A Brazilian Confession

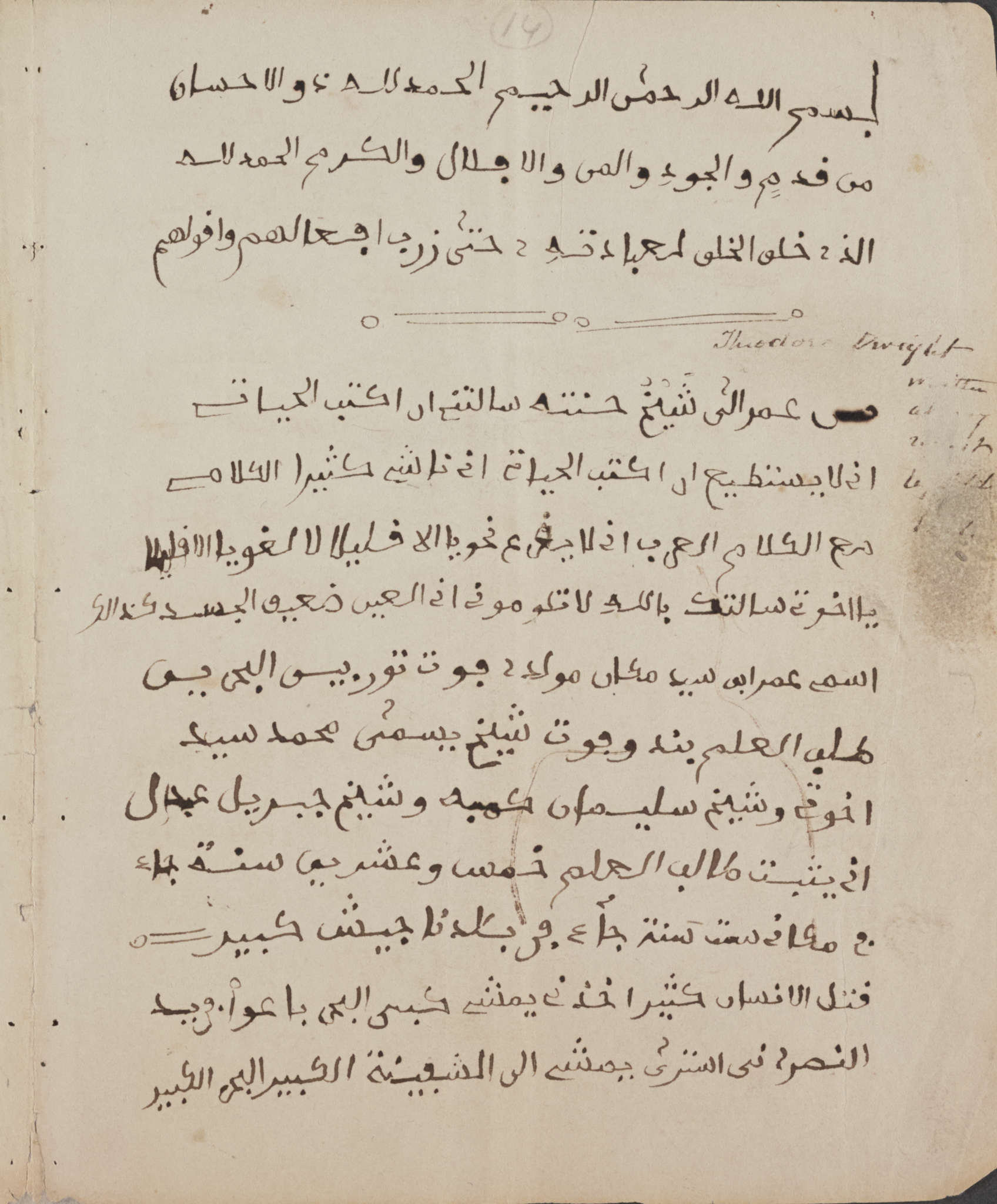

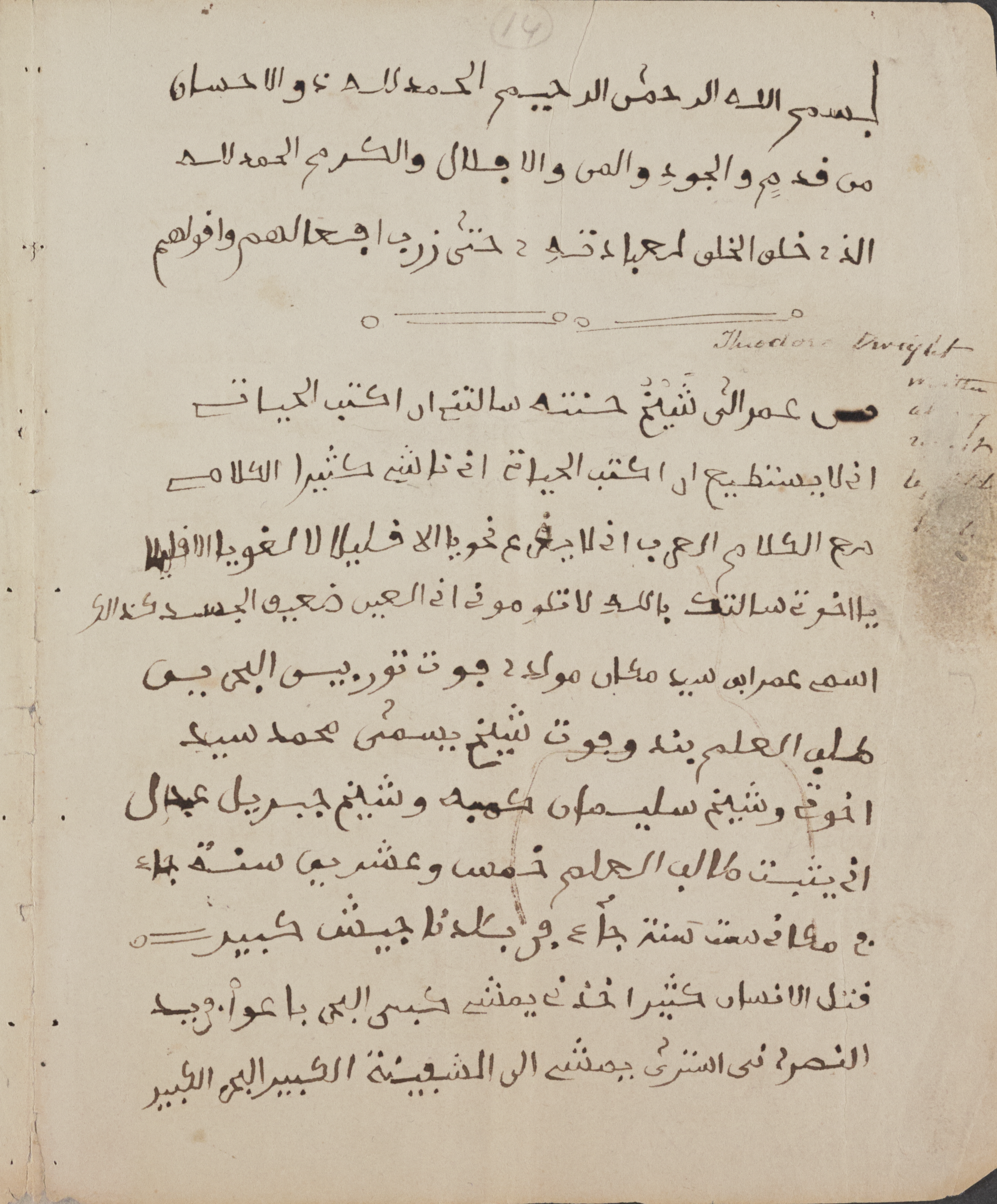

Possessing Arabic script texts can be dangerous business. The truth of this proposition was borne upon Rufino in Recife, Brazil, on September 2, 1853. Our sources of information for this story are a document in the government archive, which is accusatory as befits the genre, and newspaper reports, which vary between being sympathetic and hostile toward him. The city at the time was awash with apprehension regarding an insurrection by peoples of African origin. If such an event were to come to pass, it would have replicated earlier rebellions, most notably one in 1835. Then, enslaved Muslims, duly armed with Arabic script texts as well as weapons, had featured as central characters. In Recife, authorities had swooped in upon Rufino due to his reputation as an influential person in the community who, moreover, plied the healing trades using amulets and prayers of Islamic provenance. In the event, Rufino was released without charge within two weeks of arrest once the texts in his possession were deemed innocuous. It is likely, too, that his clientele included people influential enough to press for his release.

