Prophet Muhammad in Moving Images

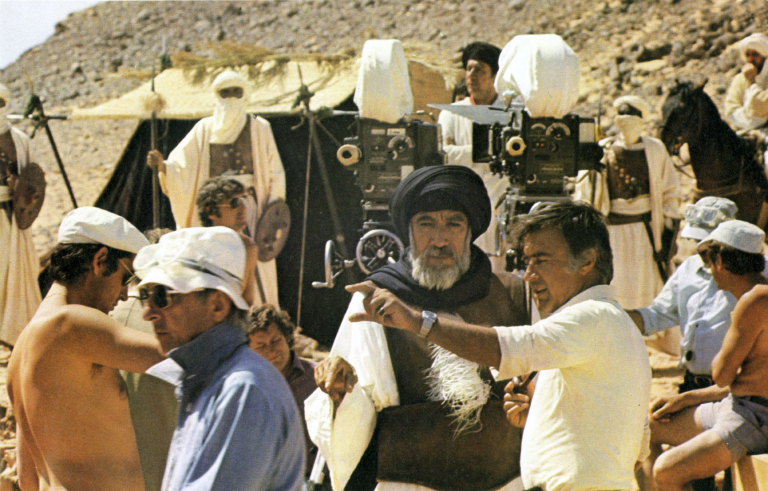

As a mediatic form, the moving image provides especially effective tools to rearrange passages of time. The amount of media produced along these lines in Islamic societies is stupendous and should put to rest any notion that Islamic expression is lacking when it comes to deploying the human body or other forms. When it has mattered, the antipathy toward images has had to do with representing a very small group of people, including the Prophet and some of his companions. As in the case of The Message, even for such cases, the restriction on the representation of some bodies has been generative with respect to complicating how we imagine the relationship between image and viewer.

To extend this topic, I would like to present the case of a reality show on Saudi Arabian television that is focused on the Prophet Muhammad. Entitled Law kana baynana (What if He Were among Us), this show ran for two seasons in 2007–2008 and is now available on YouTube. Its premise is to consider how one should live if one could be guided by the Prophet’s physical presence in the world today. In the opening to each episode, we are shown a series of vignettes alternating between the same actions occurring in staged ancient past and a modern city, often emphasizing nuclear families. For example, a kitten is saved from being trampled by a horse in the ancient setting, while the same happens with respect to a car on a modern city street. The show’s signature tune is a song in praise of the Prophet with the first verse “what if the beloved were among us.”

Law kana baynana, season 2, episode 10 (2008).

Each episode presents anywhere between one and four topics with the host, Ahmad al-Shughairi, providing information, giving advice, conducting interviews, and talking to people after capturing them in candid camera-like situations. The topics range widely, from broad concerns, such as the imperative toward mercy and knowledge, to ills that inconvenience people today, like double parking and letting taps run when not in use. Through all that is covered, the host keeps asking himself, his guests, and the audience about how to bring the Prophet’s opinions about daily life to bear on today’s social and individual concerns.

What may seem like a trite formula in this show is a sophisticated discourse aimed at collapsing the temporal extension between the past and the present in a sophisticated way. In modern, mediatized form, the show accomplishes the same task that Muslim scholarly classes have undertaken for centuries by emphasizing the importance of preserving the Prophet’s sayings (known as hadith) through attaching chains of human transmitters to texts and then using these to argue for proper ways to act. The key is that the Prophet is ever-relevant for all concerns, no matter how big or small. Feeling his presence requires cultivating knowledge of his acts that transmit instructions to the present despite having occurred in times long past.

