The word tabaqa, Arabic in origin but used in many languages, has a range of meanings pertaining to classification. It can suggest layer, sedimentation, and social class or a floor in a building. As a measure of time pertaining to Islam, it was used extensively as the designation for biographies of people in generations as these were measured with respect to proximity to the Prophet Muhammad. The fist tabaqa in this sense consisted of the Companions (sahaba) who had direct contact with Muhammad. After that came the Followers, then the Followers of Followers, and so forth such that “the layers” (tabaqat) became the name for narrating the past as arranged in a sedimentation of successive generations. Over the centuries, the chronographic principle involved in such an arrangement became more generalized, now being used for all categories of people. We have, then, tabaqat works for not just Muhammad’s followers but also for genealogies of scholars in various traditions, initiatic lineages, courtly secretaries, doctors, poets, noteworthy women, and so on.

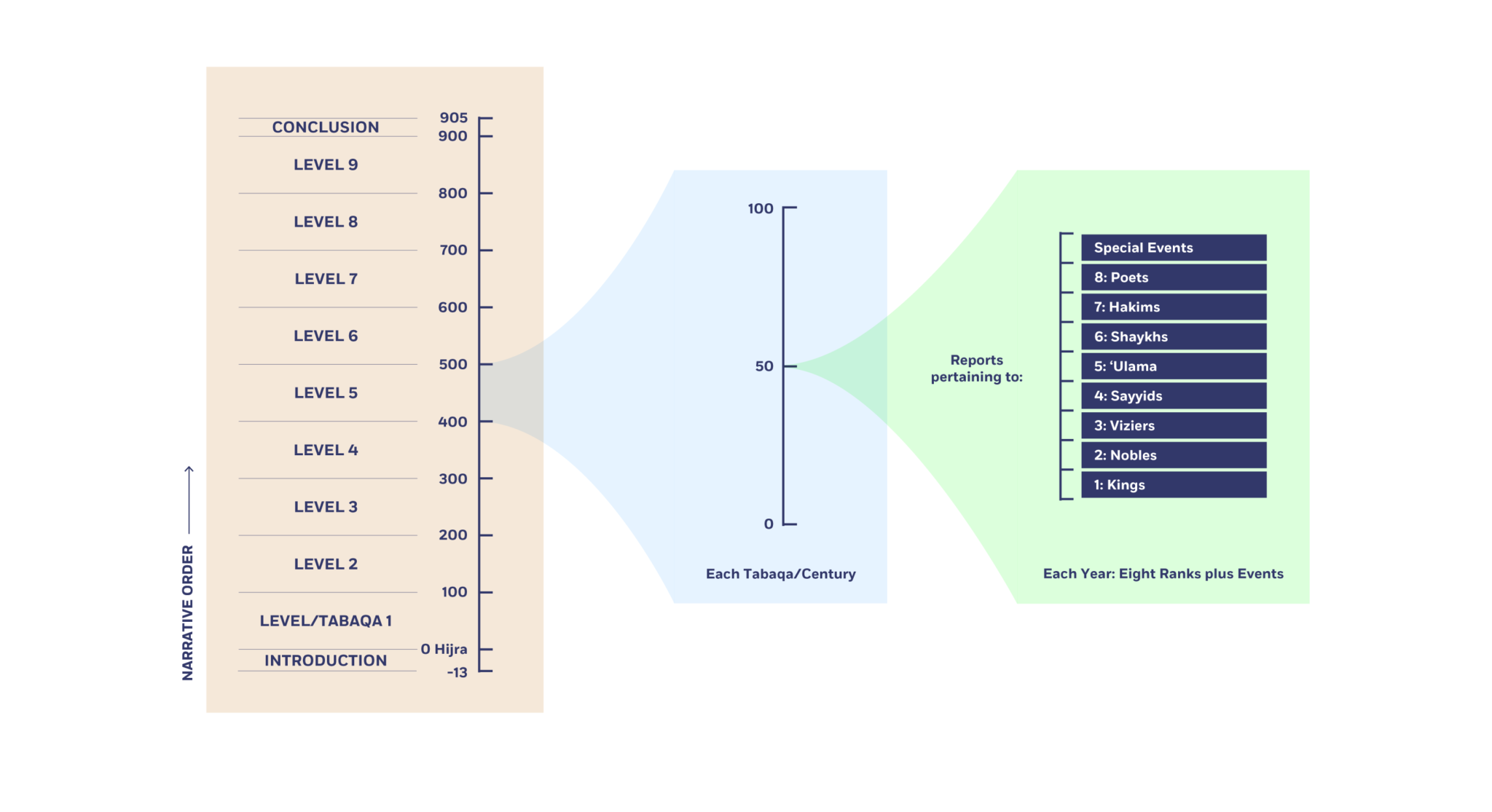

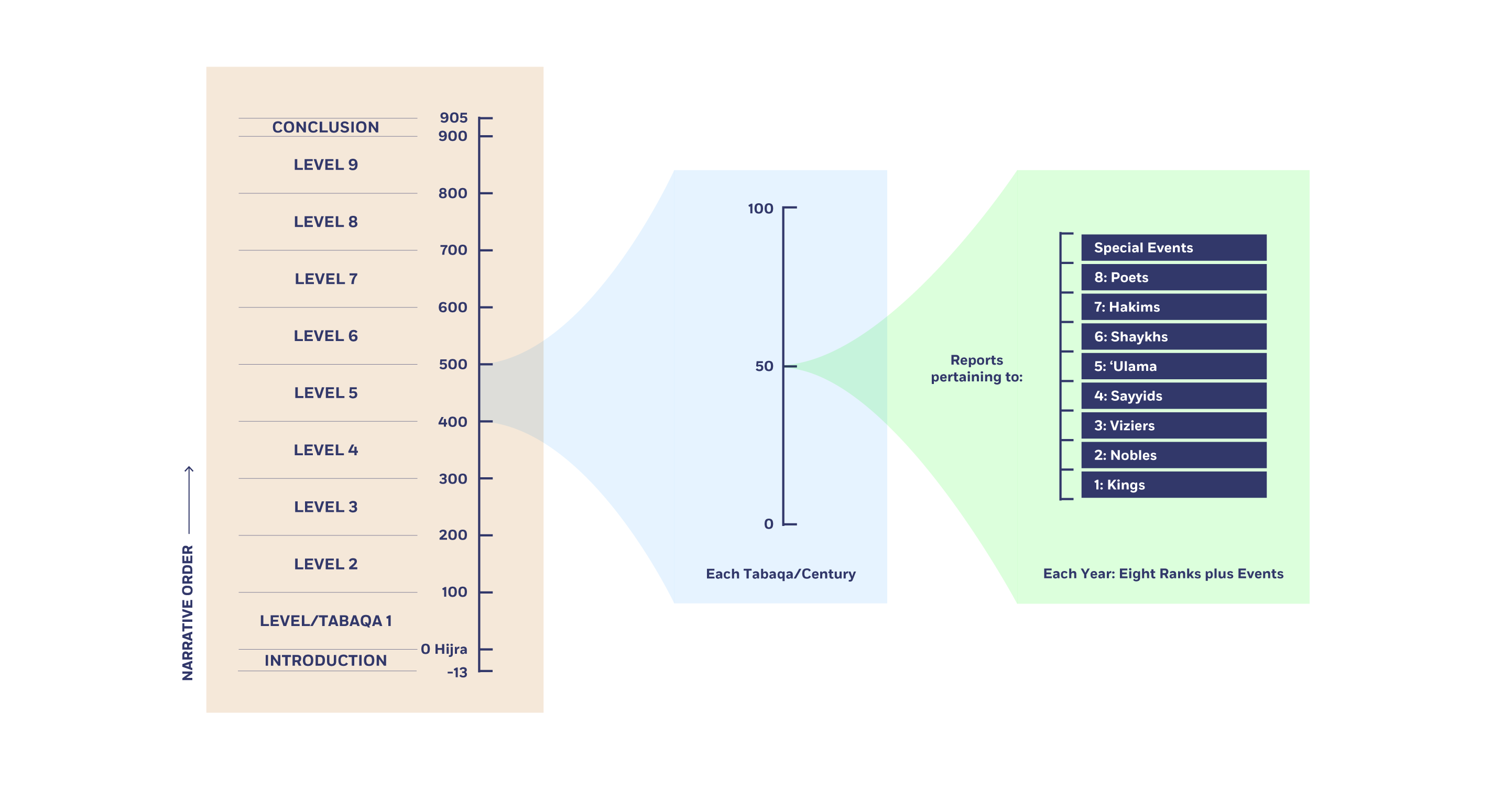

As presentations of the past, literary works in the tabaqat genre focus on individual biographies as elements that accumulate as time elapses. Their detailed contents are almost always a braiding of two temporal orders: one, the “type and generation” principle that puts individuals into a narrative sequence, and two, calendar-time measured from a point of orientation, such as Muhammad’s migration that began the Hijri era, that must be cited to peg lives to a universal scale.

Since people put into a single generation can live and die at different times relative to each other, the calendar is necessary as a secondary principle that provides an unmarked temporal understructure. When one reads these works, they understand people put in the same tabaqa are roughly coeval to each other but are differentiated within and across tabaqas based on varying temporal extensions that mark their lifetimes between birth and death.