At the time of his arrest and release, Rufino was “the impecunious resident of a basement room in a Recife townhouse in Rua da Senzala Velha [Old Slave Quarters Street]. The other African suspects detained during the investigation that led to his arrest were also humble folk” (Reis, Gomes, and Carvalho, Story of Rufino, 241). However, his life as encapsulated in the account he gave to the interrogators paints a rich picture of the times he inhabited. Matching his details to other available documents, historians have placed him in larger patterns of the relationship between Africa and Brazil during the nineteenth century.

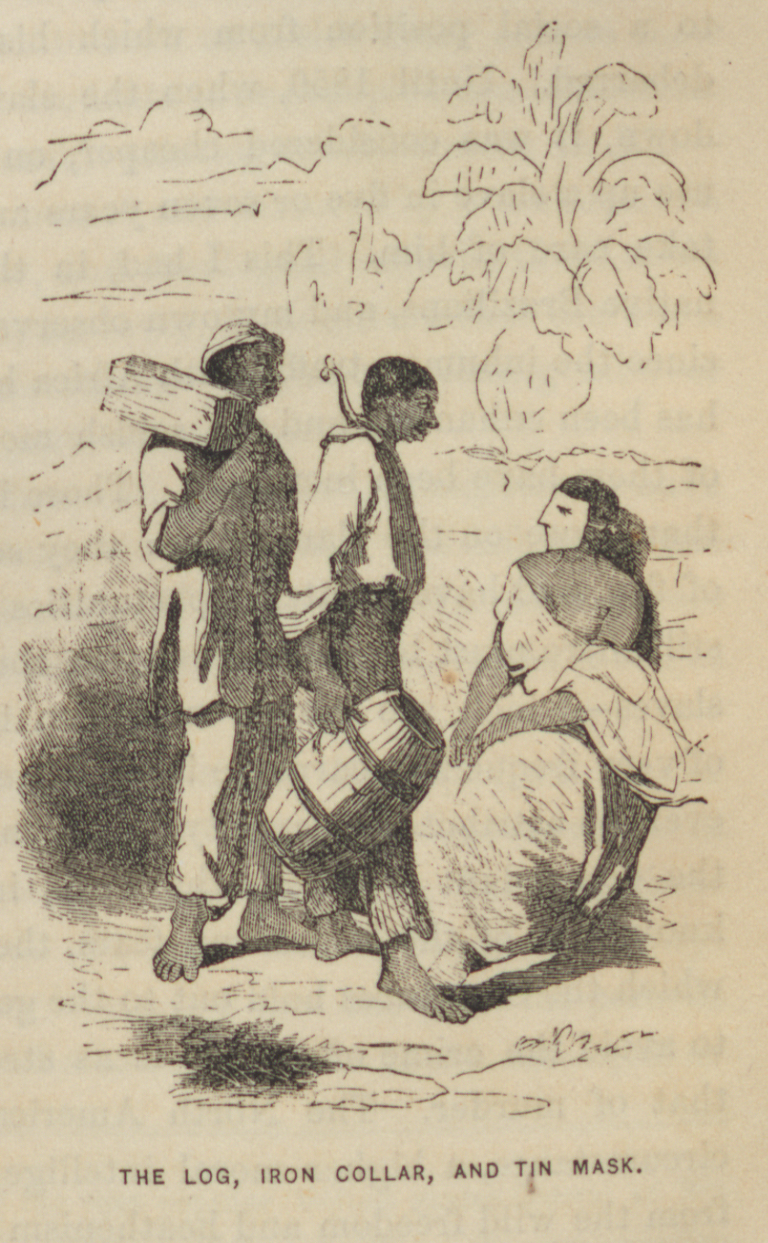

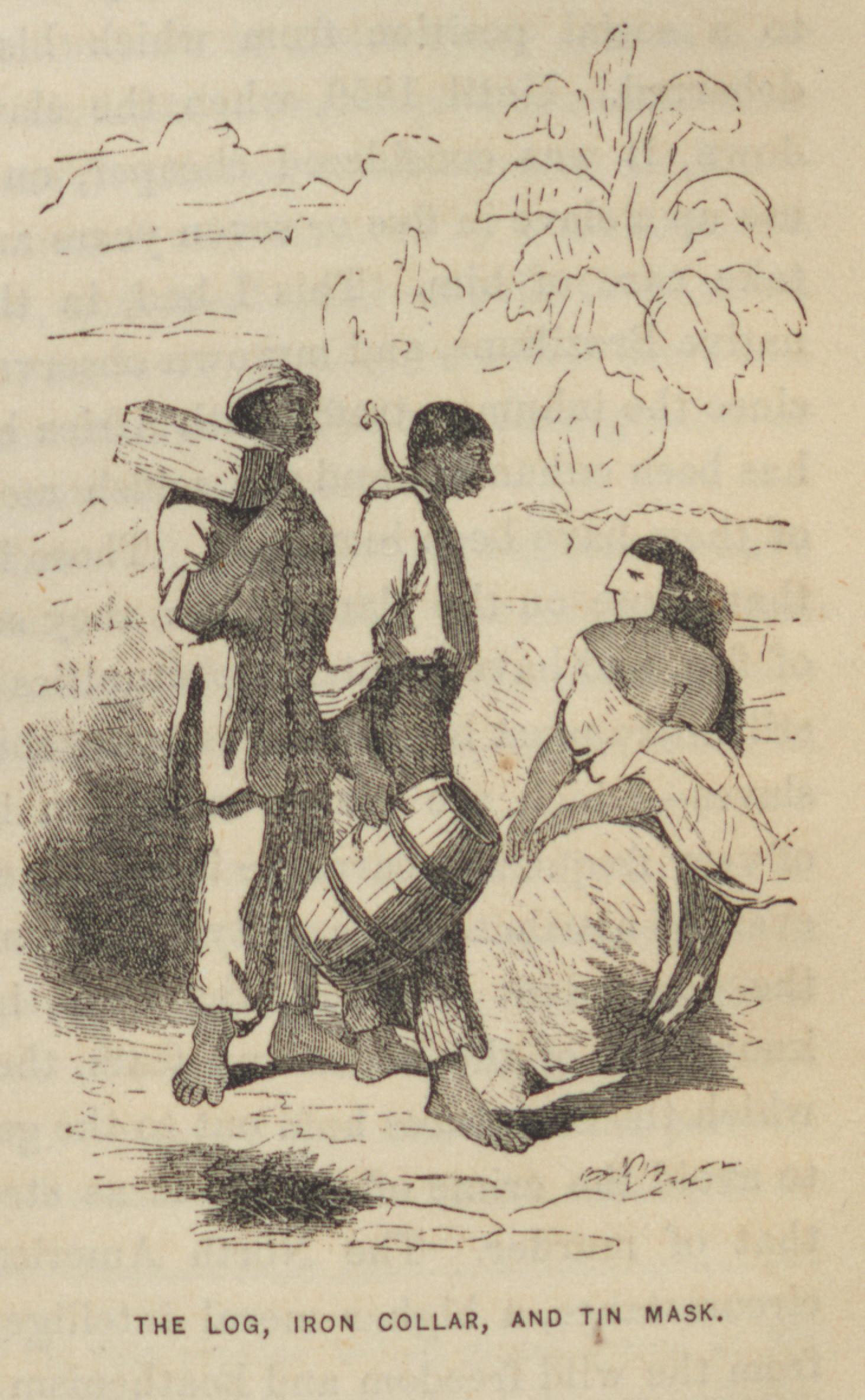

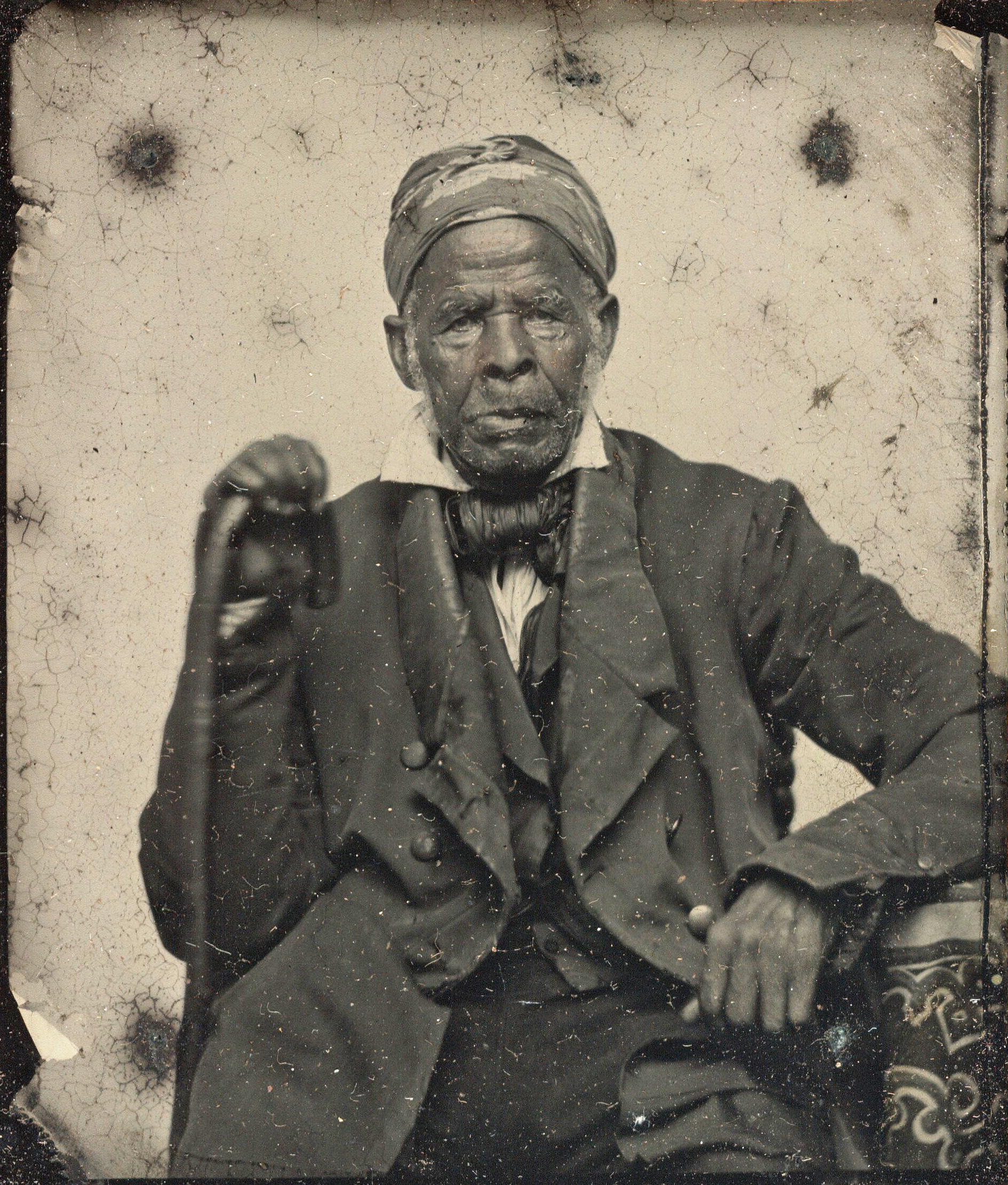

Methods for punishing enslaved Africans in Brazil.

Source

Methods for punishing enslaved Africans in Brazil.

SOURCE

D. P. Kidder and J. C. Fletcher, Brazil and the Brazilians Portrayed in Historical and Descriptive Sketches (Philadelphia: Childs and Peterson, 1857): 131

