Theology of Time

Between June 4 and October 29, 1972, Elijah Muhammad gave twenty-one speeches at the Nation of Islam’s Chicago Temple #2 that touched upon all the movement’s major themes in its fully elaborated form. These speeches have been published under the title Theology of Time, a phrase that occurs in them often. The speeches do not constitute a straightforward ideological explanation that could be parsed analytically. These were extempore addresses presented to a live audience presumed to be familiar with what was being said. The collection does, nevertheless, illuminate why Elijah Muhammad saw the correct understanding of time to be the key to both religious salvation and sociopolitical and economic success.

In Elijah Muhammad’s account, the cosmos was born through a spatiotemporal autogenesis. In the beginning, there was nothing at all until an entity moved from one place to the next. This movement created time, that is, the measurable duration in which the movement happened. The movement that created time amounted to “the beginning of God. We had no beginning before He made Himself. We could not calculate on time, because there was no notion making time until after He made himself. He made a motion, and we’ve been reading Time ever since” (Muhammad, Theology of Time, 167).

The key corollary to this understanding is that God, whose proper name is Allah, is a material being. His very existence has to do with space and time. Moreover, all other beings who have come to exist since His self-substantiation are also material entities in their essence. They share the process through which Allah became existent and are further instantiations of His substance.

The original humans who came to exist were Black, with origins going as far back as seventy-three trillion years. The cosmos shared between Allah and Black human beings was subjected to a severe corruption 6,000 years ago, when a brilliant but rogue scientist, named Yakub, used manipulative miscegenation to make the White human race. This deformed, inherently violent, version of humanity then managed to take over the earth, suppressing the original Black people.

The enslavement and transport of Africans to the Americas, which deprived them of intellectual and material resources, was the apogee of the corrupt age begun 6,000 years ago. The crux of Elijah Muhammad’s message was to inform descendants of the enslaved, a “Lost” Nation now “Found,” about their true cosmological past:

You and I are created people, but the white man is not the created people; he is a made people. You and I have a long, long old birth record; it’s so long that we cannot tell you when we were born, but the white man, he is a man that our Scientists made here recently, 6,000 years ago. … There are two Gods. One made an evil man and the other one allowed a good man to remain. The evil man began 6,000 years ago, and the good man, we the Black people, have no birth record. … As God had taught me, in the Person of Master Fard Muhammad, to Whom praise due forever, that we were here millions of years before white folks came (365–366).

This statement provides further elements of the story of the cosmos. First, there is the important distinction between the “created” Black people and the “made” White people. The created are coextensive with the Allah of autogenesis, while the made ones are of recent, scientific manufacture, who are genetically programmed to be violent and unjust. To correct this situation in a manner that was preordained, Allah adopted a human form in the person of Master Fard Muhammad, Elijah Muhammad’s teacher. Fard Muhammad disappeared in 1934, after teaching Elijah Muhammad the truth. Together with being Allah in the flesh, he was seen as both the promised Second Coming of Jesus and the Muslim messianic figure named the Mahdi.

