Shi‘i Imams as Genealogical Heirs to the Prophet

Expanding our purview beyond Kudus, we can get a more particularized sense for what is understood as being conveyed within genealogies by looking at Shi’i traditions about the Imams. Since the status of the Imams is crucial for Shi’i thought, its justification was the most emphatic form of affirming the authority of Muhammad’s genealogical heirs. The significance of sayyids as a class can be presumed to rest on similar, but often weaker, cosmological and epistemological understandings.

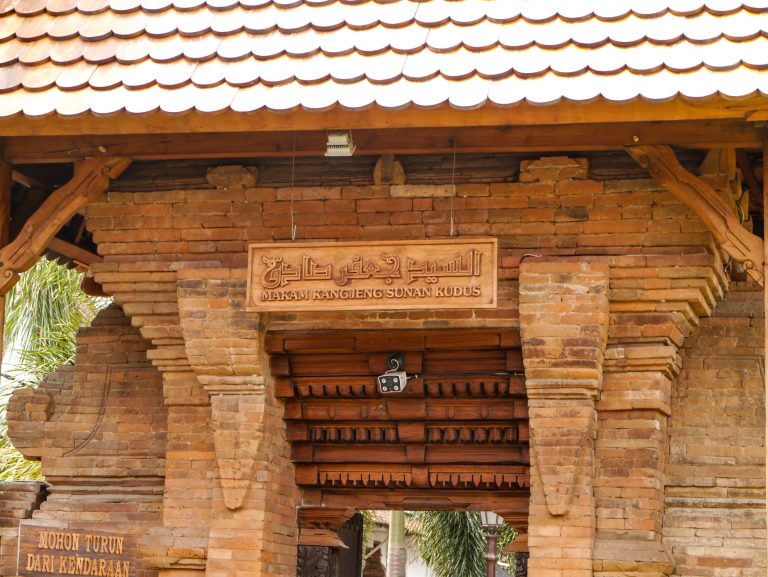

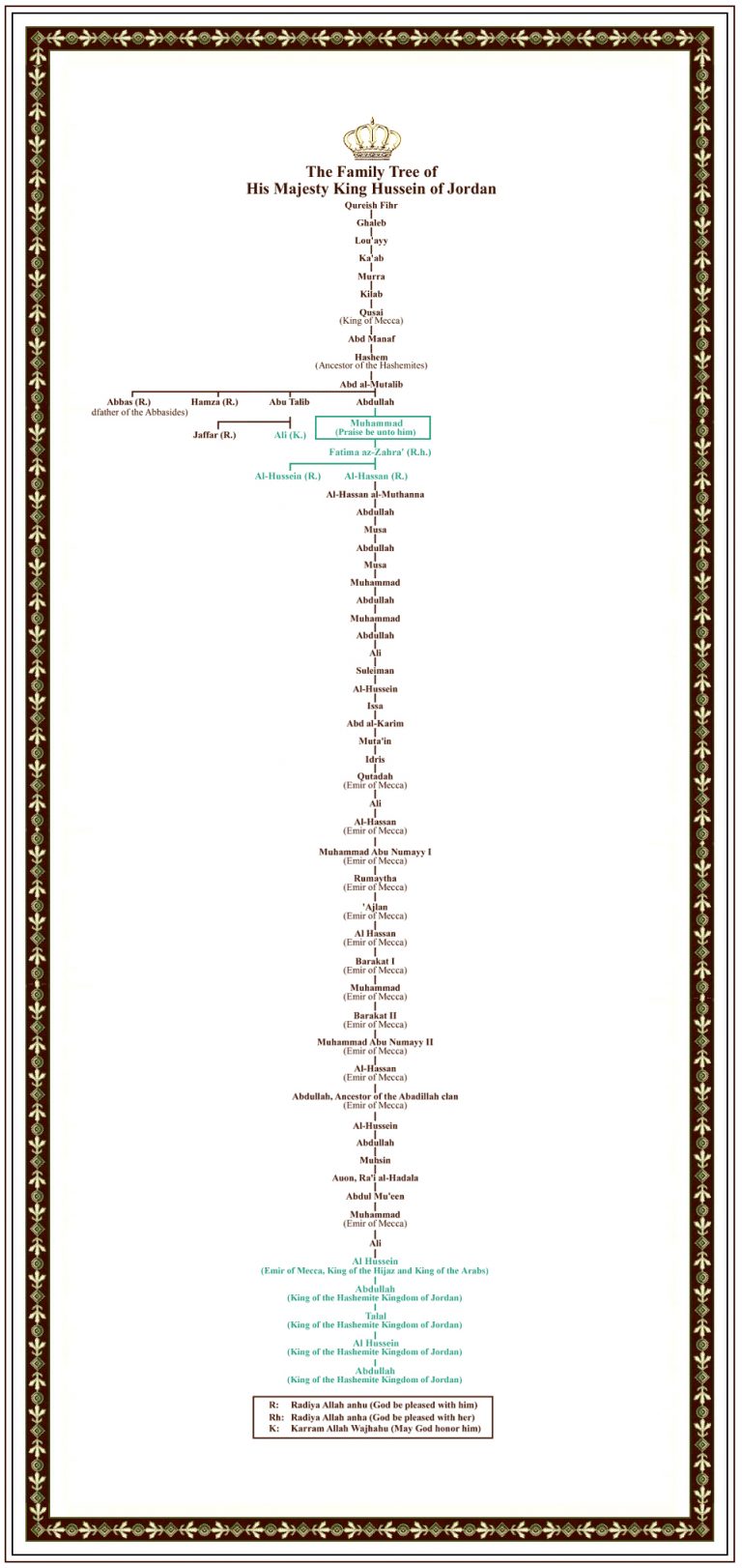

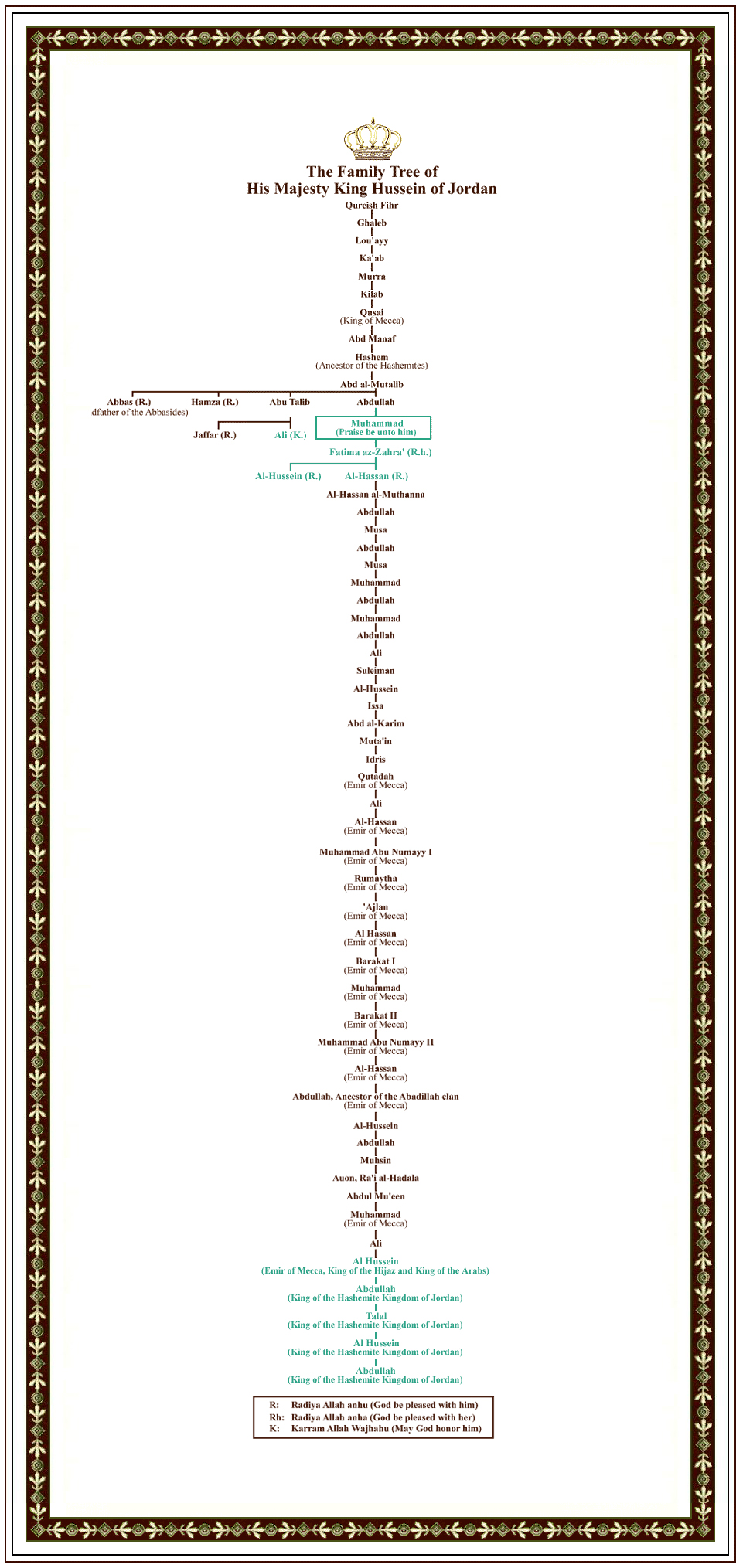

Bureaucratically certified genealogy of the modern kings of Jordan who claim Sayyid status.

Source

Bureaucratically certified genealogy of the modern kings of Jordan who claim Sayyid status.

