Islam can be a suffocating prison, a collection of outdated ideas and practices that underwrites the oppression of elites over common people, the old over the young, and men over women. Left unexamined for centuries, Islam in this instance equates to calcified communal habits. One feels that Islam is ripe for wholesale dismantling, to be replaced by either a better reconstructed version or an altogether different sociointellectual system. In this understanding, the progressive improvement of human ideas over time has made Islam obsolete and temporally regressive. Those who remain invested in it, such as religious scholars, are in danger of being left behind by the rest of the world. Muslims who insist on living by old Islamic patterns are then frozen in time, relics of the past with disorienting presents and dismal futures.

The view of Islam I have just described represents an opinion that features extensively in thought generated during the approximate period 1850–1950. This understanding was endemic to European colonial discourses, where it was useful to justify sociopolitical domination of Muslim-majority societies. Relatedly, and more significantly, this view was adopted extensively by people who identified as Muslims or came from Muslim backgrounds. Sometimes collectively called “modernists,” those who adopted the view were compelled by a sense of competition with Europeans, next to whom Muslims lagged in economic and political terms. In societies and polities big and small, we find influential speakers and authors asking Muslims to pay urgent attention to Islam’s backwardness.

In the sociopolitical arena, the greatest consequence of European imperialism was the imagining of new nations, many of which would eventually become the basis for new states upon colonialism’s end. In political formations where Islamic identification mattered, new histories that were posited as nations’ pasts accommodated Islam in a variety of ways. Sometimes, Islam was deemed essential to the nation, resulting eventually in “Islamic” republics, kingdoms, emirates, and so on, all claiming a privileged religious position. In other cases, Islam was acknowledged as a part of social but not political identity, which often required placing limitations on institutions and classes seen to represent Islam. Across the board, the nation and Islam as collections of ideas modulated to each other, imagined as long-standing aspects of individual and communal identity regenerated in response to the age of modern nation-states.

