Biographies of Sufis—of which there are an immense number, spread throughout the world and over more than a thousand years—defy some expectations we may have of the notion of famous people. Consider, for example, the following description of a person proclaimed as someone worthy to be commemorated:

He had asked God to remove his good repute from the hearts of the world. When he was absent he wasn’t missed and when he was present no-one sought his advice, when he arrived in a place he was accorded no welcome and in conversation he was passed over and ignored…He suffered from a tied tongue and spoke only with great difficulty, but when he recited the Quran his delivery was excellent. His spiritual work was great and he earned his living as a henna siever (Ibn ‘Arabi, Sufis of Andalusia, 115).

While not all Sufis may have desired the degree of anonymity sought by this person, the general idea that a life pursuing closeness to God required limiting material desires and social relations has had wide currency among Sufis. And yet it is also the case that most forms of Sufi thought require that practitioners have guides who provide training through embodied performance. The double imperative—that great Sufi masters withdraw from the world while also acting in it as teachers and exemplars—gives Sufi recounting of the past a distinctive cast.

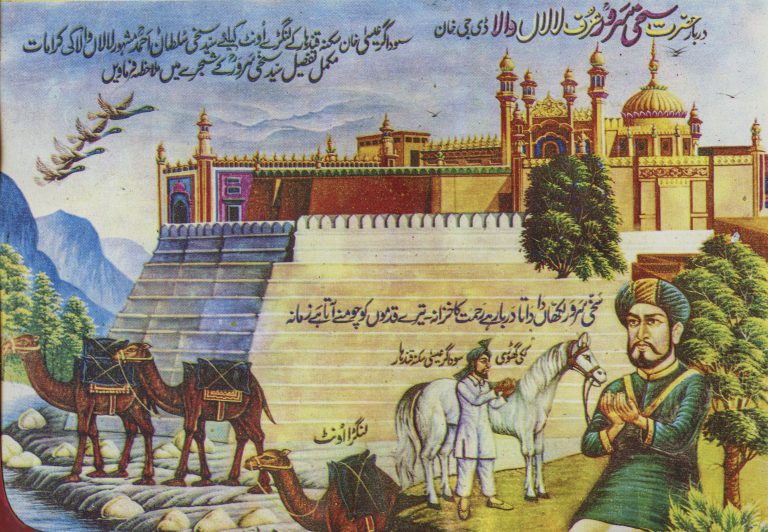

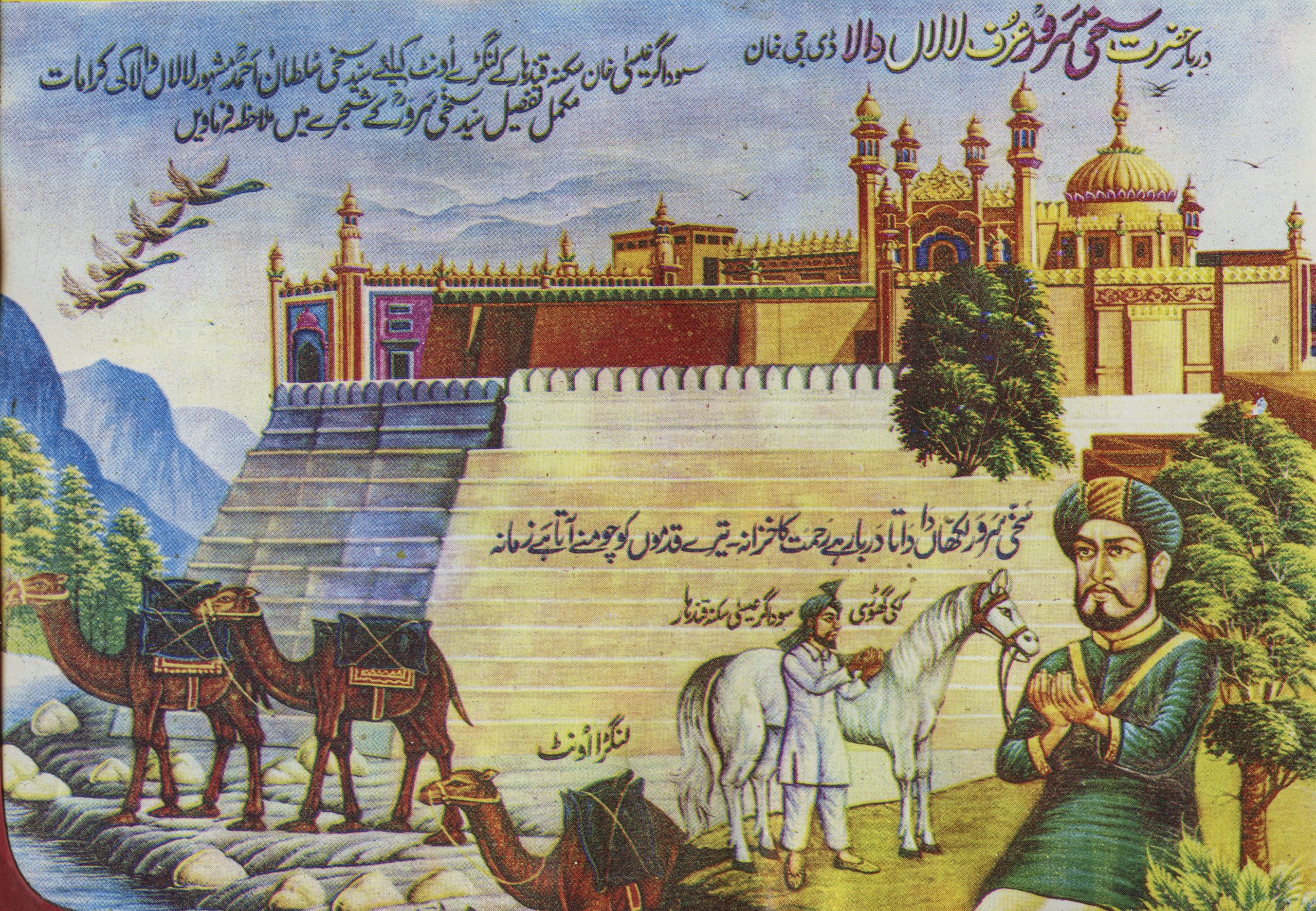

