Journey to Karbala

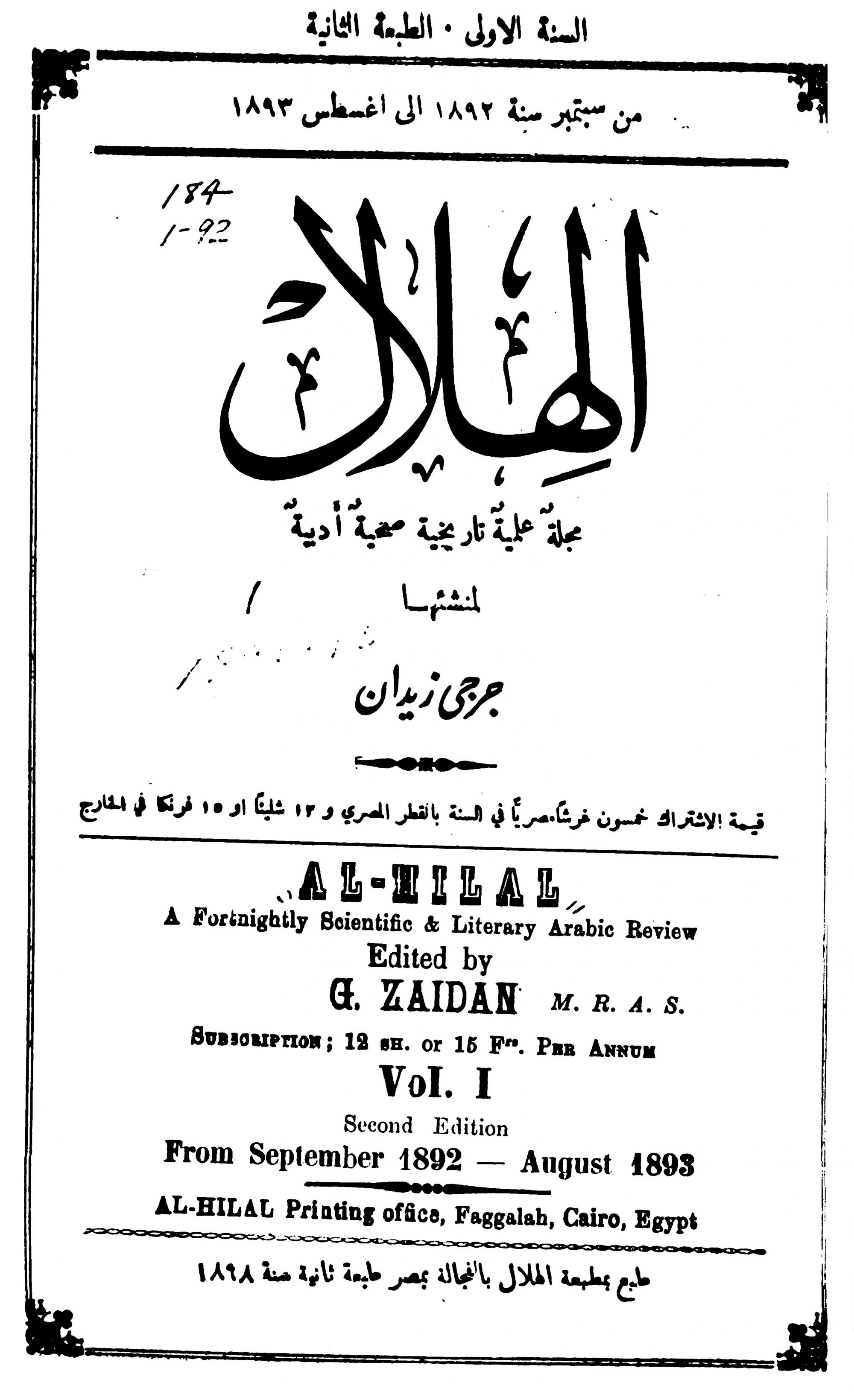

The first chapter of Ghadat Karbala is not fictional at all (1–2). It is a short summary describing the Quraysh tribe in which Muhammad was born, the political and military success of his immediate followers and their internal disputes, and the establishment of the Umayyad dynasty with its capital in Damascus. The second chapter (2–4) describes the fertile region called Ghuta (often Ghouta in modern spelling) that surrounds the city of Damascus. These summaries of time and space are given in an impersonal, encyclopedic voice, informing the reader about the real past within which the fictional story will be set. While fiction takes over from the third chapter, the voice marking real history reappears numerous times, reminding the reader of the past’s facticity.

