Gardens of Time

Completed in 1667–1678 in Isfahan, Muhammad Yusuf Valah-Isfahani’s Khuld-i barin (The Highest Paradise) is a massive universal history that purports to tell the story of the material world from its birth to the author’s own day. Its contents follow patterns found in a long list of earlier works, selected and inflected according to the author’s own preferences and the requirements of his situation as a client to the Safavid dynasty that ruled Iran between 1501 and 1722 CE.

The longest, seemingly nearly complete, surviving copy of Khuld-i barin runs to more than 1,800 manuscript folios (3,600 pages), its sheer volume making it a grand repository of information received from earlier literary sources (Nicholson, Descriptive Catalogue, 96–100). The work’s most extensive coverage is reserved for the period close to the author’s own lifetime, defined by rulers of the dynasty he served. For events that fall nearest to him, the author’s reports cited from earlier sources are augmented by eyewitness accounts. The work typifies politically sponsored Islamic chronicles before the nineteenth century, conceived in the grandest terms. Its framing and contents reflect the intimate connection between narration of the past and political legitimacy in Islamic contexts.

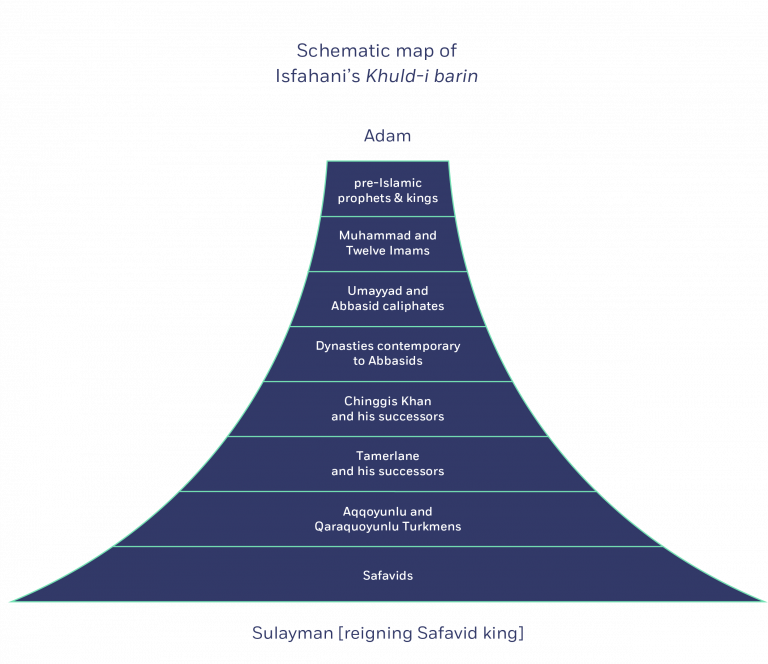

Flow of time in Isfahani’s Khuld-i barin.

Source

Flow of time in Isfahani’s Khuld-i barin.

Valah-Isfahani’s use of the word paradise as the name of his chronicle is an instance of describing time through spatialization. He invites the reader to see the past as a series of gardens, which themselves consist of a succession of meaningful events. The “gardens of time” proceed in order from the distant past to the present, increasing in volume. Each of them is divided further into smaller enclosures, allowing the author to apportion matters into subordinate categories. Time as event and time as narrative are operational simultaneously in this situation.

At the base level, time consists of the events that form the narratives of the lives of the main characters who define the ages in which they lived. The sequence of things that happened to Muhammad from birth to death, for instance, describes the prophetic age that initiated Islam. These events are then put into an overarching series, forming the author’s metanarrative that takes the reader from creation to the seventeenth century CE.

The flow of time one encounters on the surface of the narrative begins at the year zero of human existence and proceeds to the present time of writing. However, attending to what is included and excluded from the narrative, we can be sure that political and social imperatives of the author’s own context drove his choices. This purportedly universal picture of humanity is actually limited in frame to those human figures of the past whose authority fed into the political legitimacy of those in power in the author’s present.

The world we see in this work is restricted to figures defined as prophets in Islam and only those royal lineages that had ruled over the region that had eventually become Safavid territory. Its massiveness notwithstanding, the Khuld-i barin is an account of the past that mattered to Safavid elites alone and would have appeared truncated and inadequate even to Valah-Isfahani’s contemporaries residing outside Safavid territory. However, this observation is hardly an indictment. Far from being an exception, this work’s parochial and self-interested nature is a quality common to all narratives of the past.

