The Recalcitrant Mosque

Nancy Florida’s book Writing the Past, Inscribing the Future: History as Prophecy in Colonial Java is among the finest scholarship to analyze a complex literary work claiming to represent the past. The book contains a translation and detailed analyses of the Javanese Babad Jaka Tingkir, an anonymous account in verse inscribed in the mid-nineteenth century but claiming to represent occurrences from the early sixteenth century. Although in a form recognizable as traditional, the work takes up a radical posture on its objective:

Rather than register a recuperation of past reality in the name of “objective truth” (as do many conventional master-narrative historical projects of the West), or a reinscription of the imagined pasts of dynastic presents with an eye to continuing traditional status quos (as do many of the more mainstream works of indigenous Javanese history), this text constructs an alternative past which, countering its oppressive colonial present, would move toward more autonomous, perhaps even liberating, futures (Florida, Writing the Past, 10).

A theatrical reenactment of the story of Jaka Tingkir in Java, Indonesia.

Source

A theatrical reenactment of the story of Jaka Tingkir in Java, Indonesia.

SOURCE

Photo 46022305 © Miko Bagus | Dreamstime.com

The work accomplishes its task through its form and the episodes it chooses to narrate. Its title translates to The History of the Youth from Tingkir, ostensibly making it an account of Sultan Pajang (d. 1586), a figure well known in Javanese lore as the first Islamic king in the island’s interior and a precursor to the powerful Mataram sultanate (1587–1755). I say ostensibly because the sole surviving manuscript of the work, which stops midsentence, seemingly unfinished, takes us only to the point where the Youth from Tingkir (Jaka Tingkir) is a recently orphaned infant.

What the work provides is actually a prehistory of the hero, whose own exploits would have been known already to the Javanese audience likely to read the work. In Florida’s portrayal, the work’s inconclusiveness is prefigured in what the author says from the very beginning and is our clue to regard it as a narrative about the past attempting to imagine a future away from the colonial circumstances facing its author in nineteenth-century Dutch East Indies. The infant whose story is left dangling at the work’s end is both a past hero and the potential savior alive in the present who can transform the future.

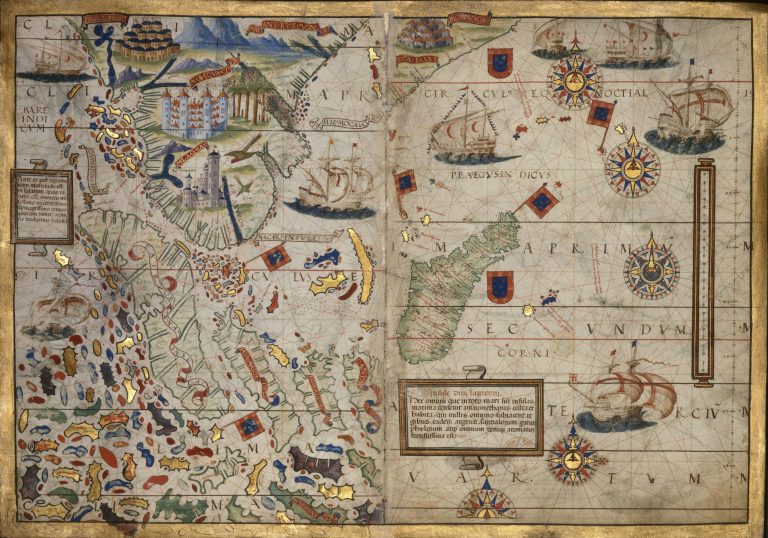

The narrative of the Babad Jaka Tingkir consists of six loosely connected episodes about the past whose frames and contents both feed into the work’s purpose (Florida, Writing the Past, 285). The work’s seemingly disjointed surface is attributable in part to the fact that the author is relying on the audience’s prior knowledge to fill in the gaps. For the discerning reader, the work is meant to act as context for the already familiar text of the past. As a series, the episodes parallel Java’s transition from being ruled by the Hindu-Buddhist Majapahit empire (1293 to c. 1500) to the predominance of the Muslim rulers of Demak.

The first two episodes are focused on the king of Majapahit and his descendants, while the main characters in the remaining four are identified as Muslims. In the work’s portrayal, the arrival of Islam in Java is incidental, as some members of the Majapahit ruling family are said to convert. But in the third episode, the establishment of Islamic rule and religious authority is given central billing through the extensive account of the construction of the great mosque of Demak. This episode provides the clearest picture of the work’s sense of Java as an Islamic spacetime, reflecting both Javanese Muslim self-understanding of origins in the nineteenth century and the author’s political aspirations for a future different from the present in which he or she was writing.