The tabaqat genre is a highly inflected form of chronography. When life stories are sequenced based on a typological principle (companions of Muhammad, poets, women, etc.), the resulting “history” slices peoples’ lives out of their surrounding spatiotemporal contexts and makes them seem related to each other across generations. People belonging to a category put into a diachronic sequence project the sense of a “community” consisting of individuals who had no possibility of interacting with each other.

For example, a tabaqat work on female scholars spanning many generations might include one person from the ninth century and another from the thirteenth. When encountered textually, through the choice made by an author, we are asked to see the two women as being part of the same community. But such an impression is a literary sleight of hand made possible by the reification of the classificatory principle. This effect makes tabaqat works literary guarantors of traditions that claim to represent authoritative communities accumulating over time from an originator to later proponents.

The prominence of tabaqat in Muslim literary cultures has significant ideational and sociopolitical consequences. The genre makes Islam, or subsidiary sociointellectual formations, appear self-evidently “real” in historical terms. To show how this occurs, I will describe a work entitled Tabaqat-i Mahmud Shahi (The Tabaqat of Mahmud Shah) that was completed in Gujarat, India, circa 1500 CE. Composed by a learned bureaucrat and chronicler named ‘Abd al-Karim Nimdihi, this is a highly political work undertaken under the sponsorship of an ambitious ruler, Mahmud I “Begada” (r. 1459–1511).

The work puts the tabaqat principle into operation in a complex and unusual way, allowing us an especially instructive view into the genre’s effects. Mahmud Begada’s investment in historical representations leading up to his own career as the apogee extended beyond Nimdihi’s work. It included a large-scale capital city at Champaner and a Sanskrit work entitled Rajavinod Mahakavyam composed by a poet named Udayaraja. A discussion of the Sanskrit work after I describe Nimdihi’s Tabaqat will further help us to see how variation between biographical genres leads to radically different temporalities pertaining to a single sociopolitical context.