UNESCO’s Time

The World Heritage List citation that accepted the Friday mosque in Isfahan in 2012 contains the following text:

Located in the historic centre of Isfahan, the Masjed-e Jāmé (‘Friday mosque’) can be seen as a stunning illustration of the evolution of mosque architecture over twelve centuries, starting in AD 841. It is the oldest preserved edifice of its type in Iran and a prototype for later mosque designs throughout Central Asia. The complex, covering more than 20,000 m2, is also the first Islamic building that adapted the four-courtyard layout of Sassanid palaces to Islamic religious architecture. Its double-shelled ribbed domes represent an architectural innovation that inspired builders throughout the region. The site also features remarkable decorative details representative of stylistic developments over more than a thousand years of Islamic art (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1397/).

According to this description, the Friday mosque’s value rests in the following characteristics: it links Sassanid and Islamic architectures, it should be considered a model for later monuments, and its ongoing construction and varied styles of decoration symptomize cultural and architectural evolution. The words I have italicized index the temporal ideology implicit in UNESCO’s judgments.

The most important element of the UNESCO citation is that it points to time being a structure external to the monument being judged. That is, the experts are working with a certain vision of positively valued progress of time (evolution from Sassanid to early Islamic to later buildings in Central Asia). The mosque counts as universal heritage because it exemplifies this ideology of time. If what we observe in it could not be correlated with the implicit timeline, it would presumably count as local rather than universal heritage. The mosque’s universal value resides in the fact that it both affirms an existing authoritative temporality and contains rich evidence to reinforce it.

clocks

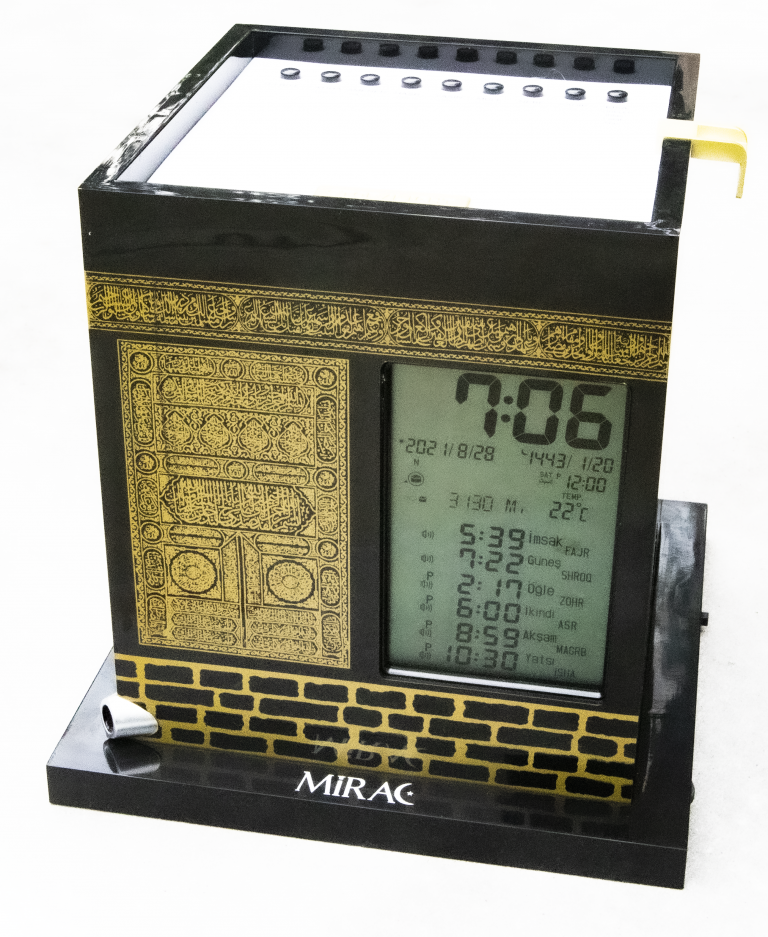

The massive clock on top of a skyscraper that has loomed over the Ka’ba in Mecca since 2010 and is meant to compete with other iconic markers of global time such as Big Ben in London.

