Escape to Eternity

Literary sources pertaining to Qutham b. ‘Abbas are scanty, and it is uncertain as to when, how, and why a man who might have died during a siege of Samarkand in 677 turned into the Living King. Aspects of the eventual legend (discussed below) correspond with stories of heroic figures in Buddhist, Manichean, and Islamic lore. Moreover, the story bears a close resemblance to the figure of the Shi’i Twelfth Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, who was born in the ninth century, went into occultation in 874 in Samarra, Iraq, and is expected to reappear at the end of time. Like Muhammad’s statement on Qutham quoted above, the Twelfth Imam is also supposed to look like the Prophet. It seems likely that Qutham’s identification as Shah-i Zinda came about through a coalescing of strands of ideas pertaining to expectations of long-lived holy persons. The composite then became especially meaningful for Islamic identities in Samarkand, a major Central Asian city, circa 950–1050 CE.

The contents of stories concerning Shah-i Zinda are more interesting than their indeterminable genealogy. A long narrative in a work entitled Qandiyya that is focused on the shrines of Samarkand is especially illuminating. The dating and authorship of this work are vague. The best we can guess, based on the language and style and the personages mentioned, is that it was composed circa 1450–1600, although the currently available recension dates to the early twentieth century. Whatever the time and reasons for transcription, we can be sure that the work presents Shah-i Zinda in the form that has mattered for socioreligious and political life in Samarkand for at least the past six hundred years.

The Qandiyya presents two stories containing competitions between kings. In both, Shah-i Zinda is one party, while in opposition are, in the first, a king named Zabur Shah placed in the seventh century and, in the second, the conqueror Tamerlane (d. 1405). The first story explains the shrine’s origins, while the second affirms its status seven centuries later in conjunction with describing how the physical setup facilitates the possibility of otherworldly journeys.

The work states that Qutham had arrived in Samarkand with an Arab/Muslim army and was appointed the new governor upon conquest. Zabur Shah was the defeated non-Muslim ruler, who began plotting to take the city back from Muslims. Seeking advice on how to accomplish this, he was accosted by Satan in the guise of an old man, who told him that the best thing would be to attack Muslims during the communal prayers during the Festival of Sacrifice. This would be efficient because all the city’s Muslims would be together and unarmed. Moreover, their concentration in prayer was such that they would not notice that enemies were present all around, dispersed in the crowd. Zabur agreed to the plan and it was executed, with special instructions to all that killing Qutham was essential since that would dispirit the Muslims. During the close range battle that followed, Qutham was surrounded by enemy soldiers, whom he could dispatch with ease until Zabur ordered that he be attacked from afar, using arrows. In this situation, Qutham beseeched God to come to his aid.

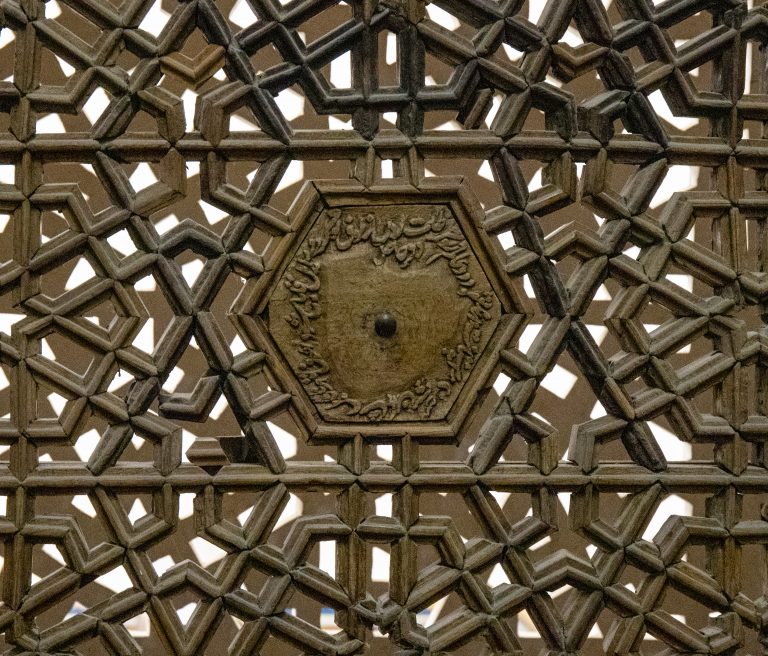

Central area at Shah-i Zinda.

Source

Central area at Shah-i Zinda.

SOURCE

Photo 122303682 © Sergey Dzyuba | Dreamstime.com

As Qutham’s appeal went out, a man appeared and told him to look at the ground. This was the legendary figure Khizr, an ever-living Prophet who is associated with water sources and the color green. Qutham saw that a well had opened where he was standing, into which he jumped based on Khizr indicating that that was God’s command. When Zabur Shah saw this happen, he ordered his soldiers to pile stones and garbage into the well so that Qutham would be killed. But unbeknownst to them, God had appointed an angel in the well with the job of taking whatever was being pelted and chucking it away to protect Qutham.

When the enemy looked into the well and did not see Qutham, Zabur asked for a volunteer and one man offered to go down to check. But as soon as he was lowered, he wanted to come back. He reported that he encountered a fire-breathing dragon down at the bottom, who would have incinerated him if he had not managed to get out immediately. From then onward, Qutham was supposed to be living down the well until the end of time, when Jesus would reappear in his Second Coming. He would then come out, rule for forty years, and then all would be destroyed in the world’s apocalyptic end (Anonymous, Qandiyya, 24–32).