Zaidan’s presentation of summary historical information is a quick refresher meant for a reader who knows the overall story already. This expectation is expressed directly in chapter 9, entitled “The Fact of the Matter,” which is placed after the main characters of the fictional story have been introduced. It begins with the following:

The reader must have understood from the foregoing that Salma [the “young lady”] was the daughter of Hujr b. ‘Adi, killed at the meadow of ‘Adhra’, and that ‘Abd ar-Rahman was her cousin, and the two were engaged, and that ‘Amir was their guardian. The details of this are that Salma was born in Kufa eight years before her father’s killing and had been entrusted to ‘Amir’s wife for breastfeeding and that she had been with her in the desert. This was a practice common among Arabs. … ‘Amir had been a frequent visitor to the Levant for trade, especially with the Sabaeans and the Banu Kinda, who remained Christian. When he came to Damascus, he would stay and frequent monasteries and churches. He would sit with knowledgeable people, who would relate aspects of Greek history and its relationship to the history of the Levant and other places. He remembered all this, understood it, and became counted among the most knowledgeable people, with the widest information about history. In Salma, ‘Amir intuited intelligence and the inclination to explore stories of origins. To her, he would relate reports he had acquired about the Persians and the Byzantines, and their interrelationship (15–16).

The character ‘Amir described here is an alter ego for Zaidan himself. Like him, Zaidan had acquired knowledge of the past from many troughs. His (and Zaidan’s) custodianship of Salma involves both the duty of protection and making her a repository of historical knowledge. Also important is that ‘Amir and Salma are early Muslims who learn from Christians. Zaidan’s own position with respect to religion worked in reverse. Of Christian origin, he had learned about the Islamic past to the degree of becoming its authoritative mouthpiece.