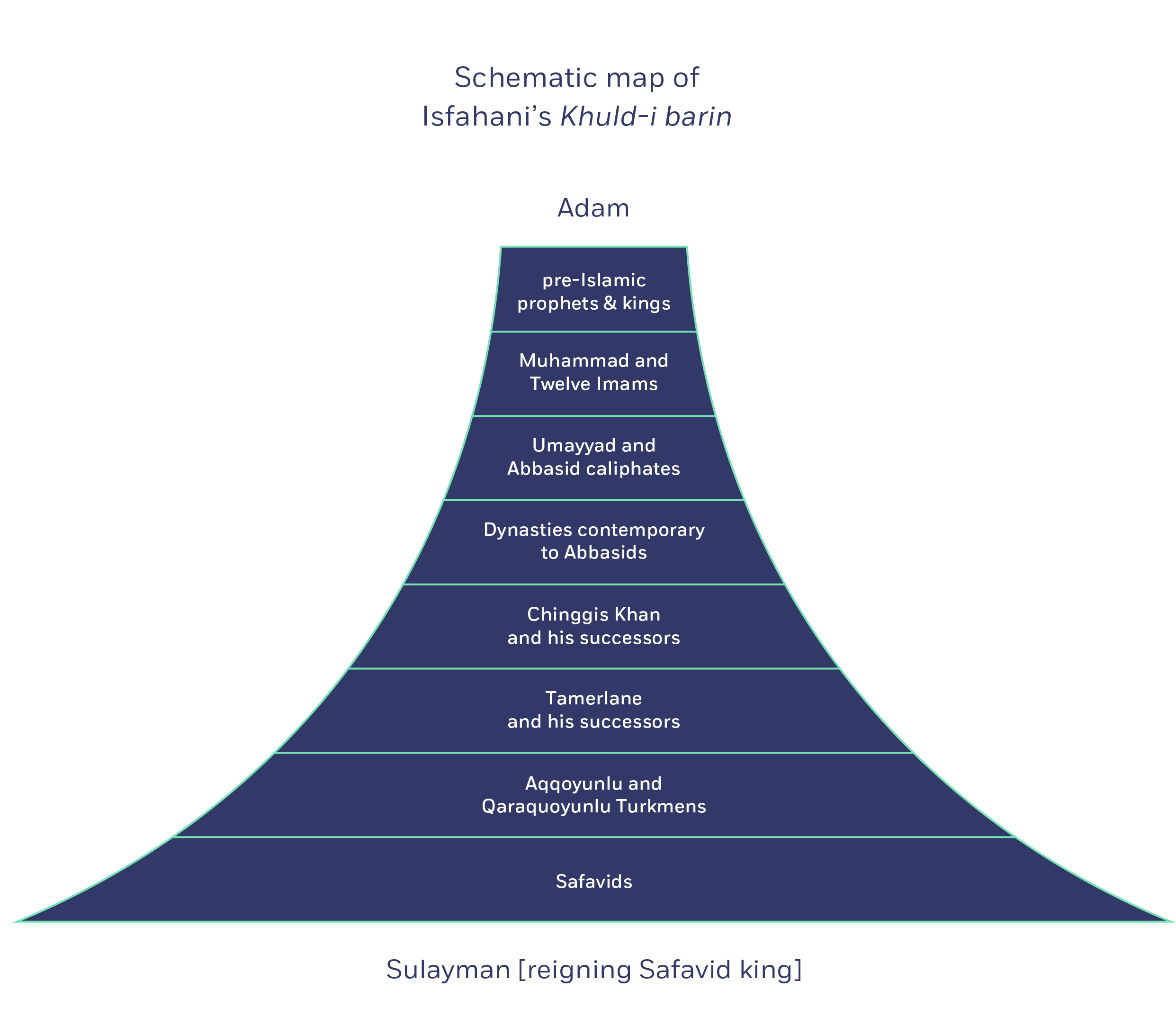

The Prince’s Garden in Mahan, Iran (ca. 1850) follows the classic Persian pattern in which a water stream from the mountains is directed through a terraced enclosure. Valah Isfahani’s Khuld-i barin is a textual implementation of this form of a garden.

Source

The Prince’s Garden in Mahan, Iran (ca. 1850) follows the classic Persian pattern in which a water stream from the mountains is directed through a terraced enclosure. Valah Isfahani’s Khuld-i barin is a textual implementation of this form of a garden.

SOURCE

Photo 211498606 © Petr Kahanek | Dreamstime.com