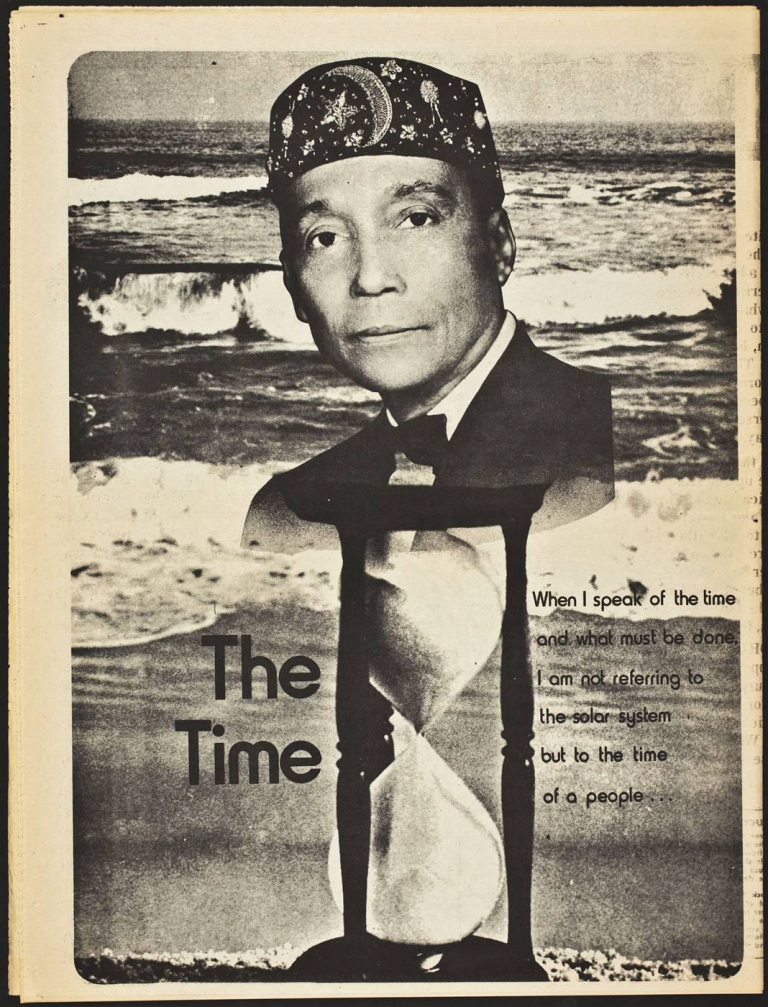

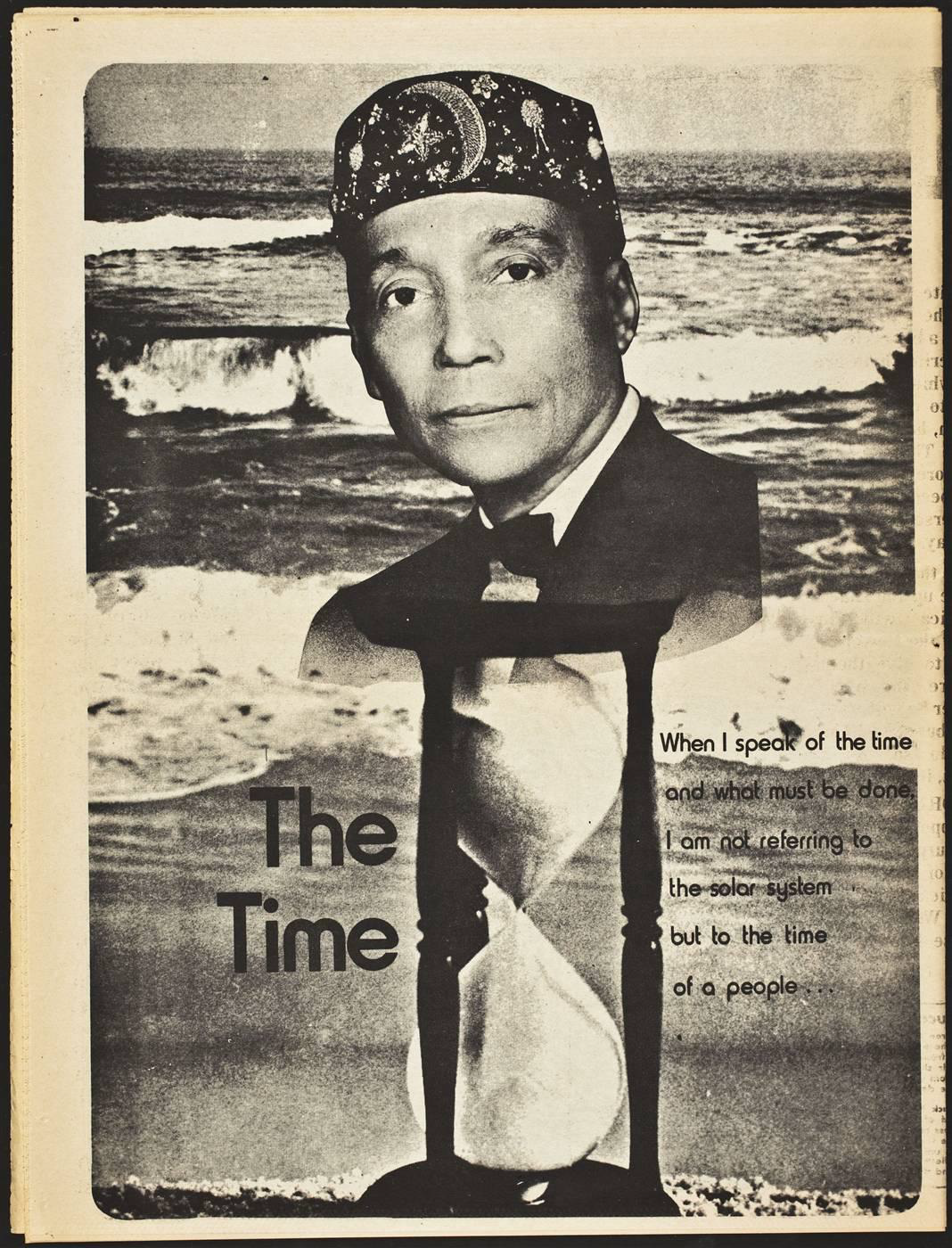

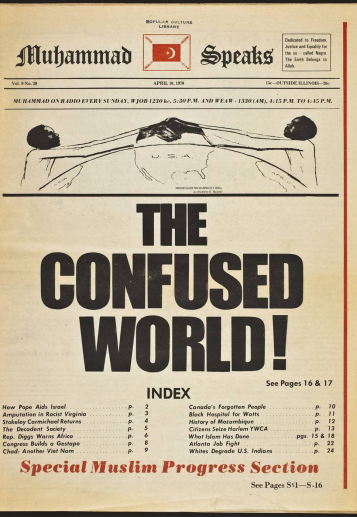

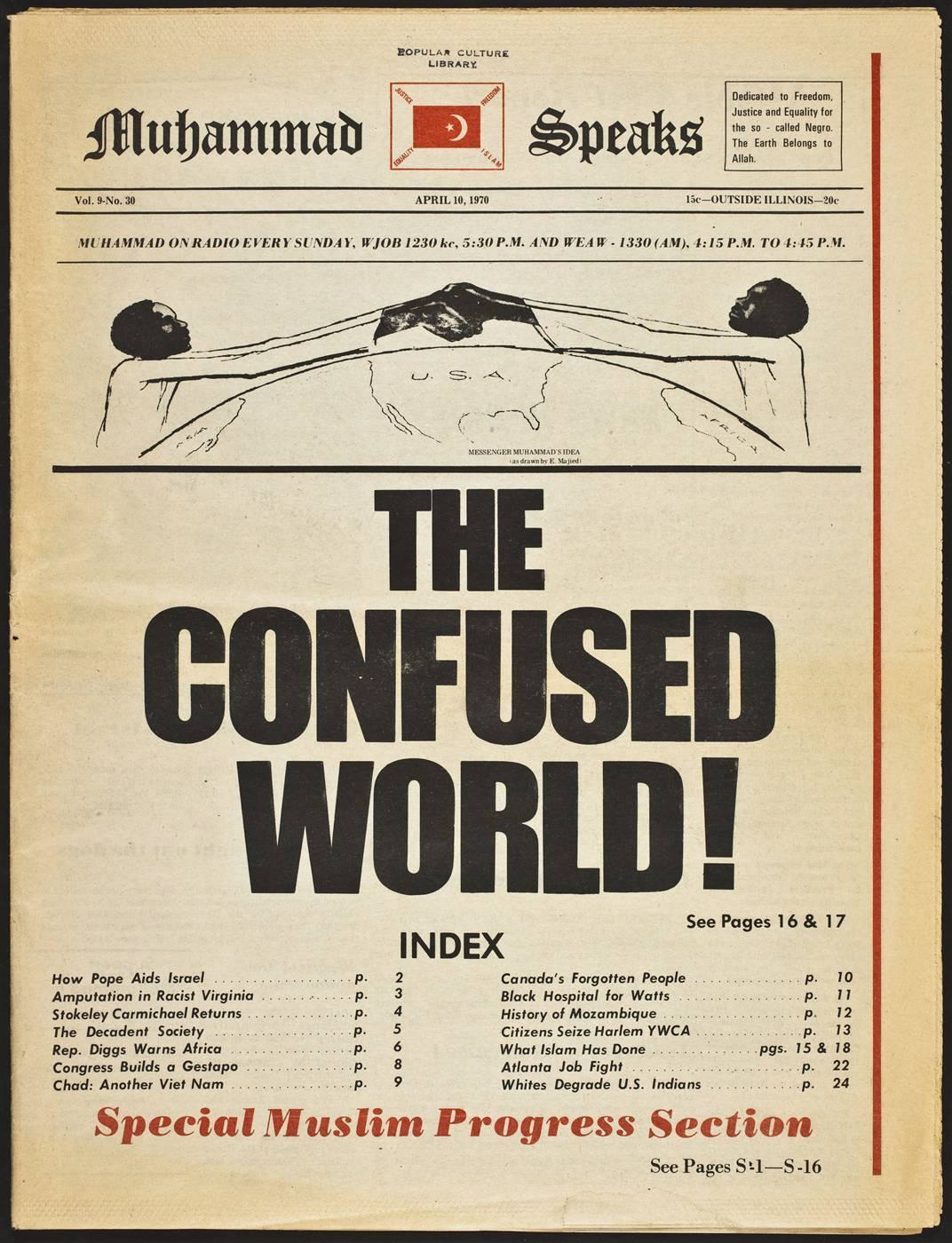

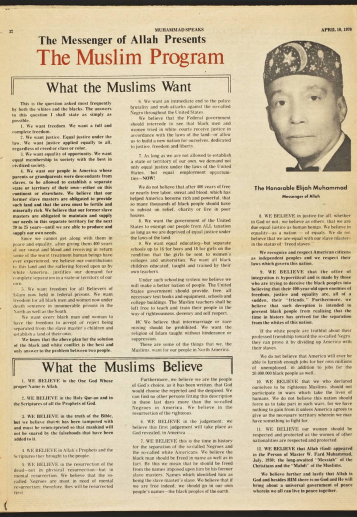

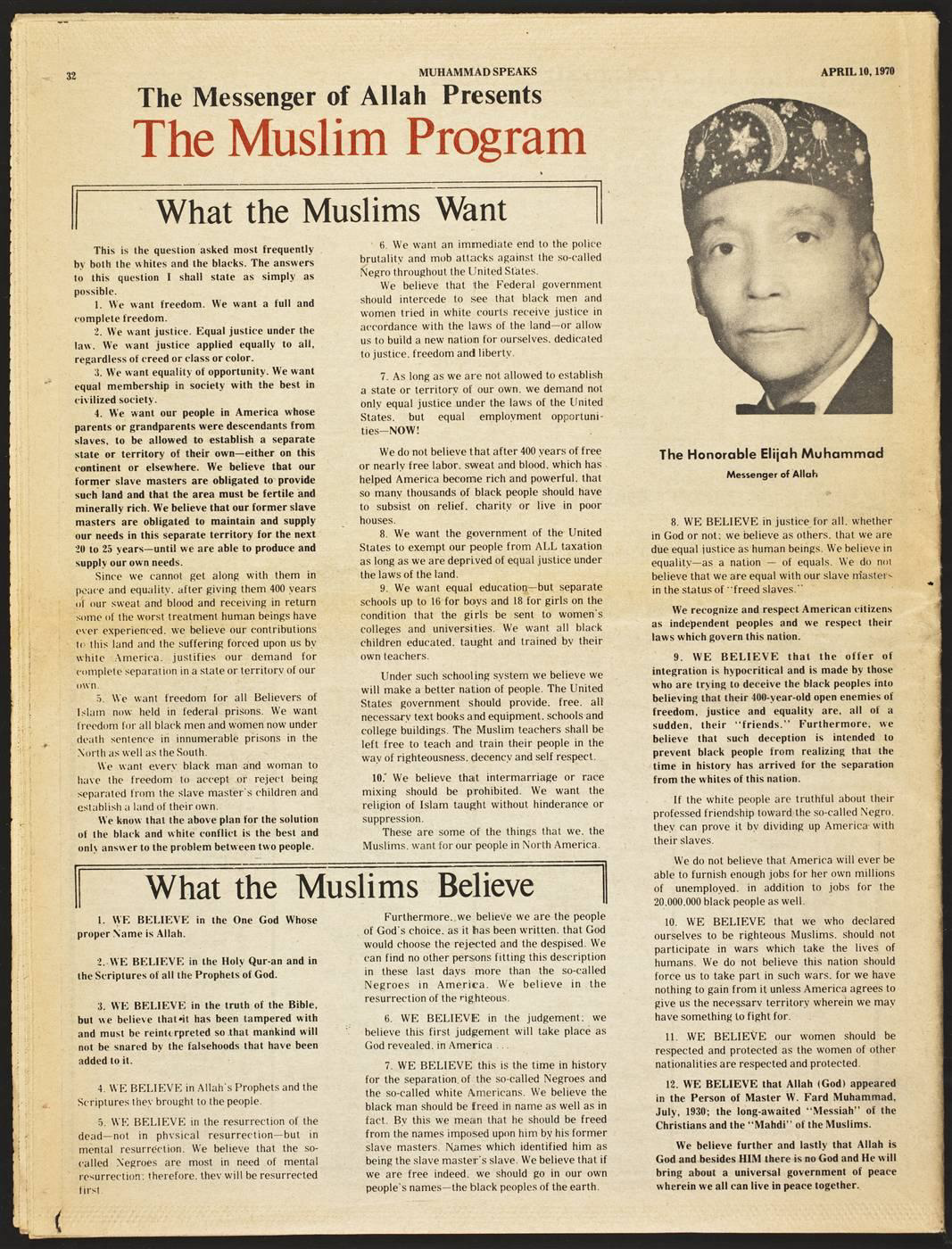

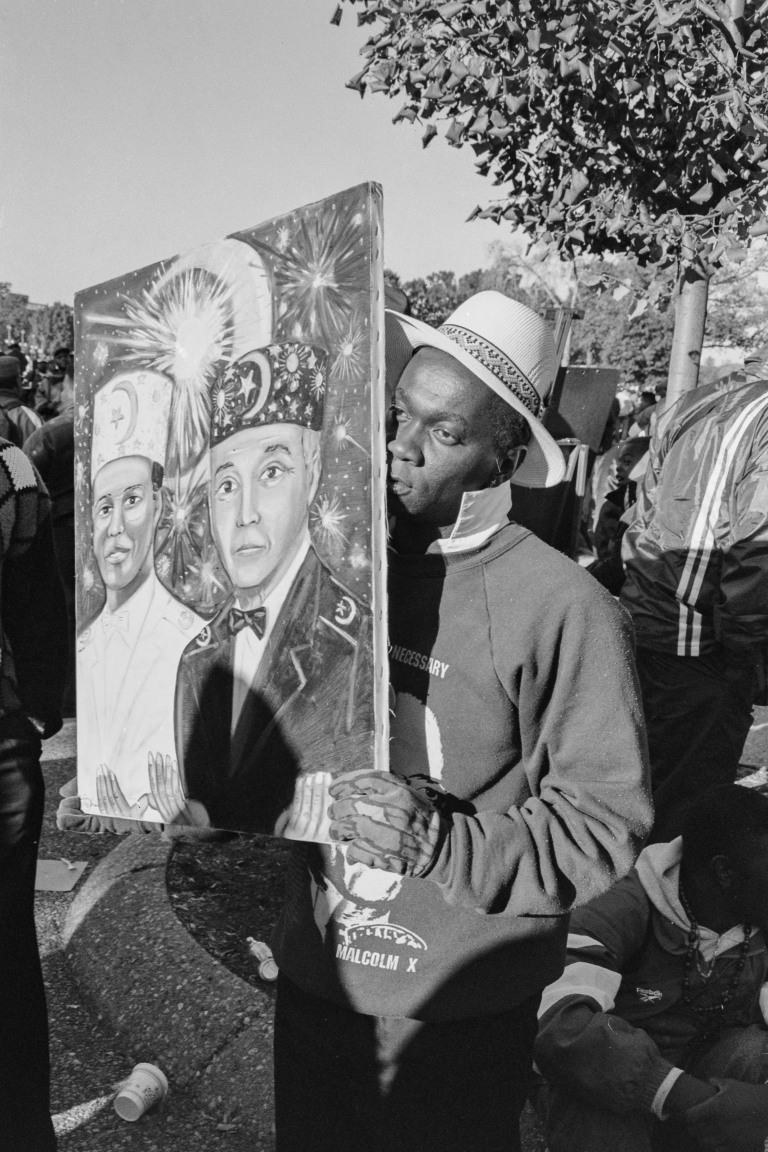

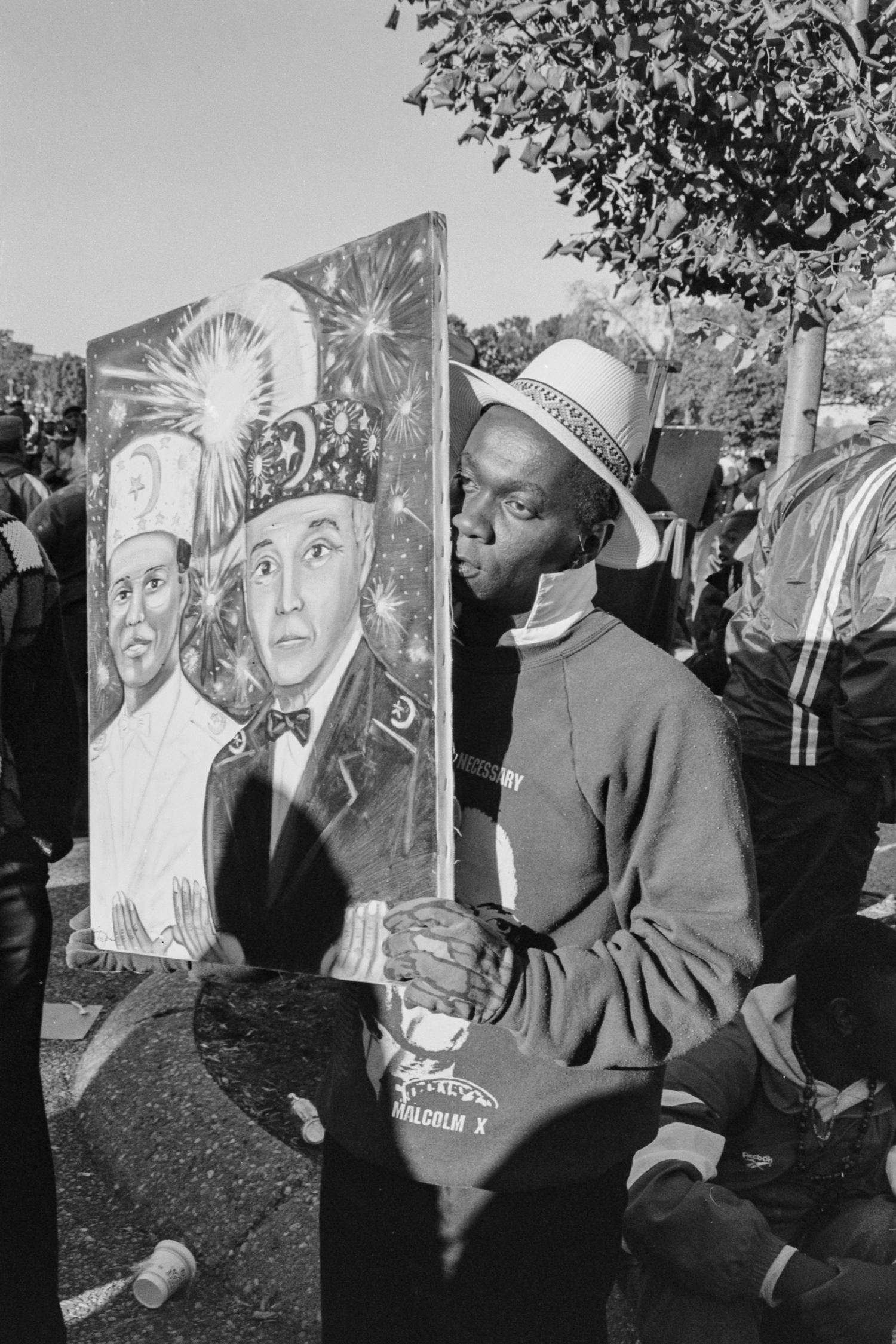

Back page of supplement to Muhammad Speaks, April 10, 1970.

Source

Back page of supplement to Muhammad Speaks, April 10, 1970.

SOURCE

Muhammad Speaks 9, no. 30 (1970), Supplement, JSTOR (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Elijah Muhammad saw himself as the Messenger