This book’s discussions signify time via three terms: past, future, and horizon. The intuitively obvious “past” and “future” refer to human creative effort. They consist of imagination regarding what happened before our experience and what might happen after our current situation. Using the word imagination here emphasizes that pasts and futures result from acts of the mind. They come about through factors such as our desire to understand matters beyond what is available immediately via the senses, presumptions about the way the world works, what others have conveyed to us in words, deductions we make from observing materials under varying frameworks of comprehension, and projections about what is yet to happen.

Additionally, the future objectifies our anticipations. It derives heavily from what we take to be the past while also shaping aspects of the past that are found meaningful in a given context. The way we imagine the past, and what we decide to see in it as significant, depends on the state of our apprehensions. The interdependence between the past and the future funnels through the location from where the two are imagined.

In my perspective, the here and now—the “present”—equates to “horizon” and is categorically different from the past and the future. When I describe my present situation, the resulting narrative object will be the past the moment my fingers hit the keys on the keyboard. The present is therefore not an aspect of imagination but a positionality that can only be inferred indirectly. It is the location from which an observer, a thinking and articulating being, imagines pasts and futures.

Our understandings of pasts and futures are predicated on our positionalities. We can also imagine other positionalities that are not the past or the future for us but which we can posit as the positions that led to the generation of evidence available to us. We can appreciate pasts and futures other than the ones intuitive for us. Pasts and futures—and the positions of which they are, or were, a part—can be transformed into each other, all performing varying functions for human agents.

The horizon is an efficient visual metaphor to convey that, in considering time, to move the observer is to cause a change in the world under observation in a particular way. As I see out while standing in an elevated place, the horizon is a line that bifurcates my view. It generates senses of closeness or distance. When I move in any direction, the line moves with me, simultaneously changing the positions of all the other objects within my vision. Moving forward or backward brings previously invisible elements into my vision. The horizon’s stillness or dynamism depends on change caused by the one observing it.

The visualized horizon provides an intuitive pathway to understand time as a constant whose particulars are perpetually changing. Our understanding of time issues from a position toward a horizon that has the past and future as objects. The position and the horizon change in tandem as the observer moves, shifts viewpoint, chooses to direct sight to one place or another, and considers relationships between what is being observed.

