Timeline as Historical Form

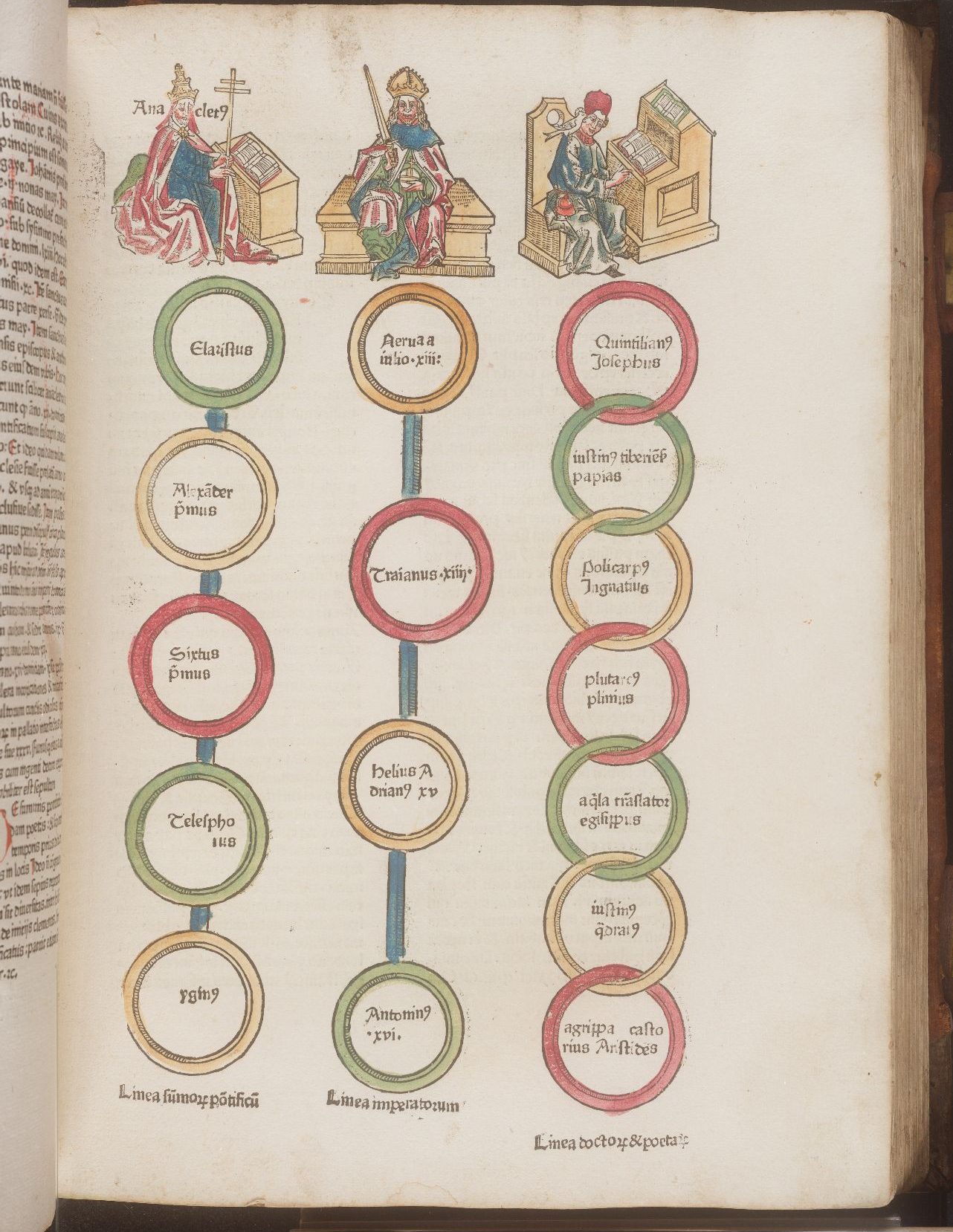

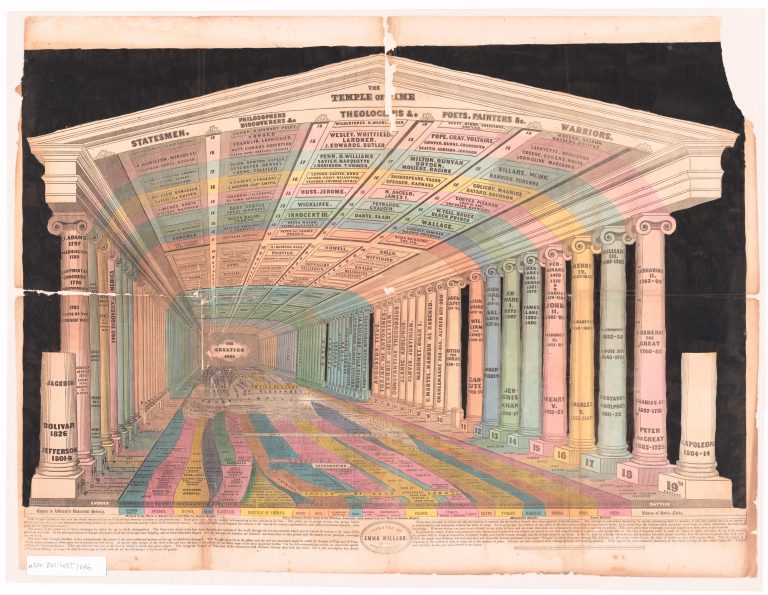

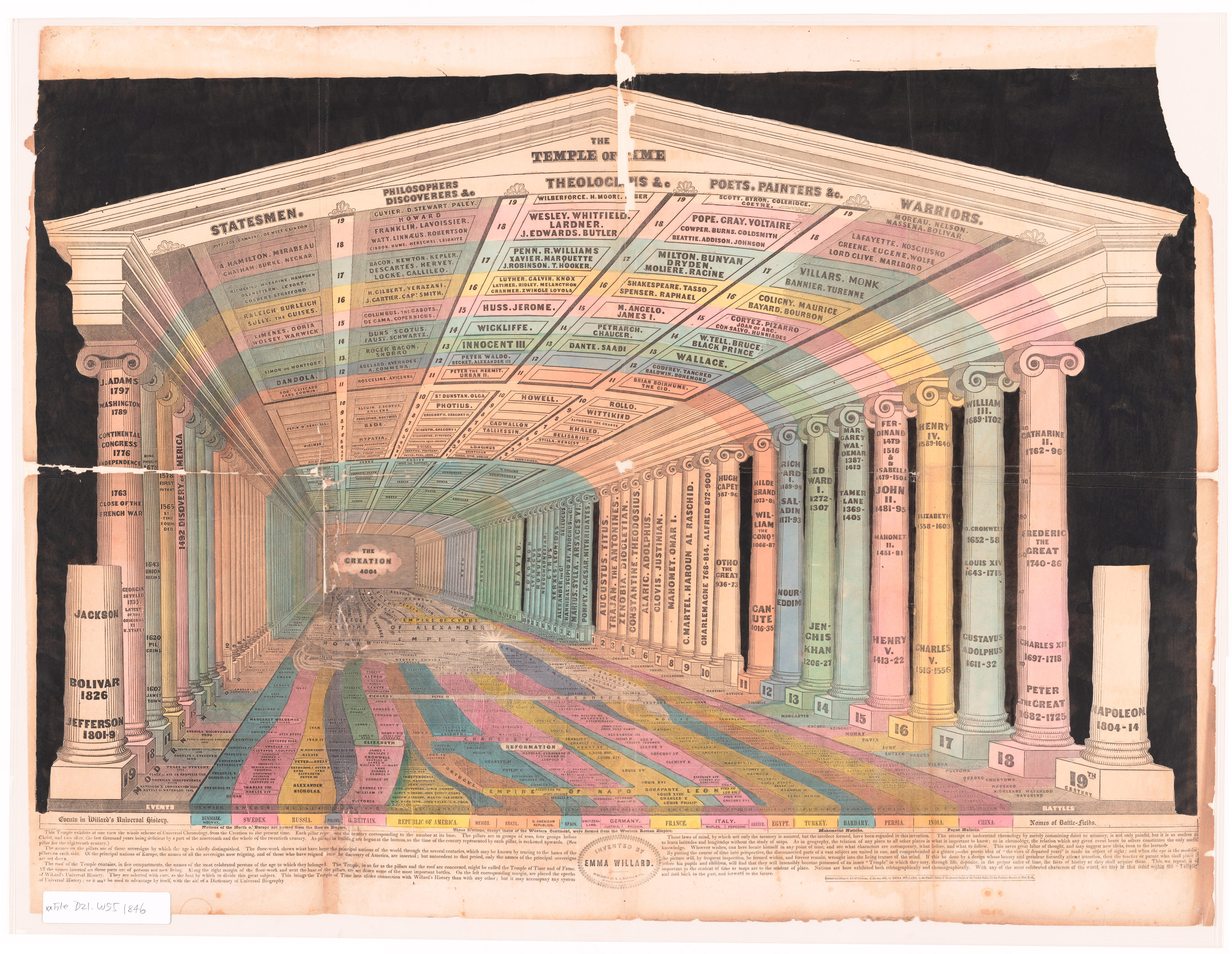

Emma Willard (1787–1870) was a brilliant author and educator with a long career as a promoter of women’s education in the United States. Her Temple of Time, published in 1846 in the United States, is a mnemonic conspectus of universal history. The image of a temple in classical European style presents the intersection of three hierarchically arranged temporal orders: the building’s pillars mark Common Era centuries, representing abstract time; inscriptions on the pillars (rulers) and lists inscribed on the temple’s ceiling (statesmen, etc.) tether biographies to abstract time; and twisting columns containing text, which snake across the temple’s floor, encapsulate destinies of groups identified as nations (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, etc.) in correlation with abstract and biographical times.