With all its symbolic significance as a place of Islamic origins in Java, the mosque of Demak is not datable based on the timeline model of the past. It lacks easily decipherable evidence, which modern historians have adjudicated by lamenting the absence of records or using generalized conjecture or approximation to elide the gap between internal evidence and Common Era homogenized time. If we resolve to bracket this paradigm, the evidence we have turns into a trove of possibilities connected to varying senses of the past associated with the monument.

outside

Demak mosque.

SOURCE

Photo © Shahzad Bashir (2015)

Interior courtyard of Demak mosque.

SOURCE

Photo © Shahzad Bashir (2015)

Drum for calling to prayer in Demak mosque.

SOURCE

Photo © Shahzad Bashir (2015)

Go to next slide

Go to next slide

Confusion regarding the mosque’s date of origins is rooted in the way scholars have interpreted elements found in the building and narratives as possible chronograms. The first point to be made here is the very notion of a chronogram, a practice widespread across the Middle East and Asia, according to which a date is encoded into text or image. For a date to deserve this requires that it be qualitatively extraordinary, marking a moment that stands apart from other moments before and after it. Dates made into chronograms are thus meant to be interruptive, defying the notion of homogeneous time by definition. To see a chronogram as a straightforward point of the data on a standardized calendar is to overlook an important piece of information.

Interpreters have attempted to date the mosque in Demak through reference to four mutually inconsistent chronograms. Three of these are “concealed,” meaning they are visual and the interpreter gets to a text by first figuring out the words to be used for what is seen. These involve the following: 1) dragons engraved on the mosque’s doors that may be read as 1466, 2) the image of a turtle on the wall of the mihrab that faces Mecca that may give 1479, and 3) the image of lightning also on the main doors that leads to 1506. The fourth is a textual chronogram that comes from a work entitled Babad Demak (Chronicle of Demak) that has been interpreted as 1407. As scholars familiar with chronograms have argued, the interpretations that lead to the various years are far from definitive, leading to a level of ambiguity that sits atop the fact that we are already unsure whether to place the origins in 1407, 1466, 1479, or 1506 (Wieringa, “A Monument Marking the Dawn of the Muslim Era in Java,” 168–174).

The Babad Jaka Tingkir provides an account of the mosque’s construction far apart from anodyne discussions of years on a calendrical scale. Here the mosque is treated as a pusaka or talisman whose coming into being transforms its surrounding land and is meant to condition Java’s future. In the narrative, the environs of Demak are said to have had a mosque already, though a bigger one is needed to mark the community’s expansion both numerically and in sociopolitical significance. Muslim elites of the region—both religious and political—gather to undertake the task under the leadership of Sunan Bonang. Those attending get classified into categories assigned different functions.

Eight premier religious guides (including Sunan Kudus) are made responsible for the four pillars of the central sanctuary, while lesser religious figures and kings and princes from all around are tasked with making pillars for the building’s peripheral parts as well as other elements of construction. All undertake the jobs assigned to them assiduously except for Sunan Kalijaga, one of the Wali Songo who is a maverick among the saints and is also called Sèh Malaya. When reprimanded by Sunan Bonang for dereliction of duty, Sunan Kalijaga compels leftover scraps of wood to congeal together into one of the four pillars of the main sanctuary.

Sunan Kalijaga’s signature miracle culminates the process of manufacturing materials for the mosque. After a bit of rest, the whole group works together to join the pieces to create the building. This narrative conveys not just the creation of a building but also the establishment of the whole social hierarchy associated with Javanese Islam. The living bodies that create the mosque in pieces and then assemble it are constructing a socioreligious edifice meant to mark a new present and future for the land. The self-consciously symbolic narrative we see in Babad Jaka Tingkir is a mid-nineteenth-century version of the community’s story of its own origins that had been in circulation for centuries.

As a monument central to Islamic religiopolitical identity, the Demak mosque bears comparison to the Ka’ba in Mecca. This aspect is dramatized in the narrative through the story of how the mosque is made to orient toward Mecca. The direction toward Arabia, required of mosques, proves challenging because authorities present on the scene differ in their views. After much discussion, the chief saints decide to take time out to meditate to find a solution to their dispute. This effort reveals the correct direction through spiritual intuition, which they then proceed to fix.

But now another problem arises in that the newly constructed mosque refuses to align in the right direction even though the Ka’ba has miraculously appeared on the scene and is in the saints’ field of vision. This leads Sunan Kalijaga (Sèh Malaya) to force the two buildings to acknowledge each other. The following is Florida’s translation of the narrative:

inside

Mihrab with turtle chronogram in Demak mosque.

SOURCE

Photo © Shahzad Bashir (2015)

Four pillars that hold up the roof of the inner sanctuary of Demak mosque. The original pillars are now in a museum attached to the mosque, and these are replacements.

