A Fictional Autobiography

Mernissi spent her early life in Fez as part of an elite Muslim family invested in the city’s reputation as Morocco’s religious center. In 1994, she published a book in English entitled Dreams of Trespass: Tales of a Harem Girlhood that was marketed as an autobiography, told from her viewpoint as a child while growing up in a multigenerational household. Absent in the English version but indicated in a footnote in the French translation is the acknowledgment that the book was actually fiction of a certain type:

If I had tried to tell you my childhood, you wouldn’t have finished the first two paragraphs, because my childhood was dull and prodigiously boring. As this book is not an autobiography, but a fiction that presents itself as tales told by a seven-year-old child, the version of the facts about January 1944 told here is the one that was in my memories. Memories of what illiterate women told each other in the courtyard and on the terraces (translated in Bourget, “Complicity with Orientalism,” 33).

The discrepancy between the two versions of Dreams of Trespass gives insight on Mernissi’s attitude to the past. Presuming that the difference has to do with her goals for writing—and not a desire to deceive or cash in on celebrity status— paying attention to the publication venue and her statements regarding the fictional content in her work is especially productive.

The fact that Dreams of Trespass was first published in English tells us that in writing it, Mernissi had a global audience in mind, with an emphasis on North America and Western Europe. The word harem in the subtitle of this book (as well is in the titles of many of her other books) is a further clue. As a scholar has pointed out, Mernissi’s books were published at a time when harem was a word “unfamiliar in current Moroccan usage. If the space the word ‘harem’ designates existed historically, it has disappeared from Moroccan reality today” (Rhouni, Secular and Islamic Feminist Critiques, 132).

This means that when Moroccans, or other Arabs and Muslims, encounter the word in Mernissi’s works, they see a past purportedly of their own societies but refracted through the Western gaze. This is not to say that the seclusion of women denoted by the harem is unknown to them. Rather, naming such seclusion as harem is a function of using English or French (rather than Arabic) and comes encumbered with the orientalist imagination that has made the term familiar to Western audiences.

Mernissi’s work is heavily invested in trying to dispel incorrect understandings of Muslim women she felt were common in the West. Does this mean that her use of the term harem was a cynical ploy to sell more books? It seems to me that the situation is more complex and has to do with the way colonial and orientalist projections regarding the Islamic past play a determining role in modern Muslims’ self-understandings. Mernissi’s ultimate purpose was to effect change in societal attitudes as well as legal regimes as they pertained to women. Such change is largely a prerogative of national governments and international discourses such as that of universal human rights. Intervening in these domains requires writing in European languages in which harem is a native term and is the most efficient way to name the problem. Counterfactually, if Mernissi’s concern were solely to affect the discourse among Arabic speakers, the harem would have been irrelevant and she would have had to use different terms.

Mernissi’s prominent deployment of the word harem was a kind of bait-and-switch tactic. It drew readers to her books, whether titillated by the vast Western reservoir of sexual fantasy or seeking to liberate oppressed Muslim women from presumed servitude. What they found in her descriptions (including in the pseudo-autobiographical Dreams of Trespass) was a complex reality in which seclusion was presented as a situation of disempowerment but not of desubjectivization or dehumanization. The women she described resisted impositions and had lives that were joyful as well as difficult. The lesson in her works was directed toward people in the West and elites within places such as Morocco. The harem for these audiences was, in her view, a basic fact of the Islamic past whose tentacles reached into the present. By first enticing and then adding complexity, Mernissi’s work was a discursive interruption into this fabric of thought.

If we grant sincerity of purpose to Mernissi, her presentation of a fictional narrative as autobiography makes sense because of the subject position she understood herself to occupy. To put it simply, she was a Muslim woman writing to cause change in her own society via addressing herself to people who presumed her to have been formed by a historical imperative structured along the lines of a harem. To say that the harem was an irrelevant word and the social situation of her concern was more complex would not garner the audience’s interest. Conversely, enticing by citing the harem and then providing an eminently readable account, put in the mouth of a child presumed incapable of guile, was a highly effective strategy. Through this, she adopted the name the presumed audience undertook to represent reality and attempted to imbue it with nuanced content.