The density of information contained in this graphic reflects the variety and complexity of discourses about the past that needed to be assimilated by an educated person in Euro-American societies in the nineteenth century. However, the distinctively modern element here is not the comparison between pasts coming from multiple sources. This was a concern for many premodern chroniclers and philosophers as well, among them Europeans and Muslim polymaths such as Abu Rayhan al-Biruni (d. ca. 1050) and Rashid al-Din Tabib (d. 1318).

Emma Willard’s Temple of Time.

Source

Emma Willard’s Temple of Time.

SOURCE

New York: A. S. Barnes, 1846, scan courtesy of Amherst College Library

The temple’s modernity resides in the timeline that is invisible in itself but forms the basis of the serialized placement of pillars marking the passage of impersonal time. Everyone looking at the image is presumed to have an intuitive grasp of this timeline as the image’s understructure. While expert viewers may disagree regarding text placed across the surfaces of the architectural elements as being a part of the graphic, they would consider the structure of time beyond dispute. Similarly, novices are presumed to know that time progresses regularly and are pushed to treat this as the basis for acquiring universal knowledge about the past.

For the creator and the presumed viewer of the temple graphic, abstract time has a totalizing yet agent-less authority over other temporal scales, such as lifetimes and narratives shared among religious communities and nations. I propose that to derive richer understandings of Islamic and other pasts, we must dismantle the presumed logic of representations such as the Temple of Time.