To get the measure of Sufi hagiography (saintly biography), it is necessary to attend to both the genre’s social underpinnings and the specificity of its representations. For the social side, hagiographies are created by disciples seeking to bolster the saintly credentials of people whom they regard as legitimizing their own practice. This means that these works are constitutionally partisan. When hagiographers know the persons being described, they ensure to bring themselves into the story as observers of special circumstances and receivers of blessings. When subjects are in a distant past, lessons from lives lived long ago are interpolated into the situation of authors’ present. Hagiographies are therefore always a mixture of biography and autobiography due to narrators’ deep religious investment in what is being described.

Hagiographical stories describing great Sufis follow patterns within and across narratives. They revolve around a fund of familiar tropes that create contrasts between apparent circumstances anyone can see and hidden truths available to the cognoscenti. For example, the outwardly unassuming, tongue-tied person described in the report I quoted above is meant to be understood as a man of great religious accomplishment. The hagiographer’s claim is that this person’s outward appearance belied his knowledge and, moreover, the hagiographer himself possesses the special knowledge to discern such people from the crowd.

In most cases, hagiographical descriptions point to Sufis’ shunning the world as a sign of their religious greatness. But the process can occur in reverse as well, when those who are successful in the world are shown to shun material trappings in their interiority. The key issue in hagiography, therefore, is special knowledge that characterizes the saintly figures being described and enables hagiographers to correlate between appearances and their hidden meanings.