Dreams of Trespass is a highly artful text. Reading without knowing that it is fictional is likely to seduce many readers into thinking it represents events, especially if one is inclined to think sympathetically about Muslim women. This accounts for the book’s extensive adoption in universities in Europe and North America as a text representing Muslim women’s lives in the early twentieth century. Should we think of this situation as Mernissi having duped readers by a fake? Her own response to this issue was oblique: she suggested she was narrating a truth conveyable only through invention.

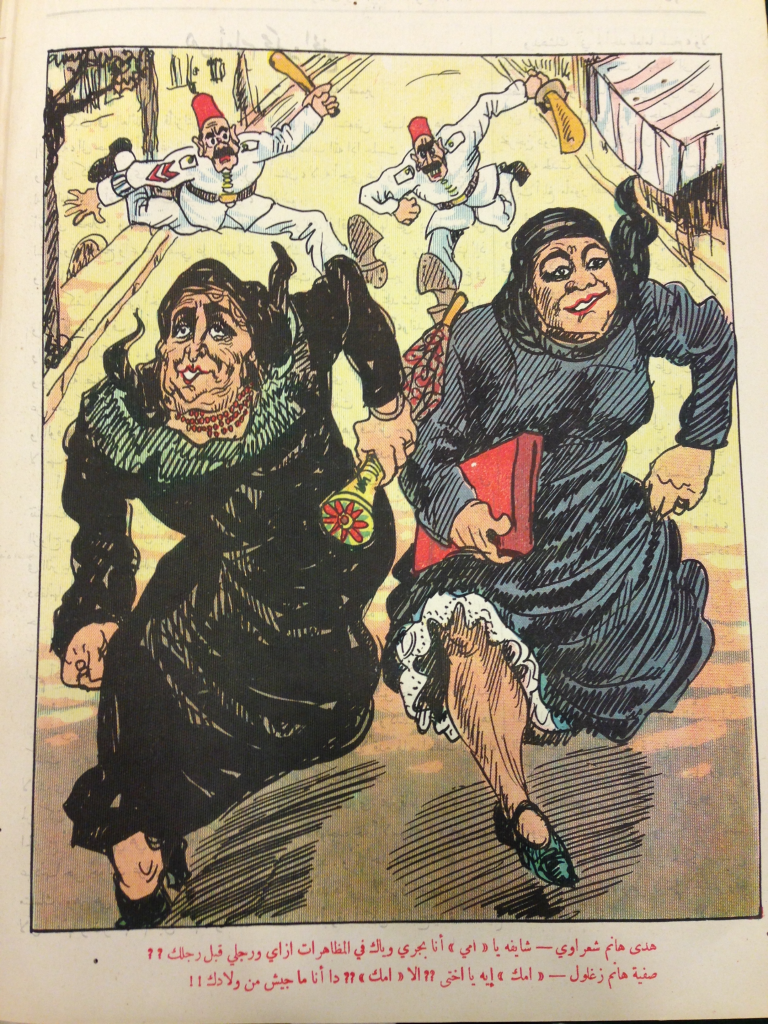

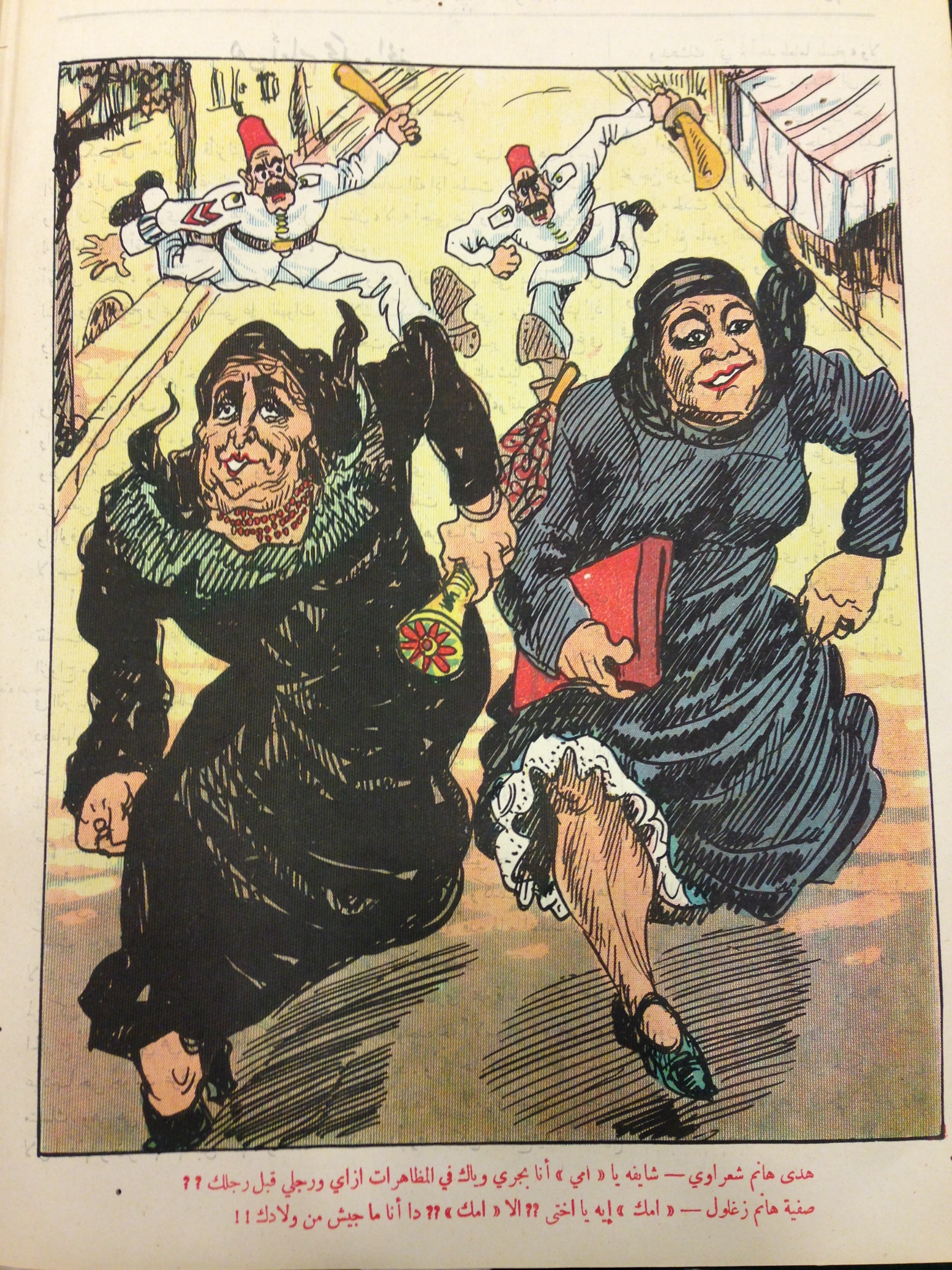

A satirical magazine’s portrayal of the feminist activist Huda Hanım Sha’rawi and Safiyya Hanım Zaghlul pursued by Egyptian policemen (1931).

Source

A satirical magazine’s portrayal of the feminist activist Huda Hanım Sha’rawi and Safiyya Hanım Zaghlul pursued by Egyptian policemen (1931).

SOURCE

al-Kashkul, 22 May, 1931, Rare Books Library and Archives, American University in Cairo, Photo Gülşah Torunoğlu

The first-person voice she had manufactured for the work was a reliable narrator, an adult who had a lifetime of experience as a woman in Morocco and articulated it through the constructed voice of a precocious child looking to the future. The book consisted of anecdotes she had heard, and taken to be true, rather than experienced. Additionally, the manufactured autobiographical voice allowed experiences coming from multiple sources to congeal into the narrative of an individual.

Mernissi’s conceit was that her awareness of women’s lives in Morocco was such that an invention she posited as her own consciousness as a child was an appropriate vessel to narrate the collective recent past. The autobiographical ruse was akin to how a historian may narrate the salient characteristics of an age through the biography of a paradigmatic person. In such a work, the life of the protagonist acts like an artificial center that allows arranging others around them to create a picture of the surrounding world. The key for Mernissi was the need to create a personable story that would ring true as the description of a time anterior to the late twentieth century when her book was published. And this story’s ultimate purpose was to generate sympathy and better understanding in the target audience, based primarily in Western countries.