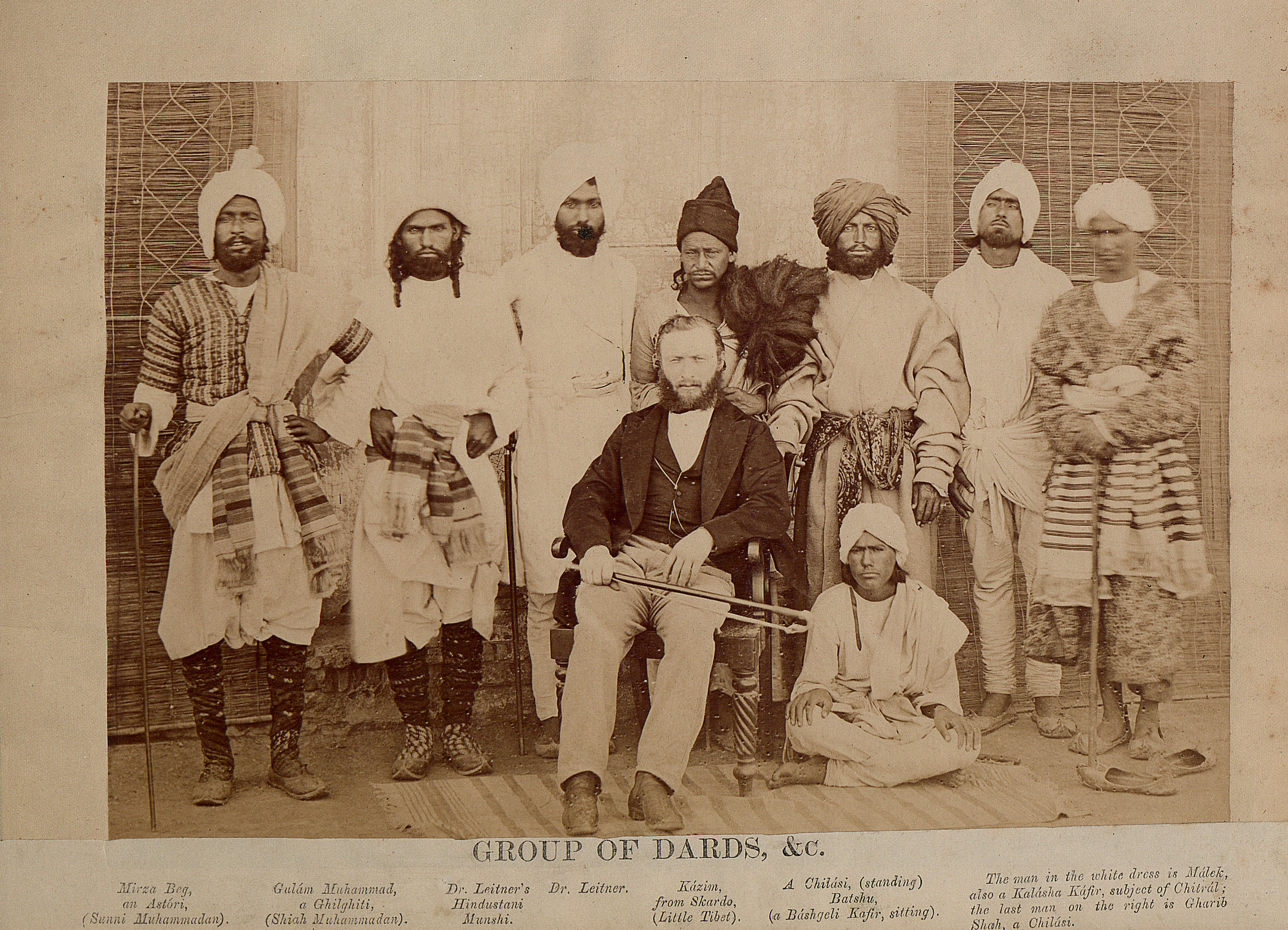

Leitner during his travels in Dardistan.