According to Rufino’s account, he was born in West Africa in a Muslim family, captured by a rival Muslim group during war, and sold to slavers transporting people to the Americas. He arrived in Salvador, a city in Bahia, at the age of seventeen around 1820 and was purchased by an apothecary who trained him to work as a cook. A large percentage of this city’s population was African at the time, including a substantial number of Muslims who would later feature in the rebellion of 1835.

After eight years in Salvador, he was sold to a merchant in Porto Alegre, and two years later he was auctioned in public when the merchant went bankrupt. Purchased by the local police chief, he was put out as labor for hire, a practice that allowed slaves to keep some of their earnings. He was then able to save enough to buy freedom from the third owner. The manumission document, dated to 1835, remained one of his crucial possessions through the rest of his life.

As a free man, Rufino moved to (or was possibly expelled to) Rio de Janeiro, where he eventually joined the slave trade by signing up as a cook. He then undertook multiple voyages across the Atlantic, on more than one ship, in which he worked on deck while also being a small investor in goods transported for trade. His choice of occupation was not unusual. Many freed Africans worked on slaving ships, where they faced less racial discrimination than on land and their knowledge of African languages and geography was an asset. The slave trade to Brazil in the relevant period occupied a legal gray zone. Its results were greatly in demand in Brazil, while slave ships faced opposition from the paramount European power, Great Britain, which had abolished slavery in 1833. Rufino was on the ship Ermelinda’s slaving voyage when it was captured and boarded by British forces on October 27, 1841. This resulted in Rufino being taken to Sierra Leone, a British colony, in December 1841.