SOURCE

https://www.alhussein.jo/en/family-tree

Composed circa 900 CE, Muhammad b. al-Hasan as-Saffar’s work Basa’ir ad-darajat is one of the earliest collections to provide a systematic explanation for the Imams’ significance. The author was a direct disciple of the eleventh Imam and has been regarded as an important authority by Twelver Shi’is for more than a millennium. In a chapter concerned with the special nature of the Imams’ bodies, he provides the following tradition from Ja’far as-Sadiq, reporting based on a chain going back to his grandfather, the fourth Imam ‘Ali Zayn al-’Abidin (d. 713):

God sent Gabriel to paradise, from where he brought Him back a type of clay. And He sent the angel of death to the earth, who brought back a type of clay from there. He mixed the two clays and then divided [the result] into two. He made us from the better of the two parts and He made our partisans (shi’a) from our clay too. Whatever our partisans incline to in the vein of ugly acts is due to the mixture of the wicked [earthly] clay. Their destination is [still] paradise. [In contrast] whatever our enemies possess pertaining to piety, prayer, fasting, and good deeds, that is due to the mixing of our good [paradisiacal] clay. Their destination is [still] the fire [of hell] (Saffar, Basa’ir ad-darajat, 47–48 [hadith no. 10]).

This cosmological explanation presents genealogy as a matter going not to descent by birth, as we might assume, but to the constitution of bodies. The Imams’ bodies were formed of a special substance that became apparent in the world through their birth one after the other. Those who support them, their partisans (shi’a), are then kin for them on the principle that their bodies were also formed of the same substance. Kinship in this instance is a matter not of consanguinity but original constitution whose guarantee comes from how the bodies come to act during their careers in the world.

Further, those who oppose the Imams are condemned irrespective of any good acts they might perform. Their enmity toward the Imams reveals their prehistorical constitution, trapping them in predestination. However, if they were to accept the Imams, then their prehistory would be corrected automatically. In this situation the present and the future create different deep pasts before their own materialization.

In traditions presented in as-Saffar’s Basa’ir ad-darajat, the Imams’ authority rests equally on their special knowledge. Such knowledge is subdivided into three categories, as in this statement from Ja’far as-Sadiq given when someone asks him to explain the enigmatic term jafr:

He replied, “It [jafr] is a bull’s hide filled with knowledge.” So then he asked, “What is al-jami’a?” He said, “That is a written record, the length of seventy forearm measures, on parchment of size like the thighs of a two-humped camel. It contains all that people need; there is no event needing a judgment that is not in it, to the point of [indemnity required for] a nail scratch.” He said to him, “What about the Book of Fatima?” He went quiet for a long time and then said, “You are discussing [such] things that some you need and others you do not. Fatima lived for seventy-five days after the [death of the] Messenger of God, peace be on him and his descendants. She was overcome with severe grief for her father. Gabriel came to her to relieve her sorrow for her father and to calm her soul. He brought news to her from her father—his location—and informed her of what would happen to her progeny after her. ‘Ali wrote all that down—that is the Book of Fatima” (Saffar, Basa’ir ad-darajat, 188 [hadith no. 6)].

The three concepts used to delineate the Imams’ knowledge here—jafr, jami’a, and Book of Fatima—differ based on their contents and implications. Jafr is indicated solely by its plentiful quantity, without an indication of what it consists of or provides. This is then a kind of secret or discretionary knowledge. Jami’a, in contrast, is similarly plentiful but is composed of what is needed to pass public judgment on matters pertaining to human behaviors and relations. Finally, the Book of Fatima is knowledge of the future, in both this world (since Fatima is informed about what would happen to her progeny) and life after death (Muhammad’s state and location). Between the three categories, the Imams’ multidimensional knowledge makes them masters of navigating the world in an extraordinary way.

Cosmological and epistemological explanations for the Imams’ status tell us that genealogy is never a simple matter of authority passing from one generation to the next. While the genealogical principle can be seen being deployed in many situations, the explanation for its efficacy can vary greatly between contexts. Genealogical distinction flows from the way the relevant bodies are constituted as well as what is transmitted through the chain that connects them.

As seen in the case of Imams and sayyids, one further implication pertains to gender. The ultimate root of sayyid status are Muhammad and Fatima, although ‘Ali, rather than the Prophet’s daughter, is the first Imam. The genealogy then continues with one Imam after the other, without including the nine other women who gave birth to the links in the chain (i.e., the mother of ‘Ali and all the Imams other than Hasan and Husayn).

From a social perspective, the absence of women, whose uninscribed presence makes the genealogy possible at all, highlights the “imagined” nature of lineage as a form of organizing time. Charts containing male names only that we can find throughout presentations of Islamic history based on timelines are androcentric ideological fabrications rather than obvious representations of social reproduction processes.

In the field of sayyid affiliation beyond the Imams, women do count as transmitters of religious authority rooted in the triumvirate of Muhammad, Fatima, and Ali. However, this usually happens only when they are descended from the imagined family rather than marrying into it. Sayyid women also act as a kind of boundary of the status since their marrying nonsayyid men is a matter discussed extensively in social as well as legal contexts. Although women’s names are often missing in formal genealogical tables in patrilineal situations, control over their bodies’ procreative potential is critical to the underlying system’s functioning.