SOURCE

G. W. Leitner, The Languages and Races of Dardistan. Lahore: Government Book Depot, 1877, p. 12 [digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/leitner1877]

Go to next slide

Go to next slide

The Urdu introduction to the Sinin-i-Islam contains Leitner’s fuller argument in this respect, defining a ”proper” attitude toward history that he considers missing among Muslims. He states the following:

In the world’s register, there is no history without a relationship to the history of other countries. Terminologically, only those events and conditions pertaining to nations that can stand up to proofs are called history (tarikh). There are matters that are correct and proper except that there is no proof for them. These have no relation to history. The history of Islam is not bound to one, two, or three countries. Quite the opposite, its effect runs through all the histories of the world. If not directly, this is through some indirect relation. For this reason, if someone wants to know the history of Islam, s/he should look at world history (Leitner, Sinin-i-Islam, 1:1–2).

A footnote to this text explains further that, to be considered history, occurrences must be placed in a universal frame. By this token, occurrences in China and Japan were not considered history until these places opened themselves to the rest of the world. Similarly, even though America existed physically before Columbus’s arrival, whatever happened there was not history until after 1492. In the case of Islam, Arabs had no history until the rise of Islam. It is only after the coming of Muhammad that the fate of Arabs got connected to those of other entities, such as Rome, Egypt, Persia, Greece, and India. Islam was a kind of sociointellectual mechanism that acted as a conduit to render Arabs historical through incorporation into universal time.

Leitner’s scheme for time was far from idiosyncratic and can be traced directly to philosophies of history in vogue in nineteenth-century Europe. Substantially the very basis for orientalists’ dissection of the world among themselves, its claim for unbiased universality was inextricable from a global account of the past in which Europe was the final bearer of civilizational virtues in the present. Islam (or any other collectivizing descriptor) was historically important only when it could be placed relative to modern Europe.

This posture resulted in two significant imperatives. First, it turned the particulars of Leitner’s understanding of current European history into abstract universals. As he stated explicitly, Europe was in a bad way in the past, a situation whose worst example were the Crusades. Since that period, however, Europeans had forsaken religious bigotry (dini ta’assub) and adopted forms of representative government. Their current intellectual, political, and economic ascendancy, evident from the worldwide dominance of European empires, were a direct result of these changes. Importantly, Europeans had accomplished all this without becoming irreligious. Rather, the Protestant transformation of Christianity meant that they were religious in the correct way, without being impeded by religion’s negative aspects.

Leitner’s prescription was that Muslims must follow a similar path and strip Islam to the basics found in all religions. By doing so, they could occupy the same position in the world as Europeans. The correct understanding of Islamic history was critically important for Leitner’s mission. Objectifying the Islamic past into a proper history meant to root out anything that did not have proof, was not “useful” according to principles espoused by Europeans, and did not fit into the story of universal progress leading up to current European dominance (Leitner, Sinin-i-Islam, 1:6–11).

A history of Islam constructed on this pattern would be synonymous with the universal history of civilization. By extension, Islam would become a name for universal religion, to which only the bigoted among non-Muslims would have any objection. As Leitner stated in an extempore address at South Place Chapel, Finsbury, in 1889, Muhammadanism “is pure Judaism plus proselytism, and original Christianity minus the teaching of St. Paul. … [H]e is a better Christian who reveres the truths enunciated by the Prophet Muhammad” (Leitner, Muhammadanism, 5, 12).

Gothic building of Government College, Lahore, 1880. Leitner was principal of the college between 1864 and the late 1870s.

Source

Gothic building of Government College, Lahore, 1880. Leitner was principal of the college between 1864 and the late 1870s.

SOURCE

© The British Library Board Photo 355/1(224)

The second major consequence of Leitner’s perspective on civilizations was that it required Islam to be evacuated of certain types of specificity. In the historical context, all that could be particular to Islam were names of peoples and groups professing belief in it. These could be extracted from chronicles and other sources. The sources’ contents other than names were then to be judged based on what counted as proof according to nineteenth-century epistemological principles. A kind of universal sociology pertaining to matters such as the relationship between the rulers and the ruled, competition among elites, and so on, whose principles were derived from views on European societies and history, was the ultimate arbiter of value in the Islamic sources. Whatever else was there—contents of differences of opinion among intellectuals, dynamics specific to the societies in question, and so forth—was more than what could be accommodated in this version of history.

The Sinin-i-Islam lives up to this prescription quite well, which is precisely why it would have appeared vacuous to its intended audience. Not only did it fail to provide a past on which to live—as Muslims were accused of doing as a major shortcoming—but its narrative drive was also meant for an orientalist audience who could find the same story told better and in greater detail in European languages.