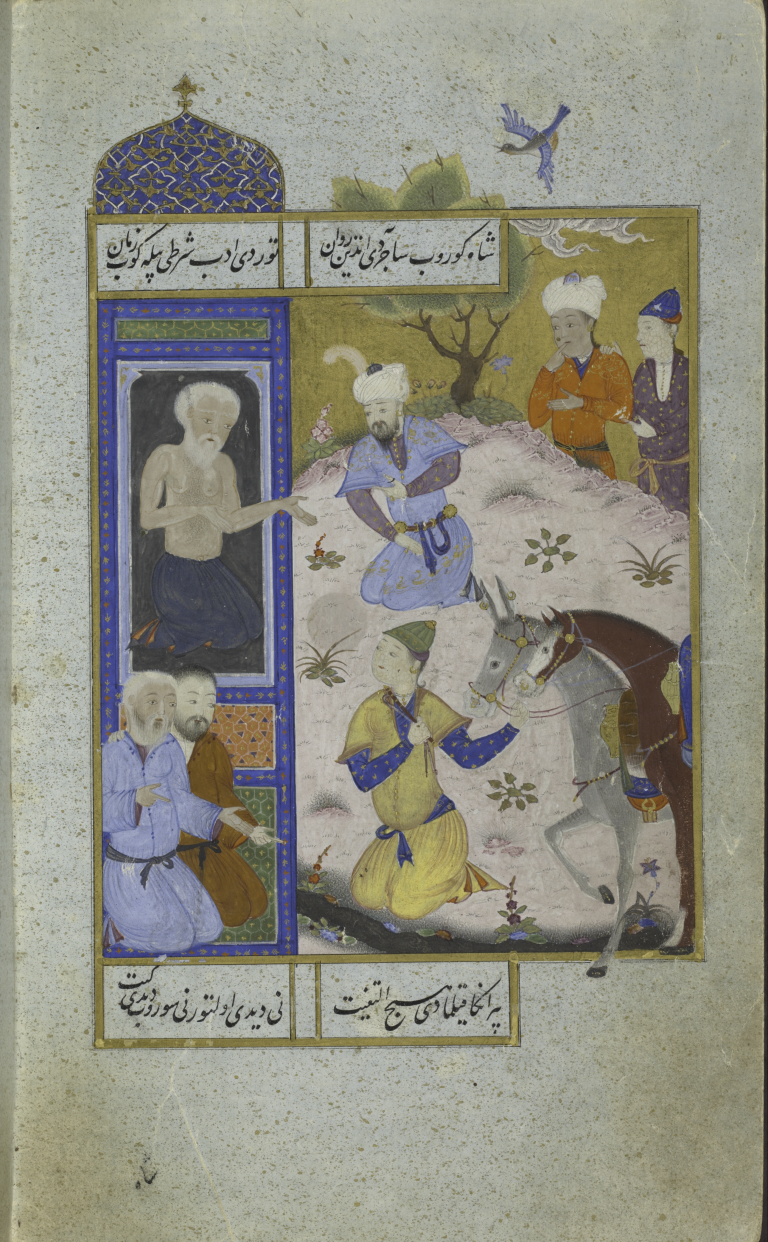

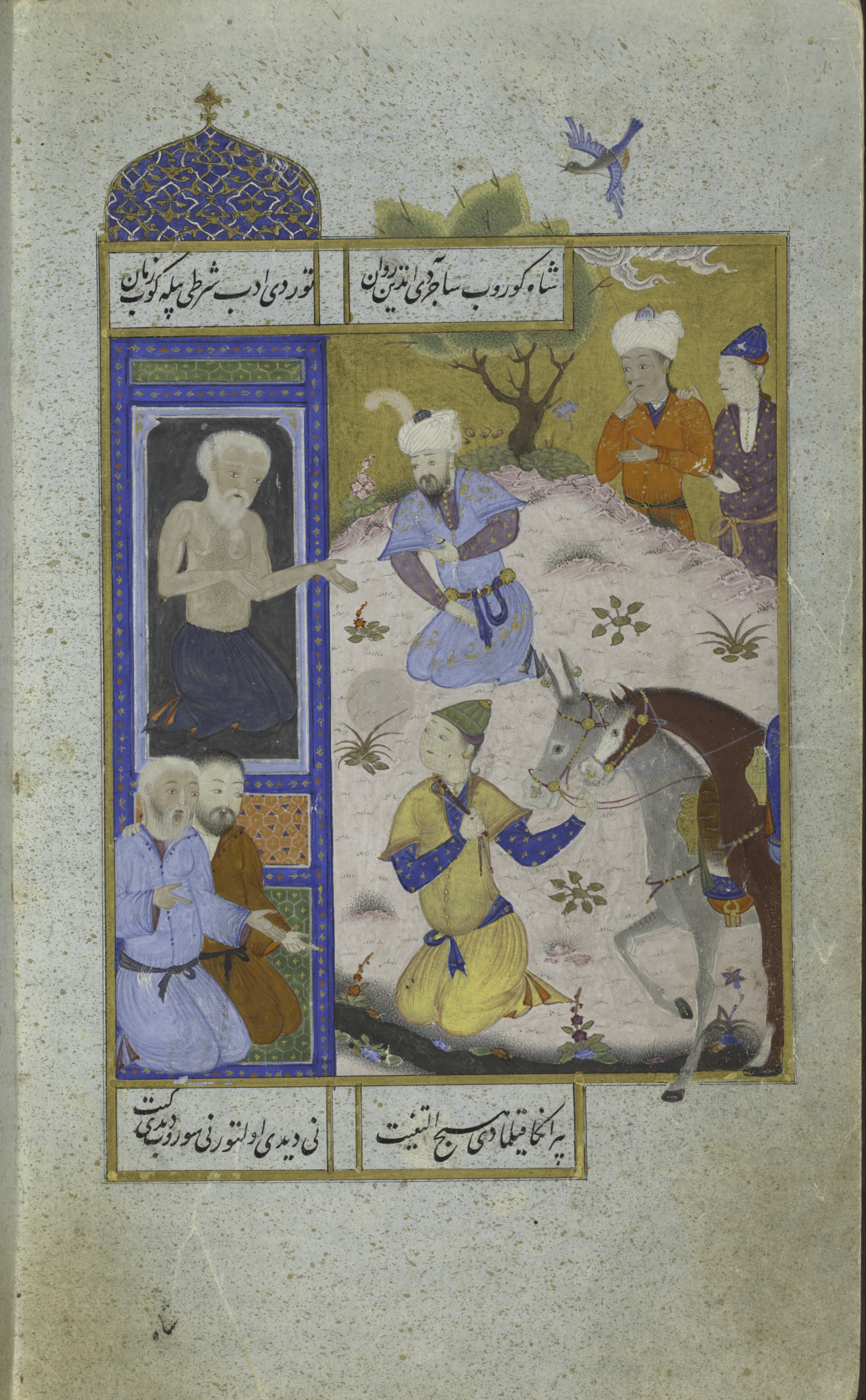

To illustrate aspects of Sufi hagiography as a genre, in this section I describe a thirteenth-century work on southern Spain and North Africa, from which comes the description I have cited above. Entitled Ruh al-quds fi munasahat an-nafs (The Holy Spirit for Advising the Self), this is a work by Ibn ‘Arabi (d. 1240), a towering figure of Islamic intellectual history. Ibn ‘Arabi is known for his voluminous mystical writings, whose significance grew exponentially in the centuries after his death. He spent the first thirty years of his life in his native Spain, later traveling through North Africa, the Arabian peninsula, the Levant, and Anatolia. He died in Damascus, from where his disciples carried his works, full of literary and theoretical virtuosity, to many corners of the world. During the period 1300–1800, many aspects of Islamic intellectual life throughout Africa and Eurasia were conditioned by responses to Ibn ‘Arabi’s ideas. His imprint on intellectual cultures can be found in fields ranging between personal piety, cosmology, literature, art and architecture, and political theory espoused by empires.