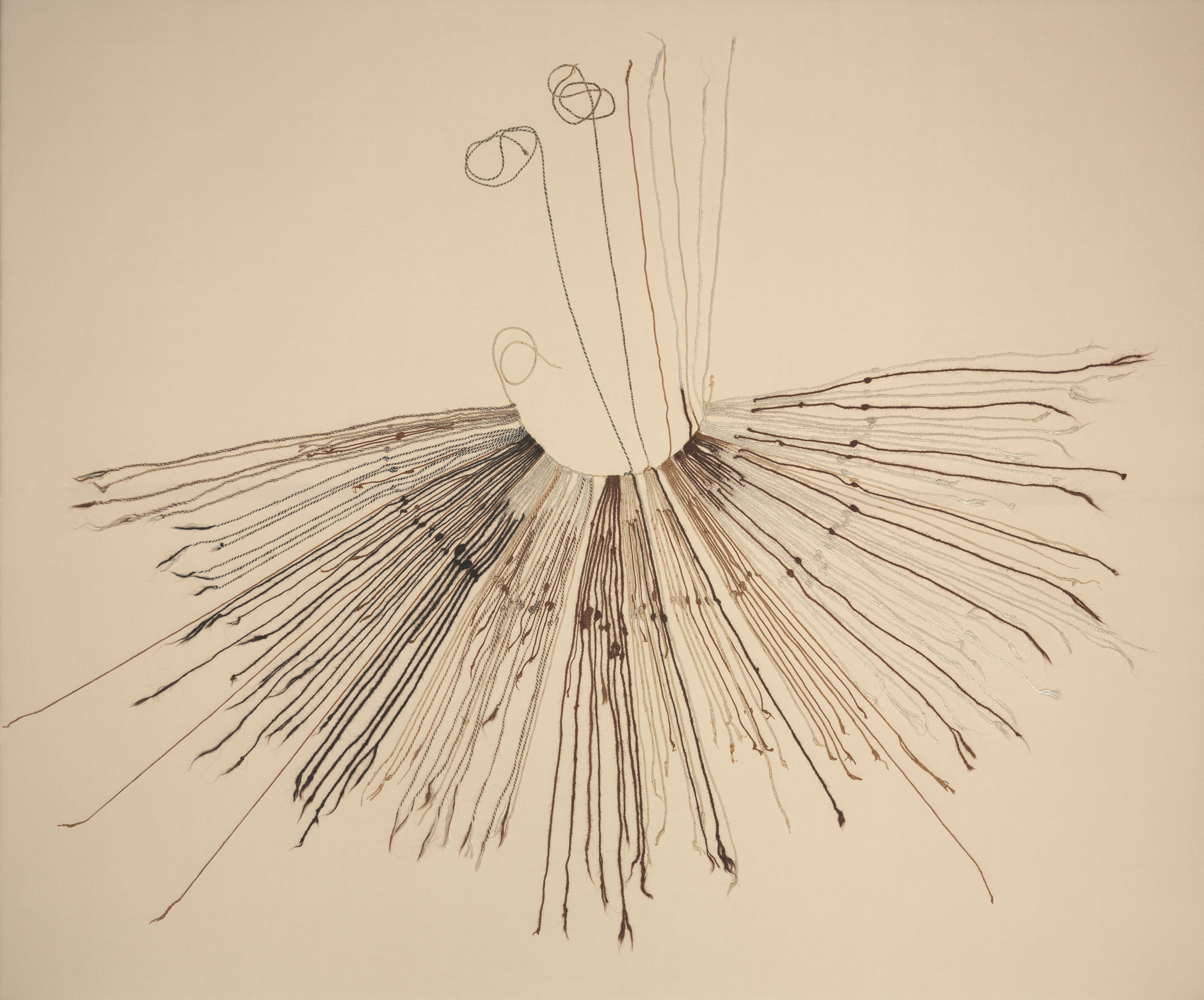

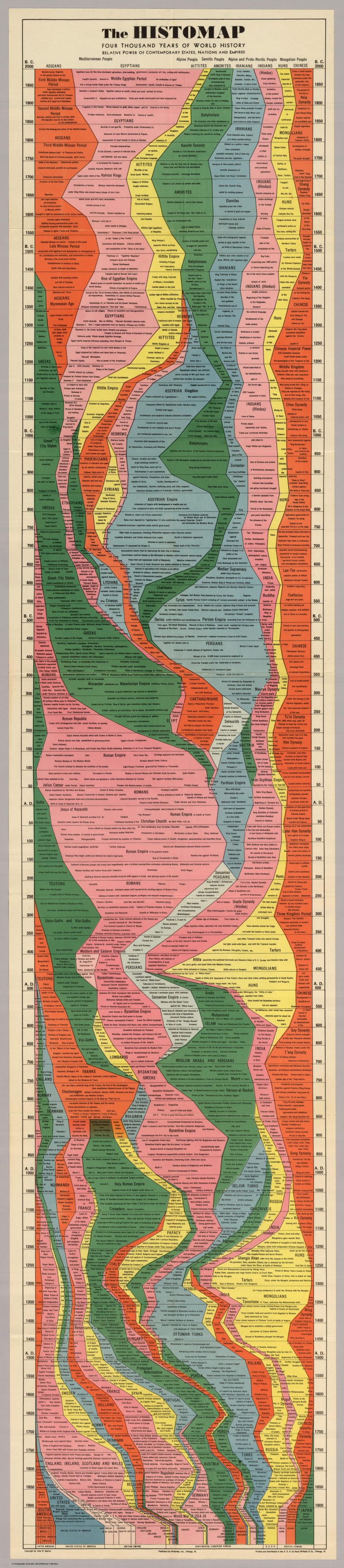

In addition to the primacy of abstract time as the scale, other aspects of the worldview exemplified in Willard’s graphic need recognition. Corresponding to the floor of the Temple of Time, these are seen more easily in The Histomap, a graphic representation of world history published in the United States in 1931. Abstract time dominates here as well, represented in the scale covering 4,000 years that runs vertically along both sides of the map. In between the scale’s regularity, we see lines twisting and tortured, representing what the work’s title refers to as “Relative Power of Contemporary States, Nations and Empires.” By looking horizontally between the years marked on the vertical axis, the viewer gets a snapshot of the relative balance of power between entities existing contemporaneously at a given moment on the scale.

While we are not provided a definition for “power,” the condensing of four millennia into a chart is based on a qualitative progression leading up to the global dominance of powers identified with Europe that have the widest presence at the very bottom (United States, British Empire, Continental Empires, and the USSR). The material wealth and technological capacity that allows these entities to dominate the world are the implicit definition of strength. Even as time continues its unconcerned march in the abstract scale, The Histomap gives history a purpose, which is to explain, and justify, power structures pertaining to human beings prevalent at the time the map was generated.

The Histomap.

Source

The Histomap.

SOURCE

John B. Sparks, The Histomap: Four Thousand Years of World History. Relative Power of Contemporary States, Nations and Empires. Chicago: Rand McNally and Company, 1931. Scan courtesy of the David Rumsey Map Collection, Stanford Libraries

