The story I have told occurs in the middle of a work dedicated to Isfahan completed in 1885. Its author, Muhammad Mahdi b. Muhammad Riza Isfahani, was well versed in earlier literature pertinent to the topic and relies also on his own travels within Iran as well as to Bombay, British India, to create a picture of the city. The miraculous incident is placed strategically within the work, at the end of the fifth chapter that is dedicated to a summary history of Isfahan from origins to the author’s time. It acts as a punctuation, due both to its placement and the emotional intensity of the way the story is told.

Throughout the telling, the author takes pains to substantiate details such as the precise date and place when the event occurred, names and professions of the male participants, and details of the way observers reacted to the event. This commitment to evidentiary particulars was likely motivated by his fear of being proclaimed a fraud. He indicates, at the very beginning of the account, that he wrote in an age where apostates and doubters of religious truths were inexplicably ascendant.

Amid all his effort to provide precise documentation, the vision at the center of the event is a mystery shared only between the woman and Husayn, her long-dead visionary benefactor. The narrative of the vision is, however, critical to the author’s purpose to be regarded as a reliable reporter on the city’s life. The event’s extraordinary quality does double duty: it ratifies him as a faithful believer in holy persons’ ability for miraculous intervention while also allowing him to stress his credentials as a historian driven by material facts.