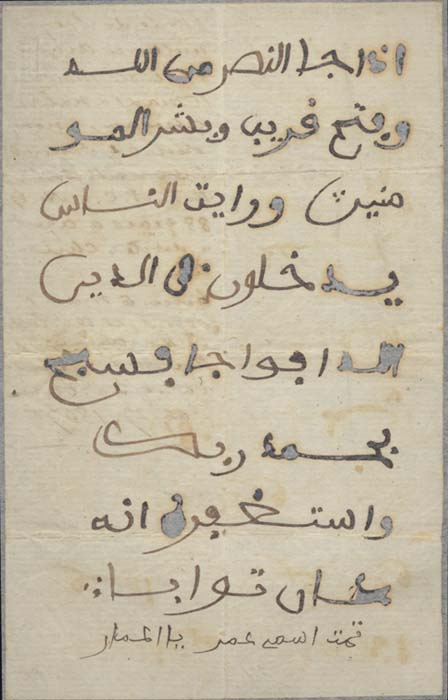

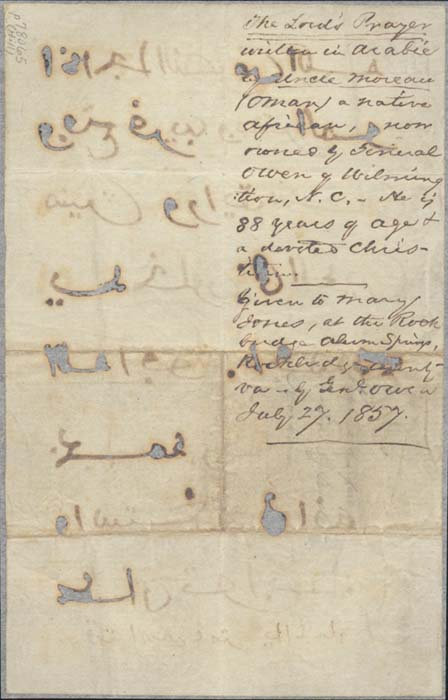

As a trial took place over many months pertaining to the Ermelinda (the case was eventually dismissed, for complicated reasons), Rufino got the opportunity to attend Islamic schools in Sierra Leone. Here he improved his knowledge of the Arabic script and Islamic religious materials, a process that was interrupted in his youth due to enslavement. He then returned to Brazil in the middle of the 1840s and settled in Recife, changing his occupation from an accomplice in the slave trade to religious healing and instruction. Between his local connections and the prestige and facility acquired in Sierra Leone, he was well placed for the job.

In Recife, he was known under the name Abuncare, which may have come from his childhood in a Muslim community in West Africa. He made a modest living as a healer and spell-maker, catering to Muslims and non-Muslims, Africans, and Whites, and possibly acted as a religious functionary in matters such as conducting marriages. Government officials’ knowledge of Rufino/Abuncare’s reputation led to the interrogation that bequeathed the documents we can now use to tell his story.

Rufino’s narrative has many more details that I have omitted for lack of space. The summary I have presented is useful to treat the story as a node, permeated by diverse and even contradictory forces, in history imagined as a web. Here Islam is marked by textuality and literacy, key elements that distinguished Muslims from non-Muslims among the enslaved in the Atlantic context. But whether as a force to be harnessed or as a threat needing neutralization, the texts signified through their forms, as writing, and not due to the discourses contained in them. They were understood as being powerful as objects and not for the semantic content of the language. We know from comparable materials that Rufino’s texts were likely parts of the Quran and other devotional or legal works in use in West Africa. Their meaningfulness in this context resided outside their linguistic content, in sociointellectual practices that originated in West Africa and stretched across the Atlantic via minds and bodies transplanted through the slave trade.

On the question of Islam’s relationship to slavery, Rufino’s story is equivocal. We see Muslims slaving and being enslaved, the main Muslim character transposing between these roles during his life. In the end, he seems to have used his Islamic affiliation and knowledge to acquire social status across religious boundaries. For matters of healing and fulfilling wishes, his clientele seems to have cared little about his confession. In the Brazilian world formed of colonization and slavery, Islam and its texts could be put to entrepreneurial use across religious, cultural, and racial formations. If Islam’s history is understood as its role in worlds made by human beings, Rufino’s story shows it to consist of ideas and practices transforming to meet circumstantial imperatives unconstrained by preexisting discursive specificity.