SOURCE

Photo © Shahzad Bashir (2015)

Go to next slide

Go to next slide

Condensed the world was tiny

And Mecca shone close by

Allah’s Ka’bah was nigh, manifest before them

To estimate its distance

But three miles off it loomed

The Celibate Lord did beckon

Sèh Malaya, ware to the subtle sign

Lord Sunan Kali rose to his feet

From north he did face south

One leg he did extend to side

Both legs did stretch forth

Long and tall, their stance astride

His right foot reaching Mecca came

Just outside the fence of Allah’s Ka’bah there

His left foot did remain behind

Planted to the northwest of the mosque

Allah’s Ka’bah did his right hand grasp

His left hand having taken hold

Of the uppermost peak of the mosque

Both of them he pulled

Stretched out and brought to meet

The Ka’bah’s roof and the peak of the mosque

Realized as one being were

Perfectly straight strictly on mark

All the great and mighty wali

Watched in exultant joy

Lord Sunan Bonang softly said:

“Little brother Sèh Malaya, now

‘Tis right beyond a doubt”

Sèh Malaya did a sembah make

Then his hands released

Allah’s Ka’bah and the mosque returned, each to its own place

Then Sèh Malaya sitting down

Before his elder brother made a sembah (Florida, Writing the Past, 167)

An instance of the manufacture of space, this evocative narrative accomplishes something seemingly ordinary in Islamic terms. After all, mosques around the world have been made to orient toward Mecca through geometric calculation for centuries. The special aspects here are that the invisible line that connects a mosque to Mecca becomes visible as the saints present in Java can see the Ka’ba, and Sunan Kalijaga must force both buildings to move to create the correct alignment. In the symbolic sense, then, the creation of the mosque in Demak changes the monument in Mecca as well.

power

Graves of the kings of Demak next to the mosque.

SOURCE

Photo © Shahzad Bashir (2015)

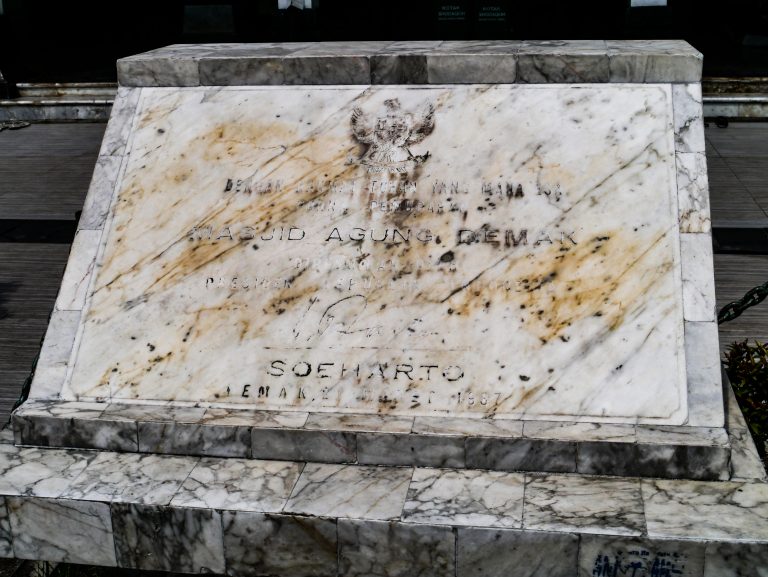

Plaque commemorating the Demak mosque’s renovation by the order of Indonesia’s president Suharto in 1987.

SOURCE

Photo © Shahzad Bashir (2015)

Go to next slide

Go to next slide

The Demak mosque’s elaborate physical structure, meant to mirror and sacralize Java’s sociopolitical hierarchy in an Islamic vein, causes a shuffling of the original holy land. Constructing Demak in Mecca’s image—and Kudus in that of Jerusalem—the founders of the Muslim community in Java in the Babad Jaka Tingkir are responsible for a global rather than a local commotion. When we read this work as an anticolonial prophecy, as Florida suggests we should, the narrative contains a sixteenth-century past, with a presumed triumphalist future, that is to act as prescription for what can happen in Java in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Fluid Spacetimes

We can now briefly compare Pires and Babad Jaka Tingkir to draw out the significance of variation in spacetimes. While both these sources claim authoritative knowledge about the presence of Muslims in Java, their portrayals vary radically based on matters such as authorial background, purpose, and the desired effect on the presumed audience. These matters pertain to the works’ underlying conditions of possibility, which can, in turn, be seen to reflect the authors’ social and intellectual investments at the level of foundational cosmology. In Pires’s account, the story of Muslims in Java (and other places in Asia he visits) are a continuation of what he knows about Iberia. Muslims are Moors, wherever encountered, even though this term would likely mean little to the people he is describing. His narrative contains a kind of collapse between Java and Iberia that is, moreover, rooted in a temporal transposition.