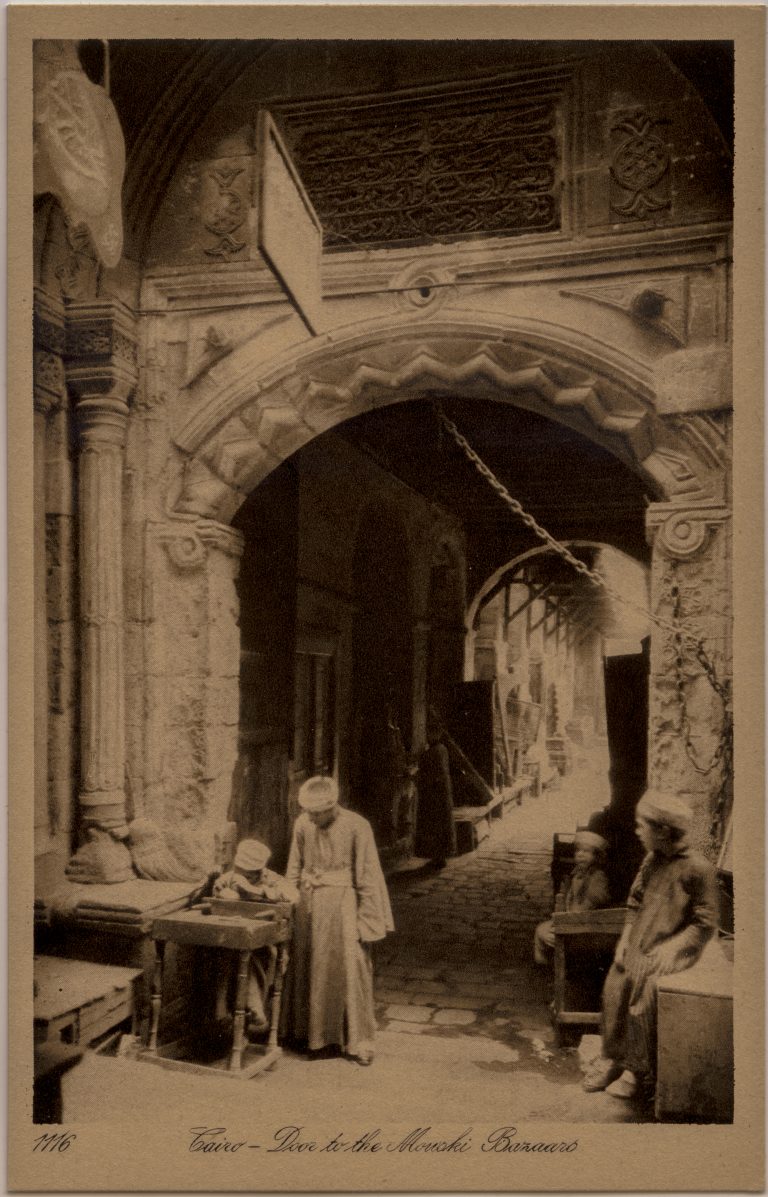

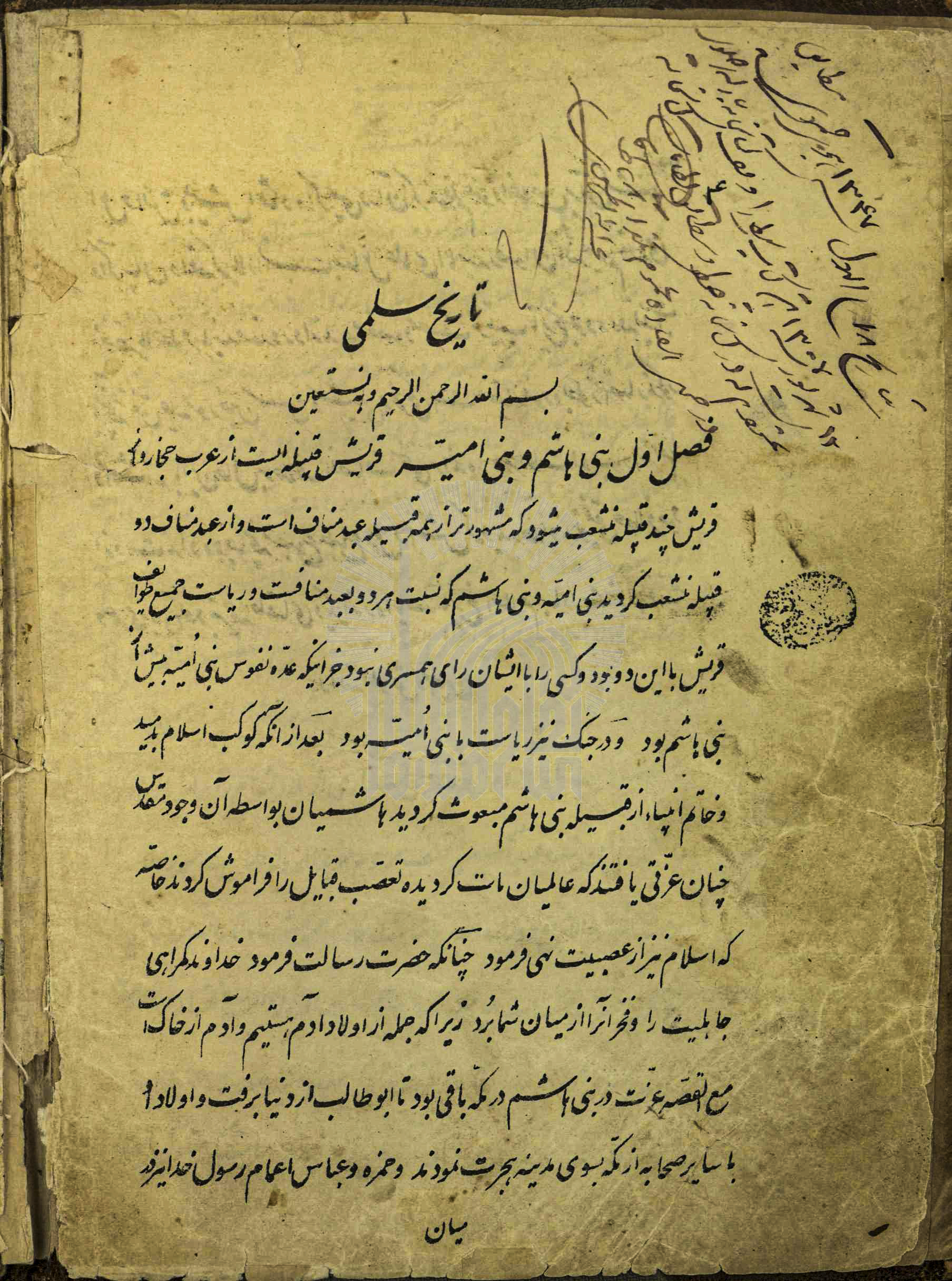

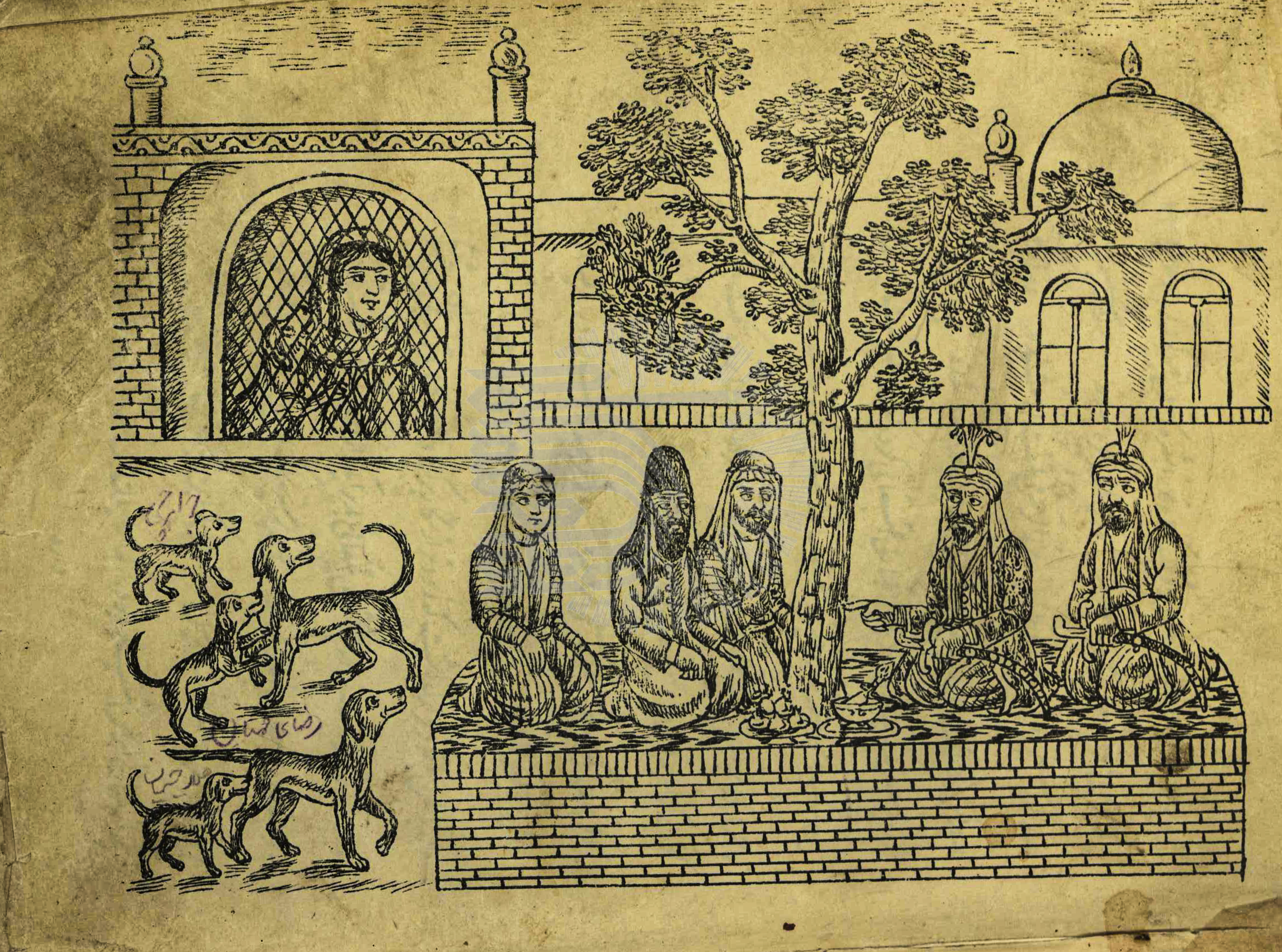

TarikhSalma2

Print showing Salma observing a gathering in which Yazid is accompanied by his dogs (p. 73).

SOURCE

Jurji Zaidan, Tarikh-i Salma, tr. ‘Abd al-Husayn b. Mu'ayyad ad-Dawla Tahmasp Mirza (Tehran: Shirakat-i Matbu‘at-i Dar al-Khilafa, 1903), p. 73