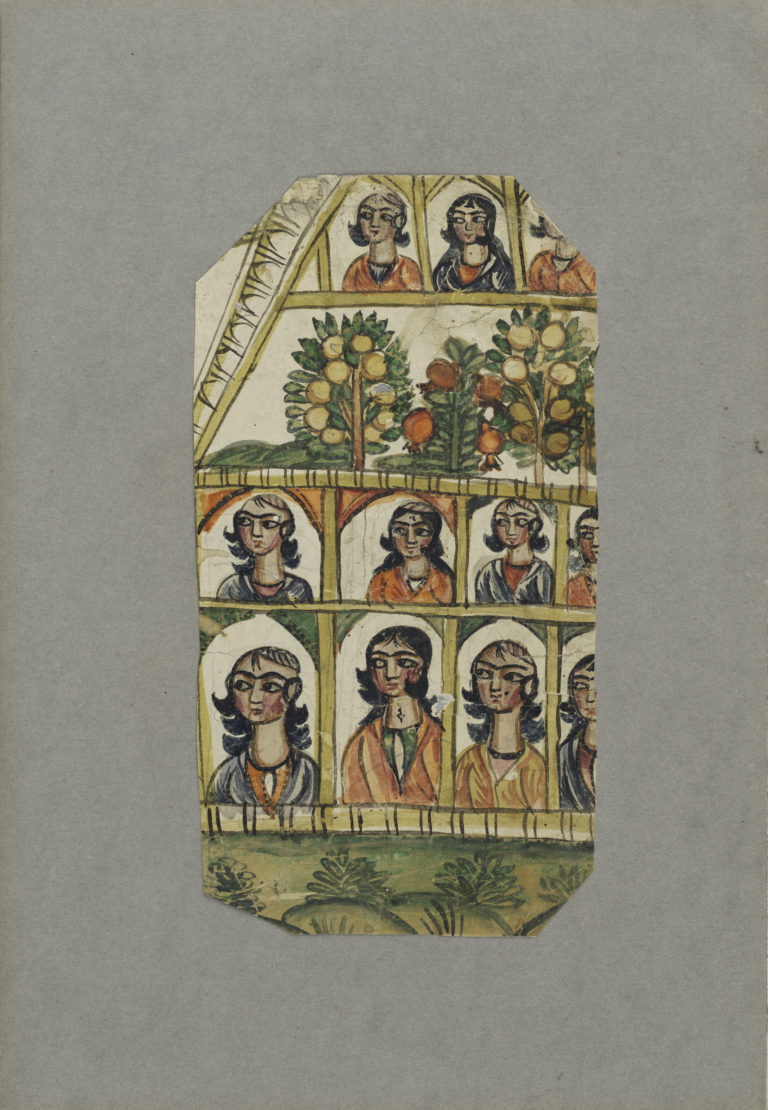

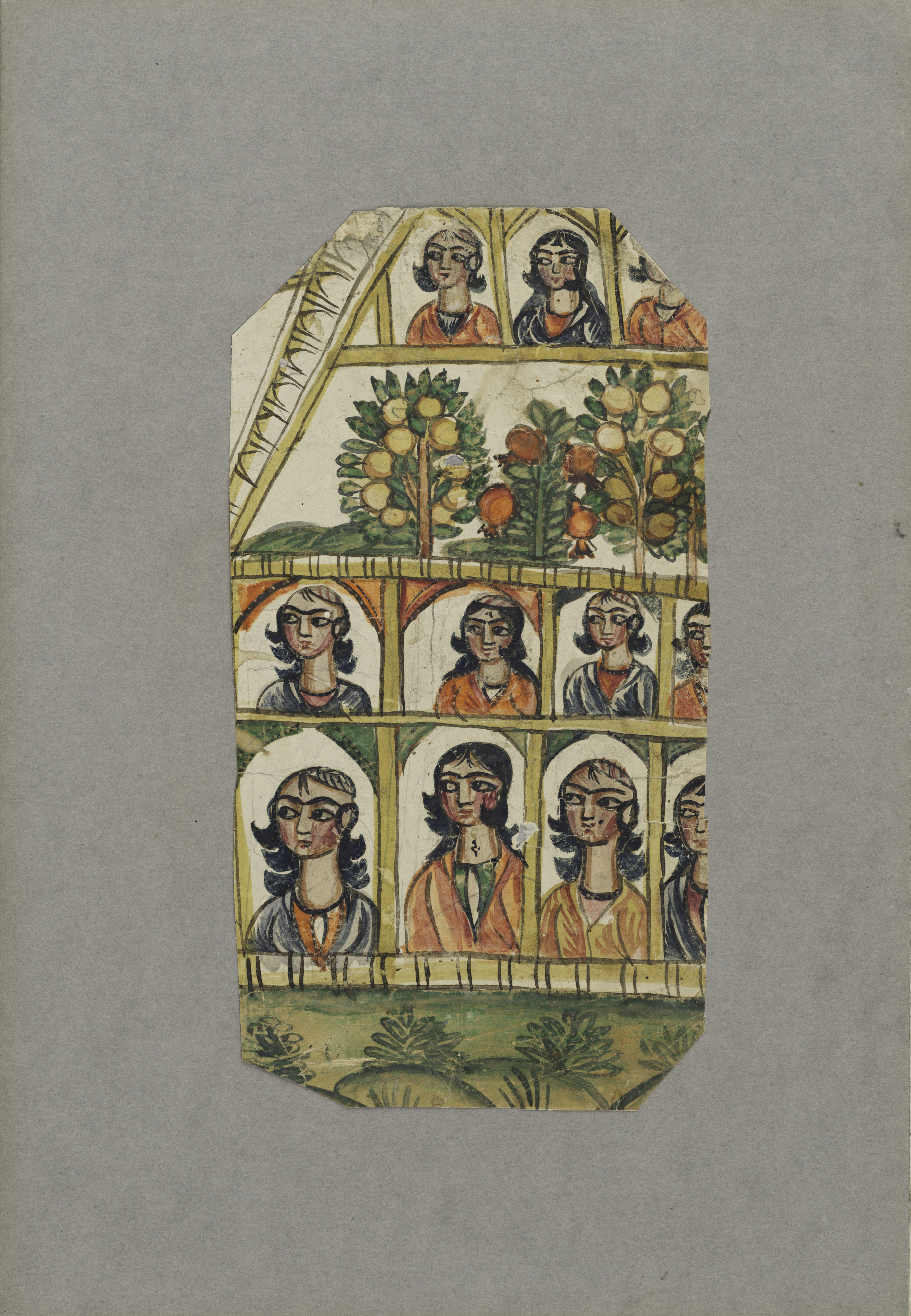

This story from the archive relevant for Isfahan is instructive for appreciating time as a manufactured construct within narratives about the past. Present within temporality, we can see here elements of emotion, sympathy, anguish, precedent, faith, doubt, ethics, and social normativity. The train of events that gets us to the miracle begins by the fact of comparability of sorrows. In the brother-in-law’s intentions, the woman connects her sorrow to Husayn’s even more intense, cosmic suffering so that the latter becomes a redemptive balm on her affliction. To know the past in the form of Husayn’s story is then a palliating imperative, here actuated by a highly emotive literary representation, called a paradise, that triggers the miracle.

The author of Husayn’s tale and its reciter—those who manufacture and perform the past—make the story real, accessible, and useful for people in need such as the afflicted woman. Husayn being shown moved by her pleas indicates a different aspect of the process: the martyrdom narrative keeps the great man, long dead, alive to the existential needs of those in the material world.