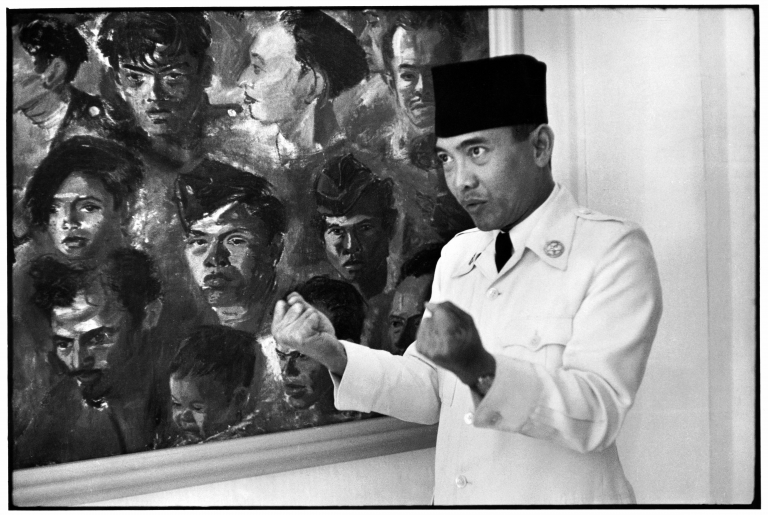

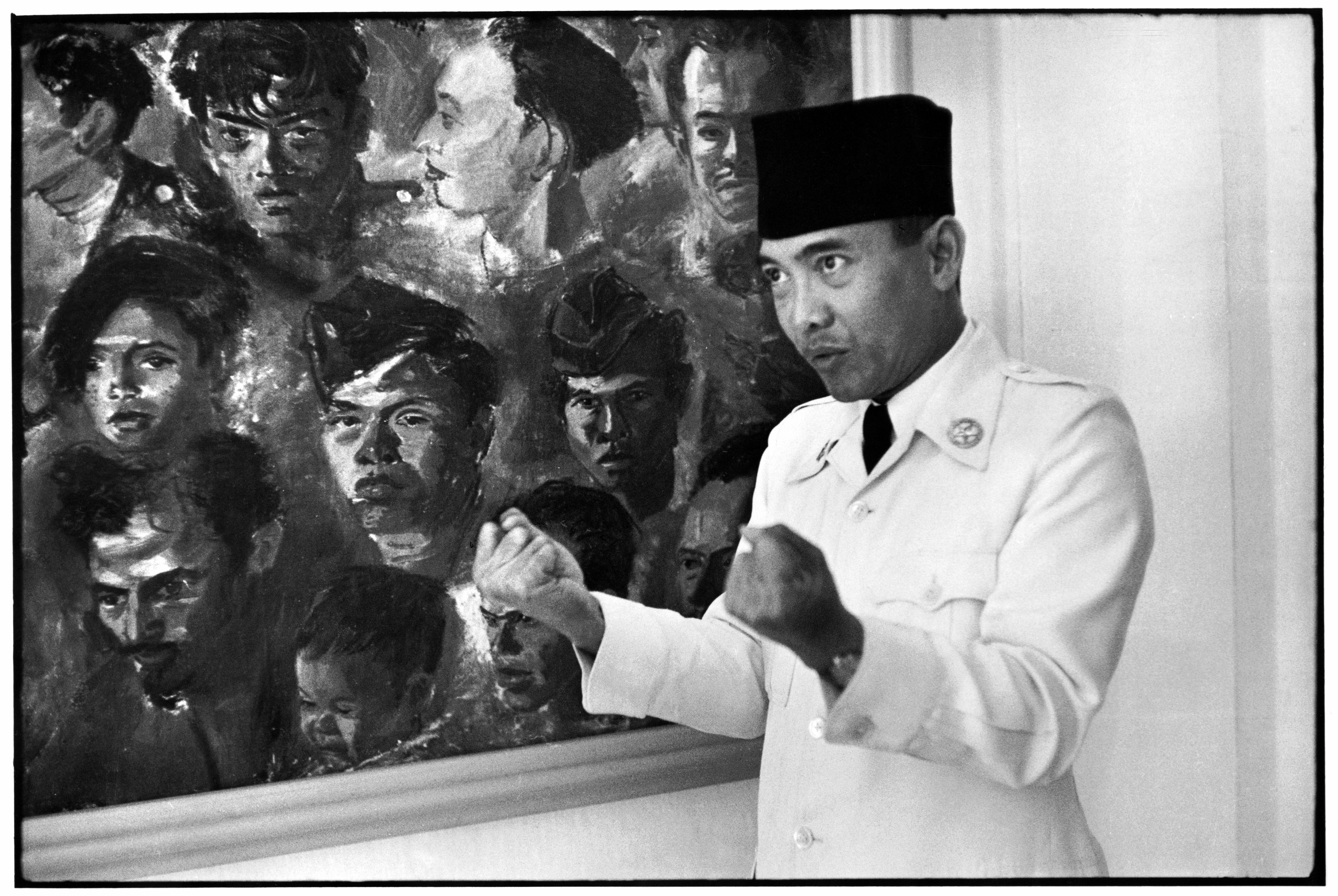

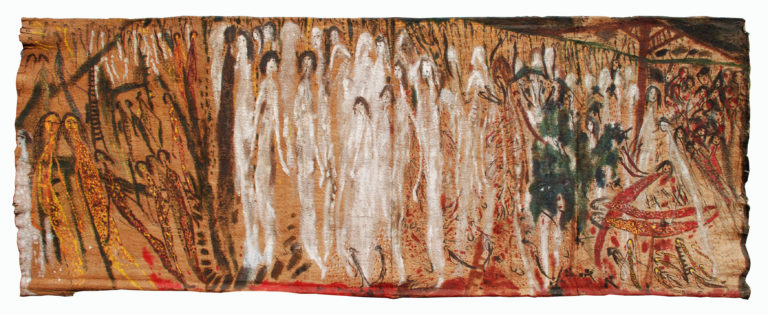

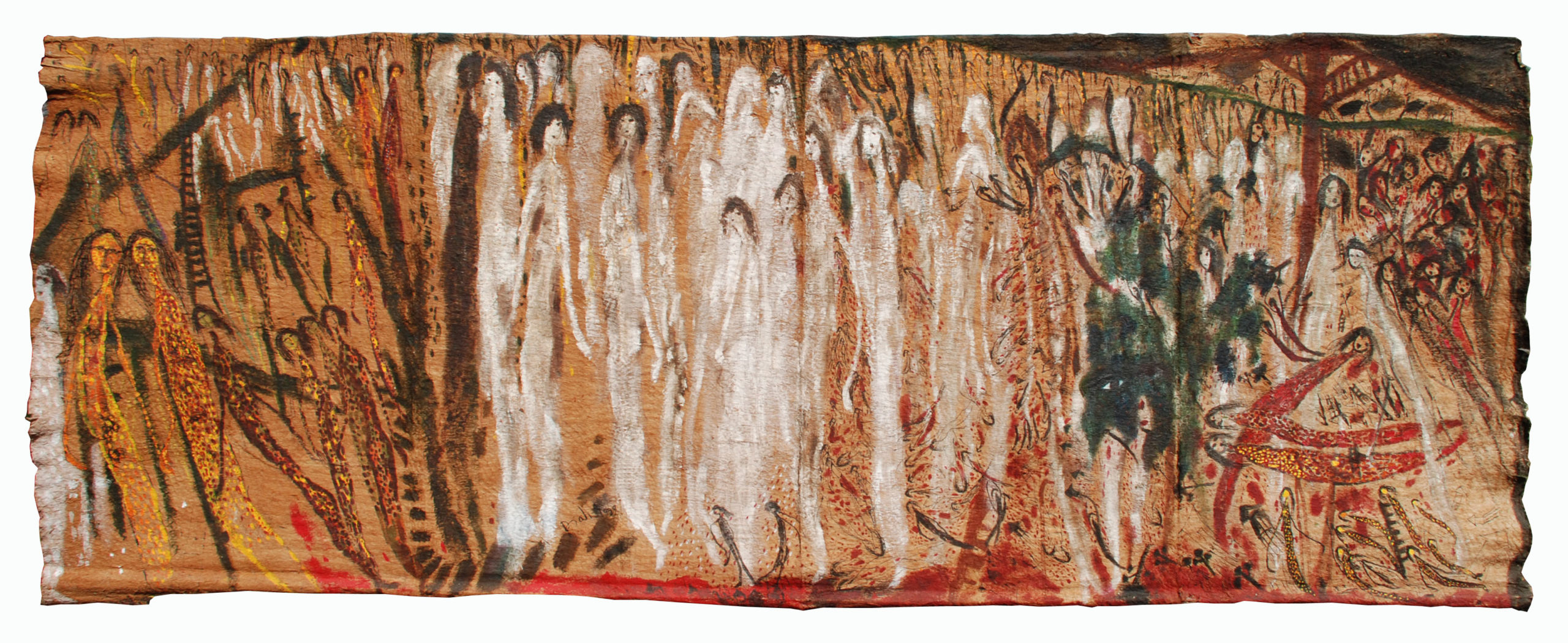

In this section, I discuss an autobiography penned in Indonesia in 1950, a year after the country’s formal independence from the Netherlands. Indonesia is an especially interesting case for considering nationhood because it is host to one of the largest Muslim populations in the world. Moreover, it encompasses vast linguistic and ethnic diversity, a territory spread over more than seventeen thousand islands, and a history that includes a mixture of British, Dutch, and Japanese colonial regimes during the period 1800–1949. Muhamad Radjab (1913–1970), the author, wrote as an adult while recalling his life from birth to teenage years in West Sumatra as a part of the Minangkabau peoples. The work ends as he leaves the village to become a part of the emerging Indonesian nation.

Radjab’s passage from a Minangkabau boy to Indonesian adult shadows the evolution of populations identified by their ethnonyms becoming citizens of a modern nation-state. The work’s narrative is focused on the homosocial village sphere consisting of boys and men, which is especially interesting because the Minangkabau are a matrilineal society in which lineage and property passes between generations via links between women rather than men. In part due to the matrilineal social structure, the Minangkabau are especially known for producing male Islamic scholars in Southeast Asia.

In Radjab’s self-description, he was expected to take up the role of an Islamic scholar in the community. His disinclination toward this occupation fed into his view of Islam as an imprisoning condition, which he eventually overcame by leaving Sumatra. His later profession as a journalist, who wrote in Indonesian, the national language, was in many ways the radical opposite of being a Muslim ritual expert like his father. It made him a mouthpiece in the language that unified the nation looking to the future.