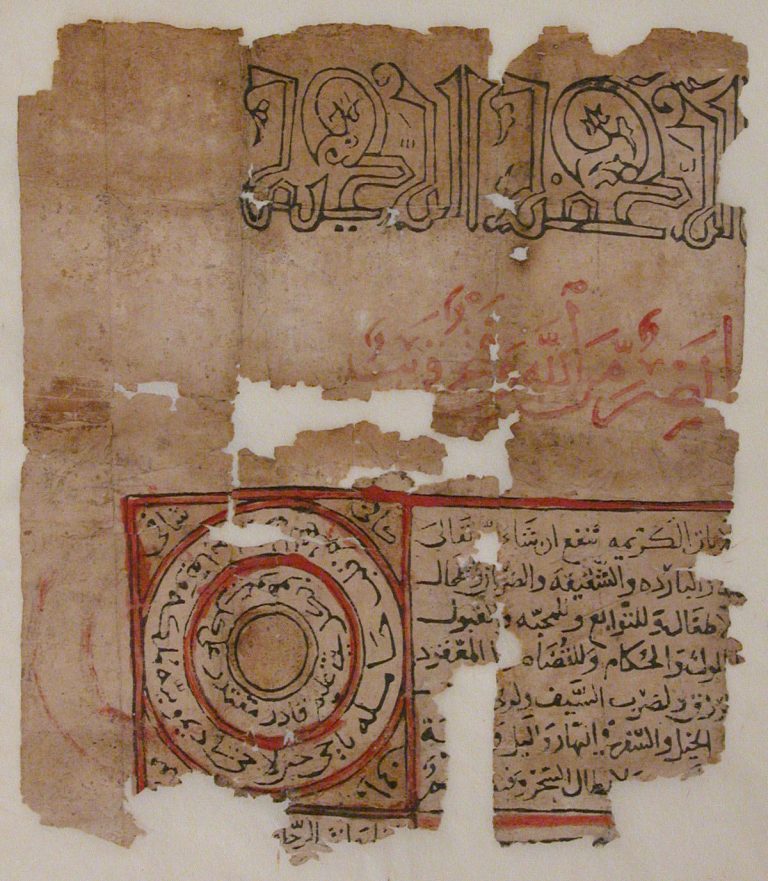

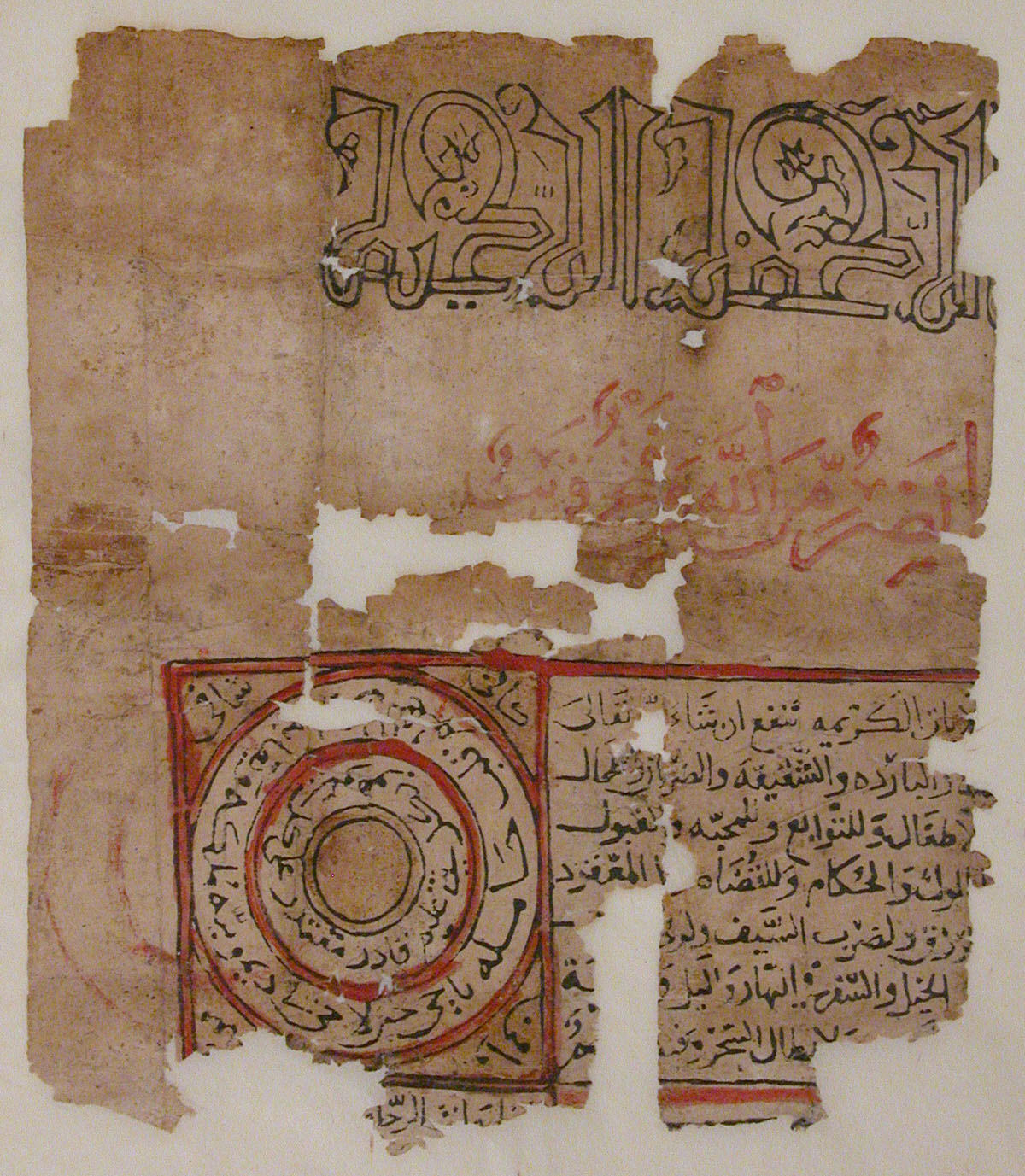

Time may be understood objectively (a measurement that indexes the flow of life) or subjectively (the experience of being present momentarily at a given place). It can signify both the history of a community covering centuries and an instance in which one person experiences something. Both modalities are found inscribed in artifacts of human endeavor, such as speech, texts, paintings, and buildings. My way of thinking about these artifacts consists of my horizon, which is laden with particular ways of knowing and understanding. The Islamic pasts and futures I can see are composites that take shape, and transform, as I examine artifacts as repositories of time.

It is crucial that I make a distinction between my horizon and those of others who would not share my positionality. When interpreting objects produced in the past, I must acknowledge that what I see in them is not always what would be visible or valuable to others, including to those who produced the artifacts. Making note of the difference allows me to concentrate on clues within the artifacts and, based on the observations, to imagine horizons other than my own. The changeability of perspective allows me to treat the evidence as a Pandora’s box that opens when addressed using the view of time I have adopted for this book.

This approach squarely acknowledges that horizons, and their respective pasts and futures, cannot be described or reconstituted exhaustively. Knowledge of pasts and futures is always partial. For us, those who lived in the past had pasts and futures that are perennially translucent. But our very failure to recover horizons in full is the engine that drives our investment in them. While our horizons are not the same as of those who were positioned differently, the multitude of horizons bear intimate connections.

The desire, indeed need, to know the past and the future is a crucial component of all selves facing horizons. Pasts, futures, and horizons—all of them subject to endless variation—affect each other as they transform continually. Understanding time in this way allows us exceptionally rich views into the dynamics of the human condition.