SOURCE

Photo 151689637 © Ahmad Faizal Yahya | Dreamstime.com

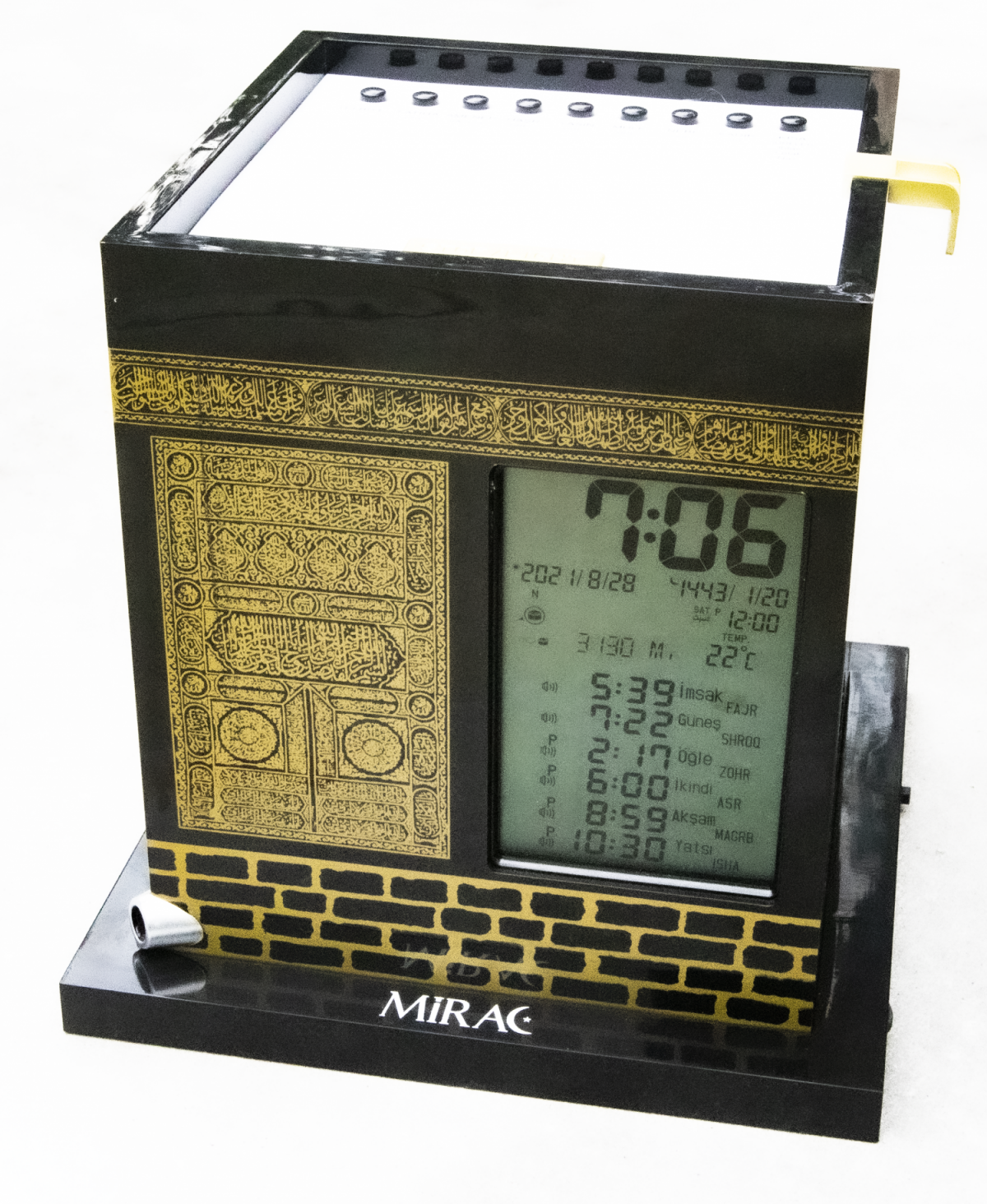

A clock in the shape of the Ka’ba that plays the call to prayer, coordinating between global time (in Hijri and Gregorian calendars) and local times in a city for the five daily prayers.

SOURCE

Photo © Shahzad Bashir (2021)

Go to next slide

Go to next slide

One striking aspect of the UNESCO valorization is that it contains no reference whatsoever to the human actors who created the monument and have continued to augment it for more than a thousand years. Consider, for example, the citation in comparison with the stack of three temporalities found in the mihrab I discuss in the section “Events and Narratives” in this chapter: the monument’s relationship to Prophet Muhammad’s sayings, messianic expectations of Twelver Shi’i Muslims, and particular ambitions of a Mongol king and his ministers. The same goes for the extensive imbrication of the notion of paradise into Isfahan whose characteristics I explore through local histories (“Tropes”), a universal chronicle (“Politics”), and the story of a miracle that cured a woman in the nineteenth century (“Life Stories”). Quite remarkably, then, time as lived in and around the Friday mosque in Isfahan for centuries is irrelevant in the UNESCO perspective.

It needs emphasis that the contrast between temporalities is not keyed to an Islamic insider-outside dynamic. The issue is not that Muslims have a certain view of time and the modern experts who run UNESCO have another. As discussed throughout this book, premodern Muslims held any number of different views on time, some of which could be in radical opposition to that of other Muslims. Moreover, for many modern Muslims, the UNESCO view of time is more intuitive and valuable than what may be found in old texts and buildings. UNESCO’s own evaluations of a site such as the Friday mosque involved considering the views of many Muslims. Indeed, contemporaneous to us, Muslims have been invested heavily in creating distinctly modern regimes of time meant to compete within the economy of modern global time rather than trying to subvert it via reference to ancient matters. There is, then, no universal “Islamic time” out there that can be invoked to make sense of monuments in Isfahan.

By pointing to what is missing in the UNESCO citation, I am not claiming that a single other perspective would somehow be better. Both here and throughout this book, I emphasize the multiplicity of temporal frames that matter for interpreting evidence pertaining to Islam. When it comes to temporality, variability is our greatest asset for creating compelling narratives about the Islamic past.