Mothers of the night of ‘Ashur were saying out aloud:

Desert of Karbala, we will make you flourish.

We will sacrifice all our joys for the sake of your happiness.

Desert of Karbala, we will make you flourish.

Do not grieve, tomorrow morning your desire will be fulfilled.

Gladly, we will give you our children’s blood.

We will pray that you remain verdant until Resurrection.

Desert of Karbala, we will make you flourish.

But it is true that we will ask you this, again and again:

What mistake did we make, what was our fault?

Why this tribulation came on those helpless like us?

Tonight, see our devotion to acts of worship:

See the children’s passion for martyrdom,

Dressing up to sacrifice for the leader’s aim.

Desert of Karbala, we will make you flourish.

Our infants will put their lives on the line,

But they will not ask the oppressor for water.

How sure are their brave hearts ready to die.

Desert of Karbala, we will make you flourish.

We will bathe in blood head to foot,

But we cannot bend our heads in front of oppression.

We are teachers to daredevils ready to die,

Desert of Karbala, we will make you flourish.

The hands of Qasim, Muhammad, or ‘Ali Asghar,

The hand of [‘Ali] Akbar—none would undertake the oath.

This much we do trust our milk, by God.

Desert of Karbala, we will make you flourish.

Arrows, swords, and axes cannot frighten us.

Daggers, swords, and maces cannot make us bend.

The decision we had to make we have done.

Desert of Karbala, we will make you flourish.

On the mothers of Karbala, may your life be sacrificed, Asif.

By God, none among those mothers was a coward, Hashim.

Every moment they were fulfilling their duty saying:

Desert of Karbala, we will make you flourish.

Among a huge variety of available elegies on Husayn, I have picked this one as an illustration because the imagery contains a complex play on time. The first point of note is the personalization of both time and space: the speakers are identified as the mothers of a moment in time (the night of ‘Ashura), and the addressee is a space (the dessert of Karbala). In the speech, custodians of a critical moment in time indicate that this space desire’s sacrificial blood that will turn it from a barren dessert to a verdant landscape. While protesting unfairness, the mothers say that they will fulfill space’s desire through the sacrifice their beloved children are ready to undertake for the cause of justice.

Human beings who appear in the narrative—the mothers, their named and unnamed children, Husayn as the leader, oppressive enemies who wield weapons—create meaningful time and space through their actions. What they choose to do, acting righteously or oppressively, is the measure of time as well as space. ‘Ashura is a special time because of what some people did on the day years ago. The spilling of blood from their bodies on the ground made an empty desert flourish, the material flow imprinting the moment on the ground and rendering it a place marked into the future.

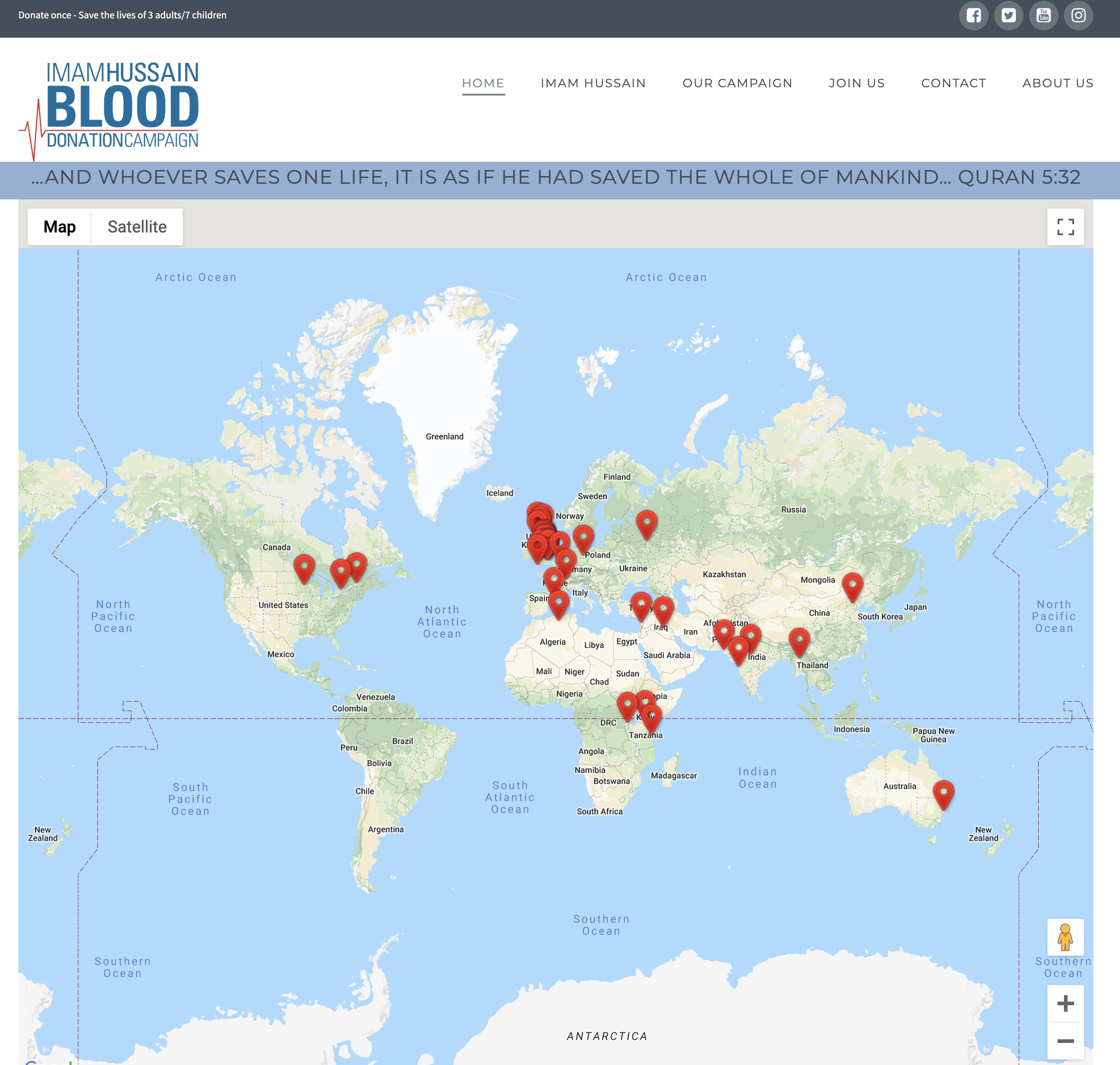

The poem ends by shifting the scene from the fateful night in the year 680 CE to the names of the poet and the performers (Asif [Bijnori] and Hashim Sisters). These signatures are a generic feature in many forms of Urdu poetry. Here they create the effect of making the present speakers a part of the story. To remain potent, the time of ‘Ashura and the space of Karbala require proclamation, commemoration, and reenactment, as happens every year in Muharram throughout the world.