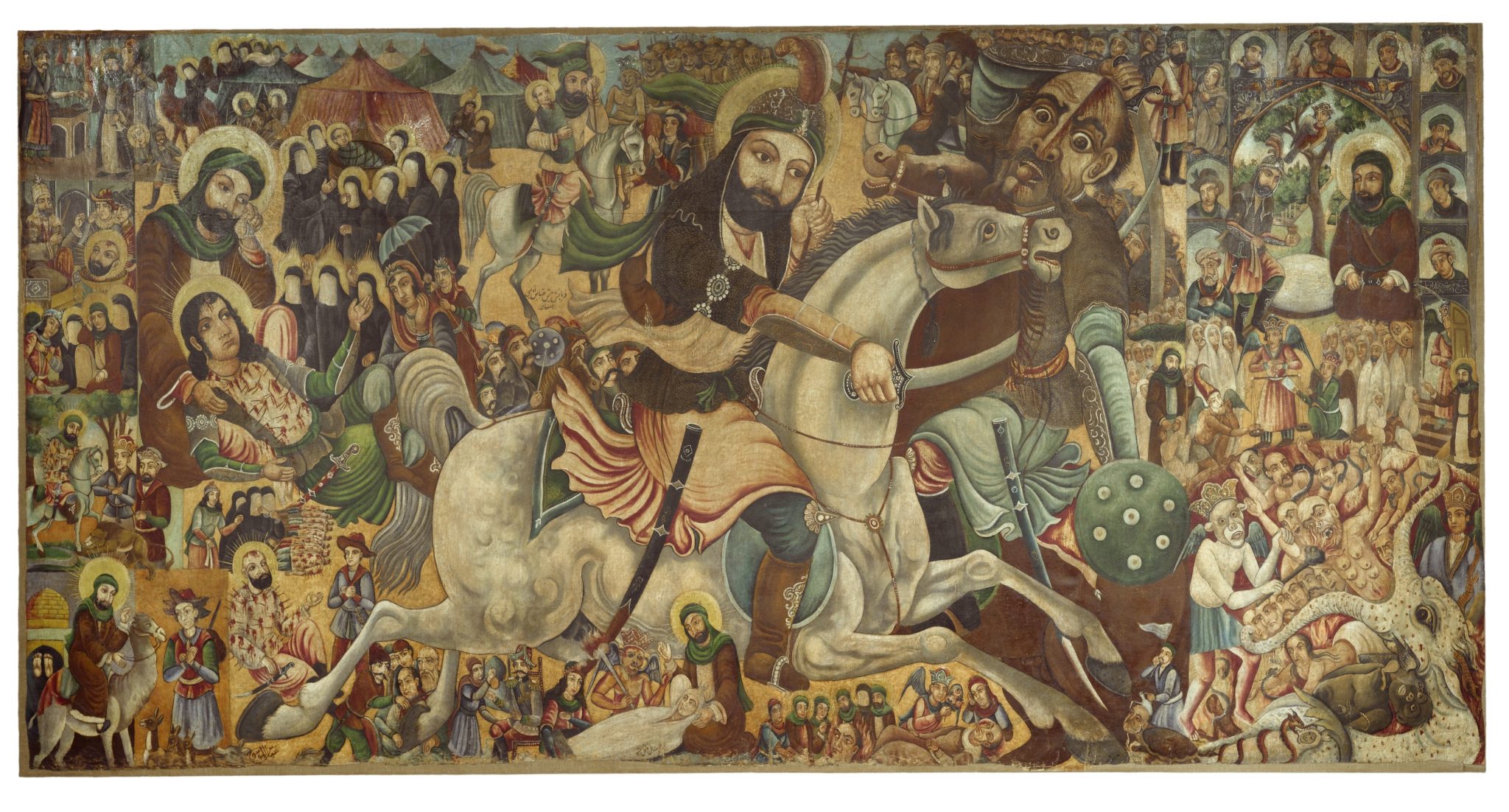

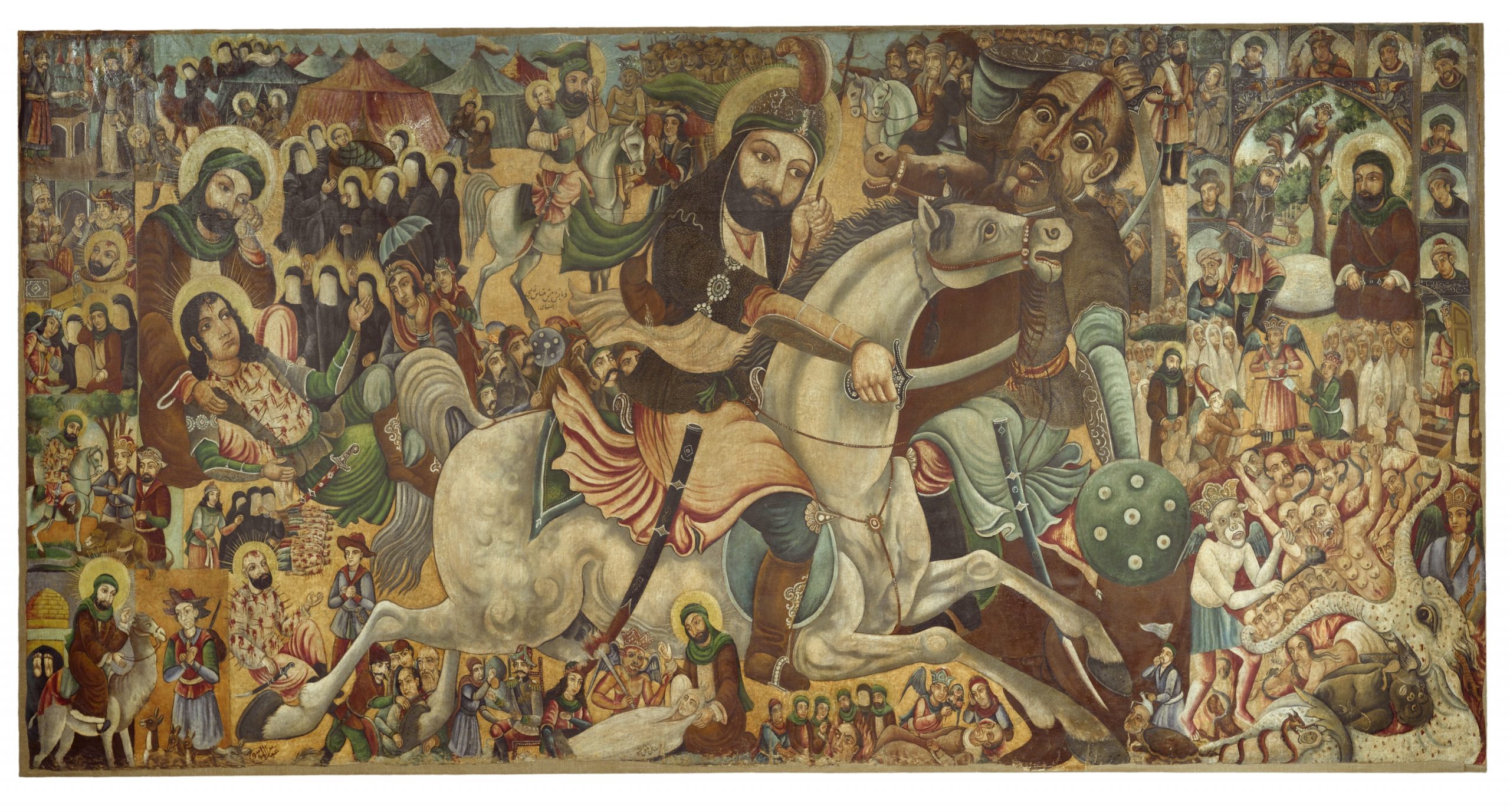

Image describing the significance of Husayn’s death posted on the official website of Iran’s Supreme Guide Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (2018).

Source

Image describing the significance of Husayn’s death posted on the official website of Iran’s Supreme Guide Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (2018).

SOURCE

http://english.khamenei.ir/d/2018/09/18/0/13916.jpg

The story of Husayn’s death is a prominent Islamic leitmotif with a vast footprint in Islamic literary materials. It is a tale I turn to several times in this book. The story’s value in the present context depends on its repetitious and ritualized performance. Both the reciter and the hearers know the story already; its narration here does not indicate a transmission of information. Rather, its vocal representation within the charged environment of the woman’s state activates its power and makes Husayn available in the moment. The past matters, profoundly, in ways that are personal and emotional. But in any given context, its deepest traction pertains to narratives that repeat the stories, morals, ideas, and sympathies already present within an audience or readership.

The extraordinary event described in the miracle story also works to convey religious and social conformity to its intended audience. The story exalts Husayn as an exemplary person whose selfless actions committed centuries ago conformed to the cosmic role that had been preordained for him. This message is at the heart of the literary work whose recital led to the miracle. Through voice and touch experienced during the visionary encounter, Husayn’s power is conveyed to the woman, crossing not only differences of time and space but also the polarity of gender.

The healed woman is presented as celebrated and powerful. But she acts only among women and also becomes wife to a man of prestige and mother to his child. Her miraculous healing and subsequent power serve to affirm the class and gender norms of the surrounding society. The epic of Husayn, conjoined to the story of an exceptional event, works to reinforce dominant social codes of the society where the narrative was produced.

The miracle that forms the keystone of the narrative I have described has functions parallel to the paradise complex I discuss in the “Tropes” section of this chapter. They signify two different types of tropological deployments common within temporal articulations. Their unreality is an aporia that provides greater truth to the experienced descriptions of time and space that surround them in the narratives where they occur. Paradise signifies idealized experience, keyed to unchanging time and space, that acts as a reference point for valorizing ordinary times and spaces.

The miracle is a kind of temporal short-circuiting that breaks the ordinary chain of causality and sutures times and events in a way contrary to rules that govern narrative time. The miracle is an exception that both confirms the unexceptional and provides the possibility of escape from ordinary demands of believability. Attending to tropological issues such as using paradise to describe earthly reality attunes us to flavors that go into the construction of time.