of Allah, the student of Master Fard Muhammad, who learned the truth about the cosmos through an apprenticeship of four years and four months between 1930 and 1934 (115). The Nation of Islam was his project to teach other Black people the truth of their past, especially the essential difference between them and White people. This view included the idea that the Islam that was begun by Muhammad in Arabia was a part of the corrupt White interregnum that fell within the last 6,000 years. Now, that Islam was to be replaced by the Nation of Islam:

I am Elijah of your Bible, I am the Muhammad of your Holy Qur’an; not the Muhammad that was here 1,400 years ago. I am the one of whom the Holy Qur’an is referring. The Muhammad that was here 1,400 years ago was a white man, then they put up a sign of the real Muhammad. It’s there in Mecca, Arabia; they call it the little Black Stone. I looked at it. I made seven circuits around it. I kissed the little Black Stone, but I didn’t like kissing it, because I knew what it meant. It means that the people will bow to the real Blackman who is coming up out of an uneducated people, having not the knowledge of the Bible and Holy Qur’an, which is why they made it an un-hewed stone; he will be uneducated. So, I was there kissing the sign of myself and I was afraid to tell them that this is me you’re talking about here (3).

Predicted in the form of the Black Stone affixed to the wall of the Ka’ba in Mecca, the Messenger of Allah, Elijah Muhammad, arose from descendants of the enslaved in America to correct a cosmic corruption. By revealing the true nature of time, he disabused Black persons from “tricknology,” that is, the collection of knowledge and practices that have allowed White people to keep Black people subservient, with ever increasing sophistication, for the last 6,000 years through blocking access to knowledge of their own beings.

Elijah Muhammad’s Theology of Time was a subversion of tricknology. Its cardinal principle was that there is no other life than what is experienced in the here and now. The notion of an afterlife of the spirit after death was a subterfuge of tricknology meant to render Black people inert: “There is no man that dies and goes back to the earth, then returns again. That is the thing that just doesn’t happen” (21).

With the arrival of, first, Allah in the person of Master Fard Muhammad and, second, the Messenger, Elijah Muhammad, the world was at the cusp of a radical transformation. Now it was possible for Black people to break the cycle of delusion and corruption started 6,000 years ago. This was the moment of resurrection promised in scriptures such as the Quran and the Bible: “Time brings about all things. Time is making you manifest. They call it resurrection. To resurrect the dead it doesn’t mean resurrecting a physically dead person, but a mentally dead person. You must remember that for 400 years, we have been a mentally dead people” (221). Accepting Elijah Muhammad’s message and dedicating oneself to the program for the future he had charted out meant being resurrected out of ignorance into knowledge.