Underlying modern universal time—impersonal in scale but imbued with the power relations of the modern present—is the principle of material causality purportedly observable through scientific methods. Since the nineteenth century, this understanding of causality has acted as the touchstone for differentiating between the plausible and the implausible regarding claims about the past. Formulated in visions of progress or conservatism, and of development and stasis, the same principle has helped shape varying visions of the future.

Pasts and futures tied to timelines via investment in material causality have been the seemingly natural way to comprehend phenomena at any scale. At a micro level, causality presumed within the timeline is central to matters such as the detective novel and the modern science of forensics. In grander terms, its effects can be seen in understandings of biological evolution, theories of economic change, and sociopolitical dominance represented in documents such as the Temple of Time and The Histomap.

The ramifications of causality in this vein have not resulted in investigative naïveté. I am not suggesting that the notion of history as a modern science is a blind ideology or conspiracy. In fact, since the nineteenth century, the number and complexity of causes that can be invoked to make sense of observed data feeding into timelines has become greater and greater. Investigators operating on the basis of material causality have usually realized that figuring out one connection spurred them toward looking for others. However, even absolute uncertainty in this perspective is premised on the imagination of time as a unidirectional line. The observer’s frustration over the inability to substantiate the causes for an occurrence belie the foundational expectation that such causes must propel linear temporal progression in a single direction.

The important thing here is the epistemological pattern that connects material causality to the notion of time as an impersonal series of moments. The ascendancy of the timeline as a modern interpretive and representational mode and its underlying presumptions about causality has had specific consequences for the way Islam has been imagined.