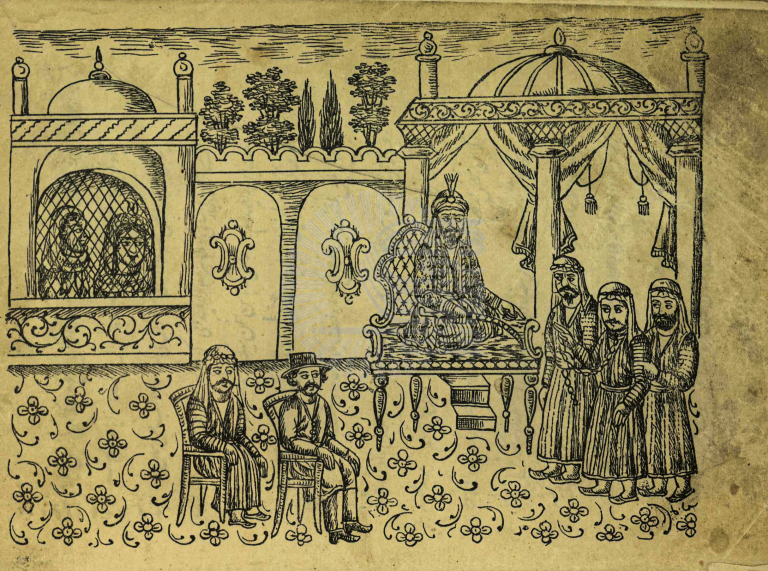

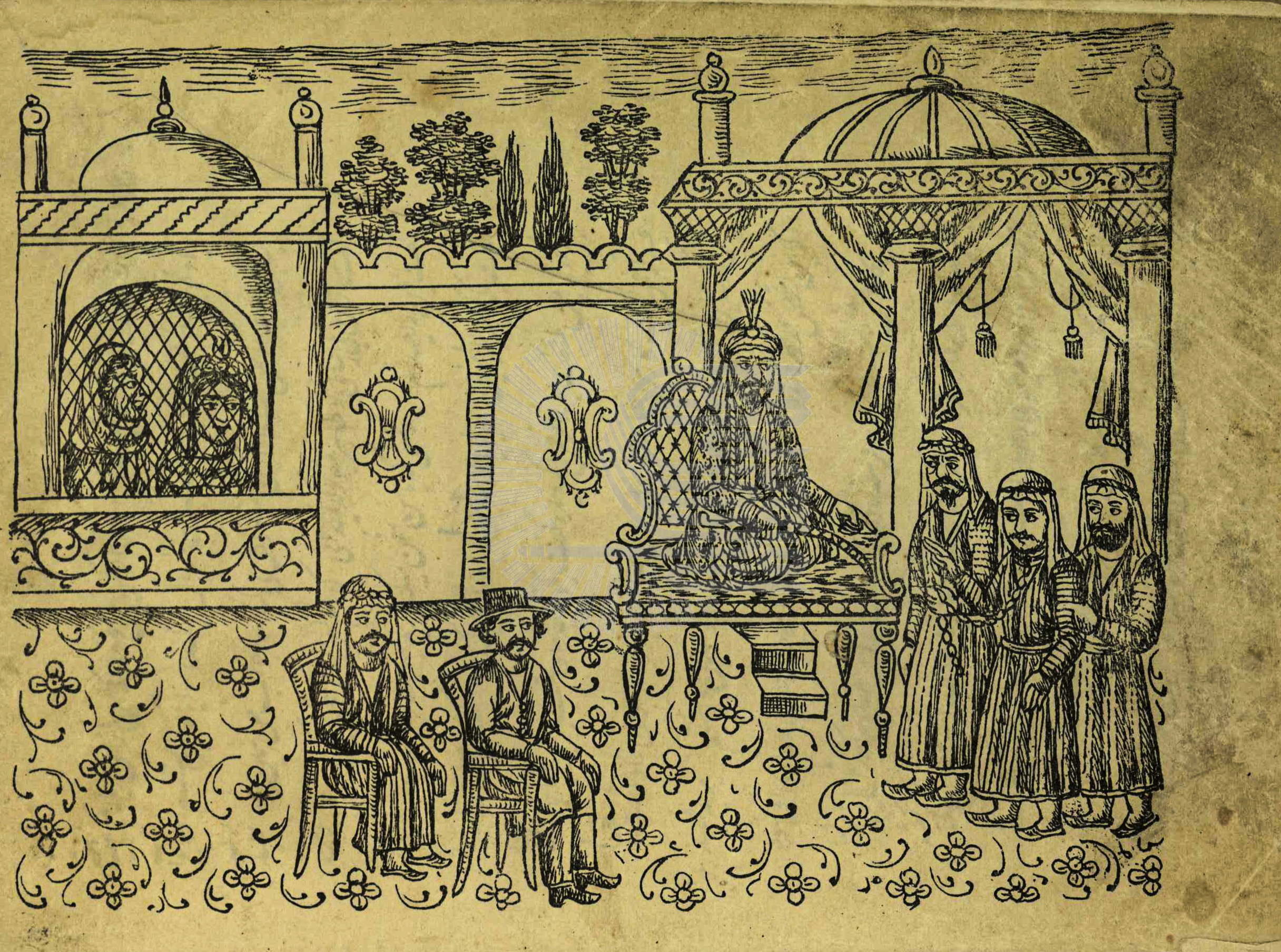

Salma’s cousin and future husband ‘Abd ar-Rahman interrogated by Yazid. She observes the encounter from a hidden position.