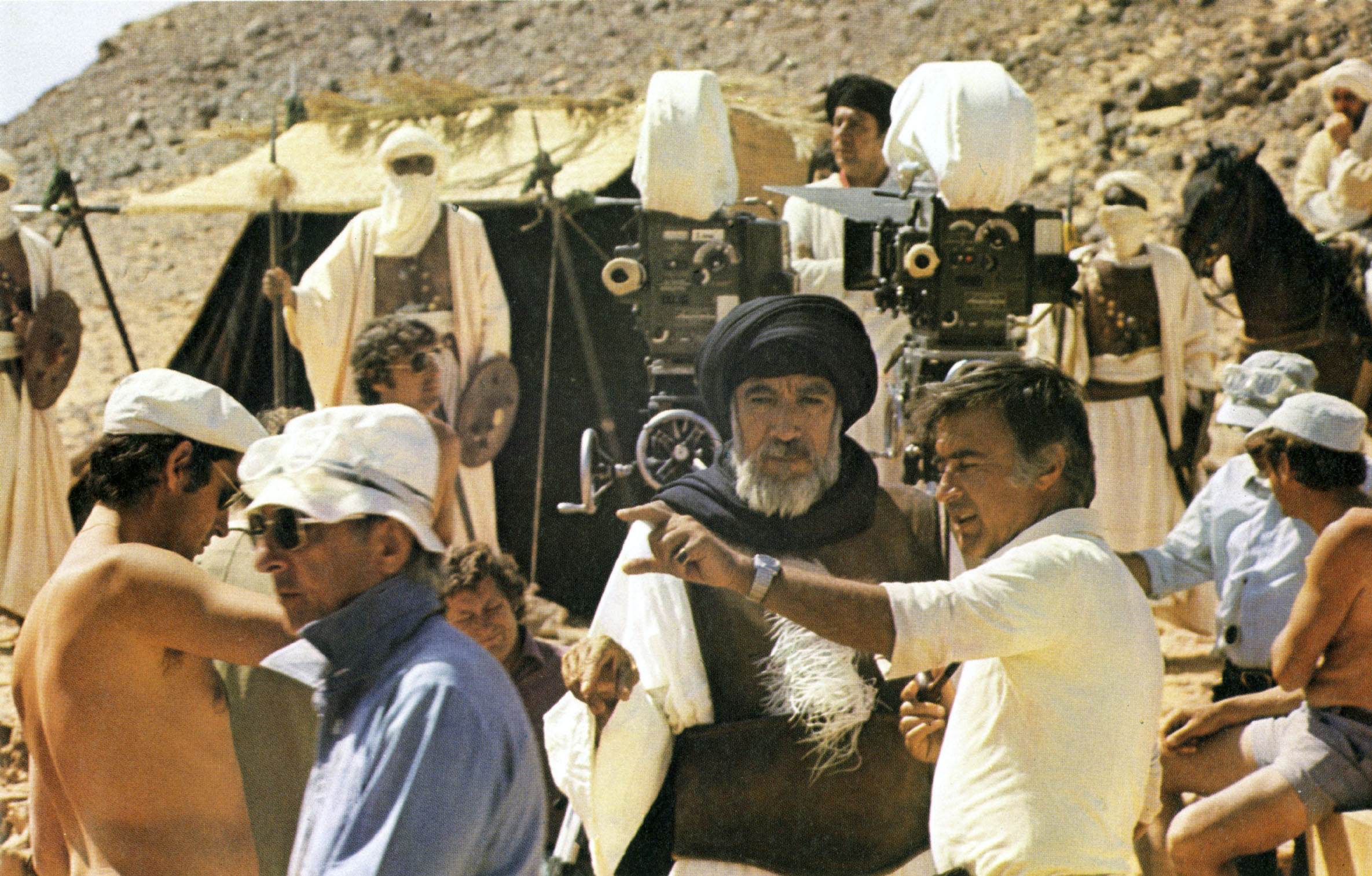

Peter Sanders, The Enwrapped One. “O you enwrapped in a cloak, stay up at night, except a little, half of it, a little less or a little more, and recite the Quran distinctly” (Qur’an 73: 1–4).

Source

Peter Sanders, The Enwrapped One. “O you enwrapped in a cloak, stay up at night, except a little, half of it, a little less or a little more, and recite the Quran distinctly” (Qur’an 73: 1–4).

SOURCE

The photograph was take on a visit to Prophet Hud, peace be upon him, at Wadi Hadramawt, South Yemen. © Peter Sanders Photography Limited

To convey a concrete sense for the program’s method, I will go through the contents of a seventeen-minute episode that was broadcast in 2008. Concentrating on “public places,” the first section of this episode consists of Shughairi interviewing a woman identified as Ms. Nur in a supermarket. She describes herself as the head of a women’s-only association called “Prophet Muhammad, You are Always in My Heart.” The organization aims to create a constant awareness of the Prophet through selling merchandise like t-shirts and stickers with its name (which includes the Prophet’s name) and other slogans.

At one point, Shughairi asks her, “If you had the chance to meet the Prophet, what would you do?” She tears up and responds, “I would kiss his feet.” The emotion then transfers to the questioner, as his eyes well up too and he talks about the Prophet’s quality of forgiveness. The two people in the scene register the Prophet’s presence in their lives through both words and emotions while also affirming that a hypothetical real meeting with him is impossible and would likely be overwhelming.

In the episode’s second section, Shughairi interviews Peter Sanders, a British photographer who became Muslim in the 1970s and has dedicated his life to documenting Muslim lives around the world. When asked what he would say to young Muslims, he responds by quoting an old statement that life is but a moment and should be lived with an attention that matches its preciousness. Given Sanders’s profession, the moment seems to refer to the split second in which a camera shutter captures an image.

Shughairi asks Sanders what he would tell the Prophet if he were present in the contemporary world. His response is that he would just sit in his company and look at him. He says too that whenever he is in Jeddah, he makes a point of going to Medina even for a couple of hours. Knowing that the Prophet lived there has endowed the place with a special aura that is not available anywhere else.

In the episode’s third section, Shughairi reminds people that the Prophet gave proper names to all physical things he used during his life. For example, he named his mule Duldul, the plate from which he ate was Gharra’, his satchel was named Kafur, and so on. This practice was an aspect of his mercy for all beings, animate and inanimate, and indicated a quality that should be cultivated by all Muslims. The program’s final section is a short comment on a book that lays out the Prophet’s political theory. Shughairi ends by saying that what is described in this book is a guide for political conduct in the twenty-first century.

Quranpark

Visitors inside the Cave of Miracles, part of Dubai’s Quranic Park in Dubai, UAE.

SOURCE

REUTERS / Satish Kumar, Alamy Stock Photo 2CKMRXN

Visitors walking across the parted waters of a lake at Dubai’s Quranic Park in Dubai, UAE.

SOURCE

REUTERS / Satish Kumar, Alamy Stock Photo 2CMA8RY (April 6, 2019)

Go to next slide

Go to next slide

This brief description of a short media piece should make clear that Muslims’ avoidance of Muhammad’s images does not indicate a lack of intimacy with the Prophet’s bodily presence. In fact, the very opposite seems to be true since proximity to him is available dispersed through the phenomenal world. People readily imagine themselves kissing his feet and sitting in his shadow. Places where he had lived and the names of objects he would have touched are like relics conveying his presence centuries later.

Matching the effect of The Message, people’s conversation in the reality TV program project the Prophet as a viewer who cannot be seen but has eyes that look upon the world. The spectacle to be viewed is not an image of his body but the world that is shared across eyes past and present. Within the experience of the world, the Prophet’s lifetime was a special temporality whose universal implications continue to be mined through verbal and imagistic means without the necessity of representing his form.