SOURCE

Jurji Zaidan, Tarikh-i Salma, tr. ‘Abd al-Husayn b. Mu'ayyad ad-Dawla Tahmasp Mirza (Tehran: Shirakat-i Matbu‘at-i Dar al-Khilafa, 1903), p. 174

Go to next slide

Go to next slide

Zaidan’s historical framing derives from accounts he had absorbed from the work of European orientalists. While he had clearly read many Arabic sources that discuss this history, his mode of presentation mimics modern academic writing rather than attempting to inhabit voices found in premodern sources. The most noteworthy issue here is how his attempt at objectivity contrasts with what premodern authors might do. For the latter, neutrality meant providing as many conflicting accounts as possible to prove the disputed nature of past occurrences. In contrast, partisan premodern authors narrate the past as a matter of ultimate moral truth. Zaidan’s method is different: he conveys a processed neutrality, the past as a set of facts established through deduction that are also not being used for religious or other ideological arguments.

While Zaidan replicates the orientalist posture with respect to knowledge of the past, there is one crucial difference: for him, this is not the history of “others” who live far away in the Orient. Instead, the Islamic past is a crucial component in the history of all Arabic speakers, like the author himself. Through this displacement, Zaidan leverages an orientalist epistemology for a local identity. The transformation he and other proponents of the Nahda accomplished would eventually lead to the rise of a multireligious Arab nationalism, and his novels were crucial predecessors for Arab nationalist movements. They incorporated Islam and Muslims into nationalist ideologies but without making religion the primary basis for collective identity.

Seven of Zaidan’s twenty-one historical novels have women as the titular protagonists. His choice on this score was partly clearly due to his interest in highlighting and promoting women’s wider participation in political life. This was a prominent topic in materials from all over the world in which he was immersed as a maker of public opinion. Zaidan’s female leads are beautiful, brave, and noble, embodying the best ideals of the worlds in which they are placed. They become the period’s raconteurs while also embodying a moral conscience that runs contrary to corrupt and disgraceful behavior.

The first description of Salma, the young lady of Ghadat Karbala, presents her to the reader as seen from the eyes of a Christian abbot who welcomes a traveling party to the monastery (at the end of the novel, the abbot turns out to be Salma’s paternal grandfather):

The third [person in the party] was a girl, whom the leader examined intently on account of her extraordinary beauty. The like of her he had not encountered in his long residence in Damascus and its surroundings, among the abundance of girls from the Byzantines, the Arabs, the Nabataeans, the Assyrians, and the Jews. Before this moment, his eyes had never rested on a girl whose face had such beauty and dignity. The beauty of her eyes stood out, which although they were not as big as that of her young male companion, were sharp and full of light. … He said to himself, even if poor in possessions, this girl’s father is rich because of her (8).

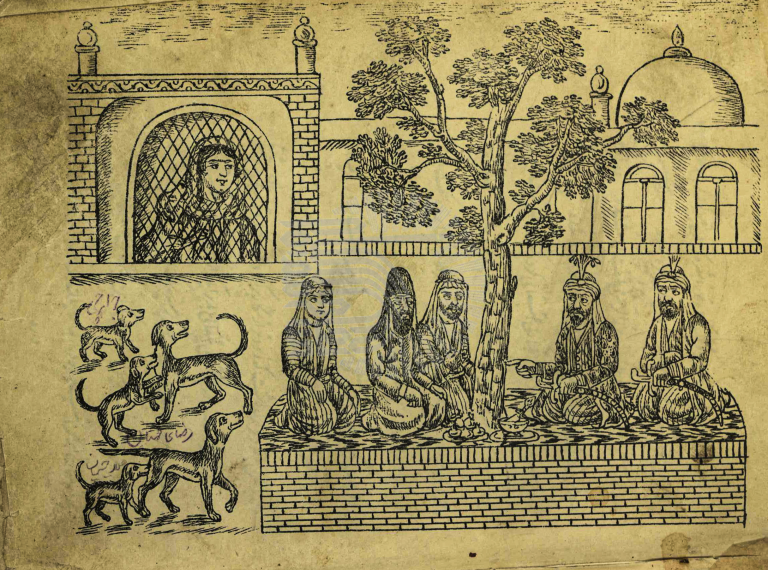

Salma’s outer beauty is a counterpart to her inner fortitude, which includes her interest in knowledge about the past. As an observer of her surroundings, Salma offers the further benefit that her eyes can see more than what is available to her male counterparts. She has unrestricted access to households’ inner spheres, including that of female figures who feature in history. Moreover, when the female character observes the public world dominated by men, she often does so from behind a screen or curtain. She observes without herself being observed, a position also often occupied by the narrator of historical fiction.

While Salma is fictional, her putative father, Hujr b. ‘Adi (d. 660), is a well-known historical figure renowned as a member of the party of ‘Ali (Shi’at ‘Ali) active in early disputes among Muslims. Her father’s violent death at the hands of proponents of Mu’awiya (‘Ali’s chief rival and the father of Yazid, who would eventually order the killing of Husayn) is disclosed to Salma within the novel’s narrative at a scene next to his grave (21–24). This is presented in the voice of her custodian ‘Amir, an eyewitness, with footnotes to Ibn al-Athir (d. 1160), a celebrated chronicler.

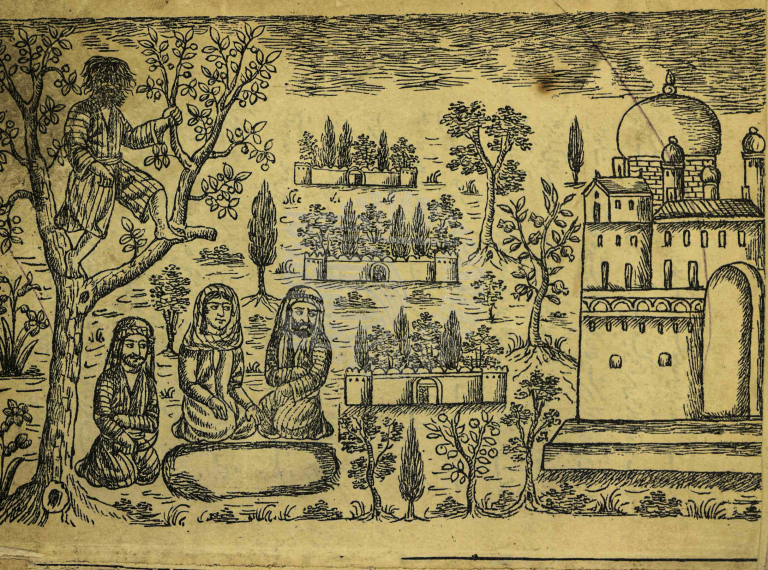

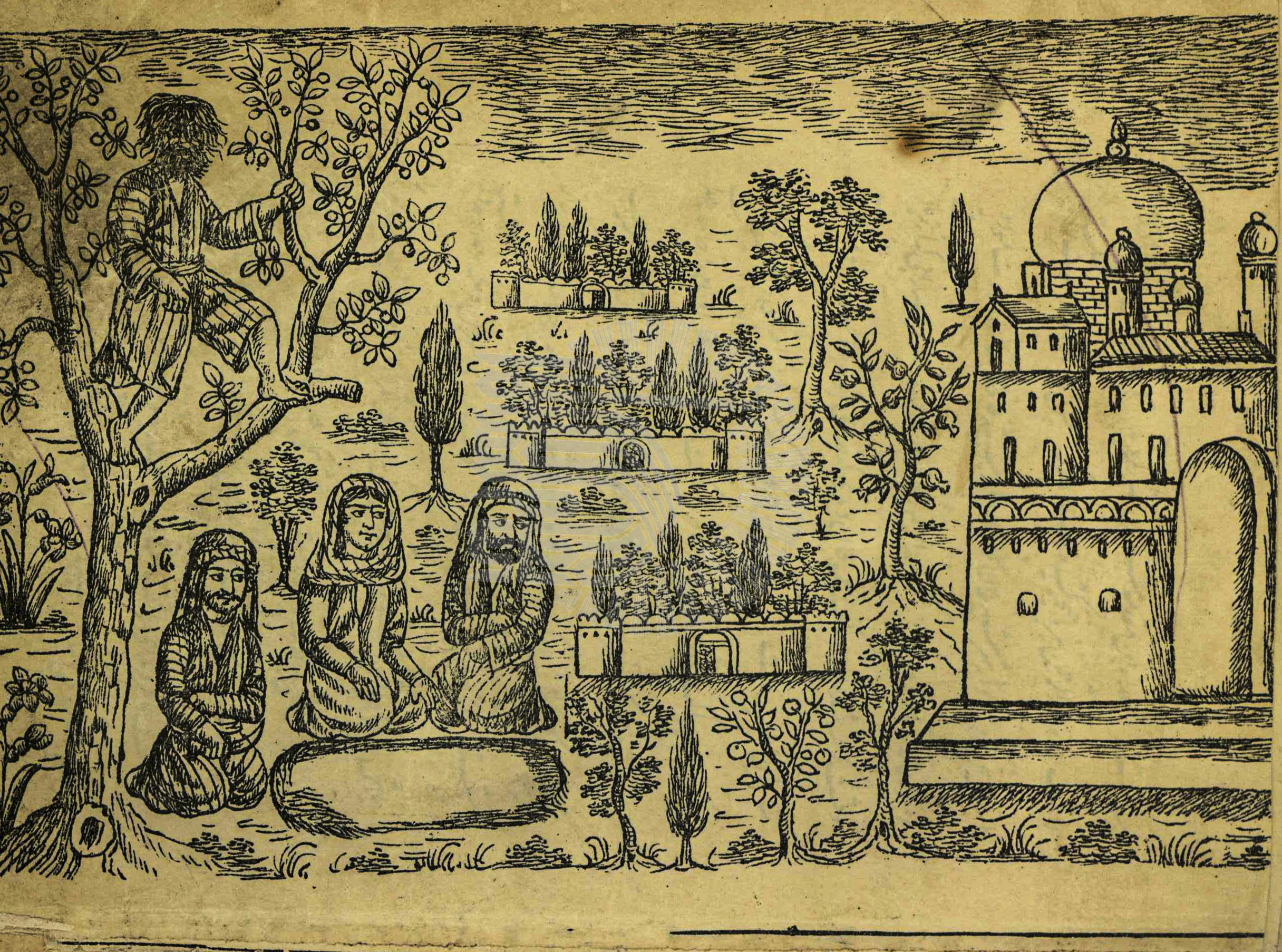

Salma and ‘Abd ar-Rahman are overcome with anger and grief when the story finishes. While the man vows to avenge his uncle, Salma holds a fistful of the grave’s dirt and looks to the sky while beseeching God for justice. Then a disembodied voice speaks out from the grave enunciating the quasi-Quranic statement “To those who tyrannize, give the good news of a painful punishment” (the Quranic verse [9:3] says “those who disbelieve” instead) (25).

Salma and others at the tomb of her father Hujr b. ‘Adi. He speaks to her as a disembodied voice from the grave, pictured in the tree.

Source

Salma and others at the tomb of her father Hujr b. ‘Adi. He speaks to her as a disembodied voice from the grave, pictured in the tree.

SOURCE

Jurji Zaidan, Tarikh-i Salma, tr. ‘Abd al-Husayn b. Mu'ayyad ad-Dawla Tahmasp Mirza (Tehran: Shirakat-i Matbu‘at-i Dar al-Khilafa, 1903), p. 53

This scene sets the novel’s narrative fully into motion, leading Salma and ‘Abd ar-Rahman to the court of Yazid in Damascus and various other locations in Syria and Iraq. Numerous historical and fictional characters enter and exit the story as we hear of the main characters’ actions and emotions. Salma eventually arrives in Kufa and the nearby Karbala. Here she becomes witness to various episodes pertaining to Husayn and his companions that figure prominently in later accounts and are commemorated every year across the world.

Zaidan’s account of events connected to Husayn includes aside comparisons with much later times, such as that of the Abbasid caliphs, the Ottoman Sultan Selim (d. 1520), the Ottoman governor of Egypt Muhammad ‘Ali (d. 1848), and Napoleon Bonaparte (d. 1821) (151–152). It is as if he cannot let go of his position as a modern historian even when the fictional frame requires avoiding such anachronisms.

In the part of the narrative that deals with Husayn’s last days, Salma becomes a companion to his sister Zaynab b. ‘Ali (d. 682), who survived the bloodshed at Karbala (161–163). Salma is also depicted as a direct witness to Husayn’s brutal death:

She saw the group of men attack him, one hitting him on the left shoulder, cutting it, and another on the other shoulder. Husayn fell to earth, face forward. Salma shouted, unaware of what she was saying, “Woe to you, you have killed Husayn … your faith is dead.” The shaykh recognized her and grabbed the tail of her garment, even as she was oblivious to him, her eyes on Husayn as he lay next to the corpses of his children and brothers, his blood mixing with theirs, although he was not dead. She saw Shimr jump on him, his hand on his sword. He struck his neck with the sword, cutting until he was decapitated. After a moment, Salma heard a snort. Then she saw Shimr raise the head in his hand, its covering having fallen away, hair exposed and smeared with blood, eyes closed. He gave it to a man with him, telling him: “Take it to Amir ‘Umar b. Sa’d” (184).

Iranian feature film on Hujr b. ‘Adi (2003). His death via arrow is depicted at the very end (1:40:00).

The story continues for a time after the description of this pivotal event. We are told of Husayn’s companions who survive, and Salma and ‘Abd ar-Rahman are reunited after having been separated and not knowing each other’s fate. There are other revelations regarding relationships between characters. At the end, the two cousins go to Mecca, get married, and spend the rest of their lives in loving company in territory that is not controlled by those who had killed Husayn (i.e., the Umayyads) (224).