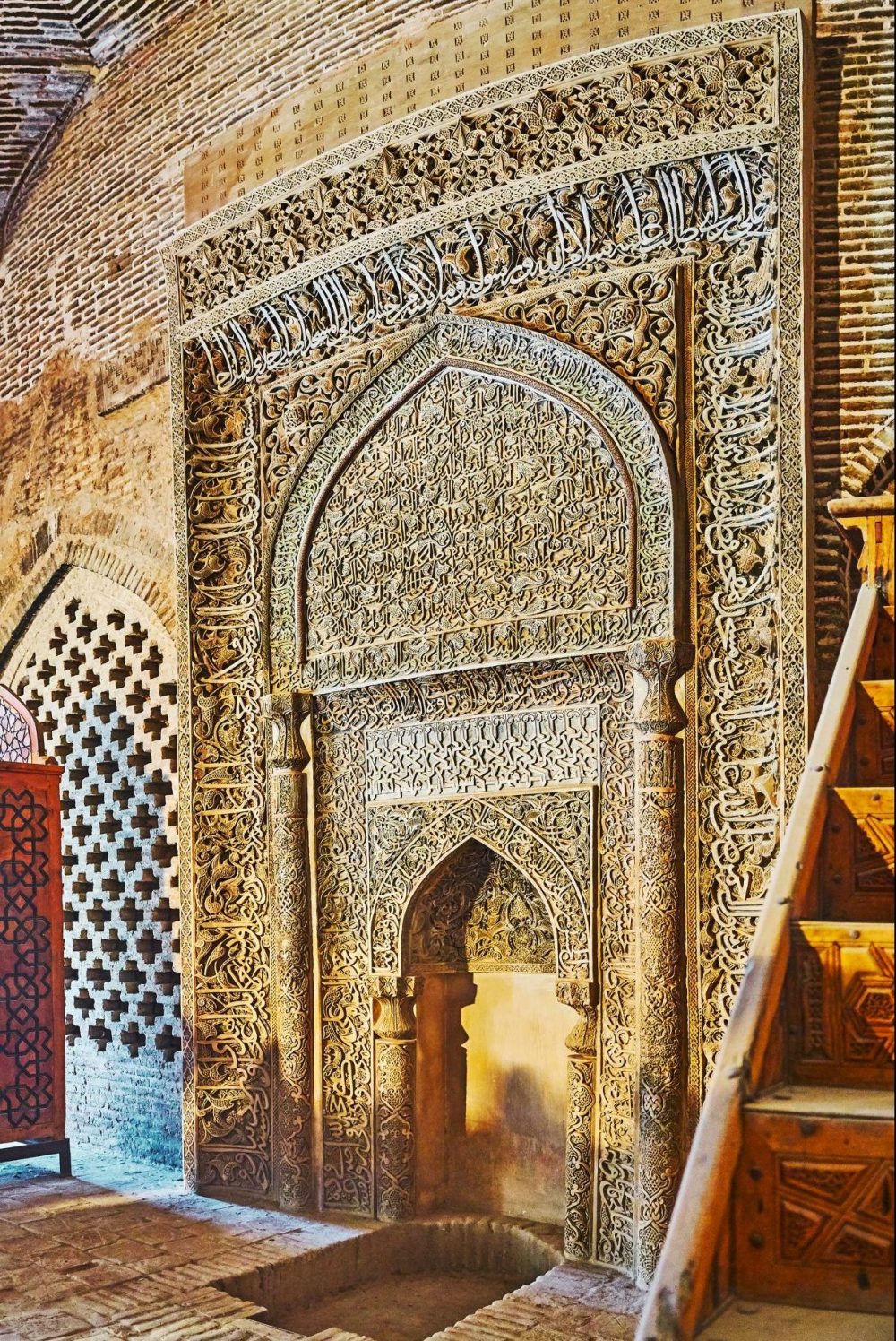

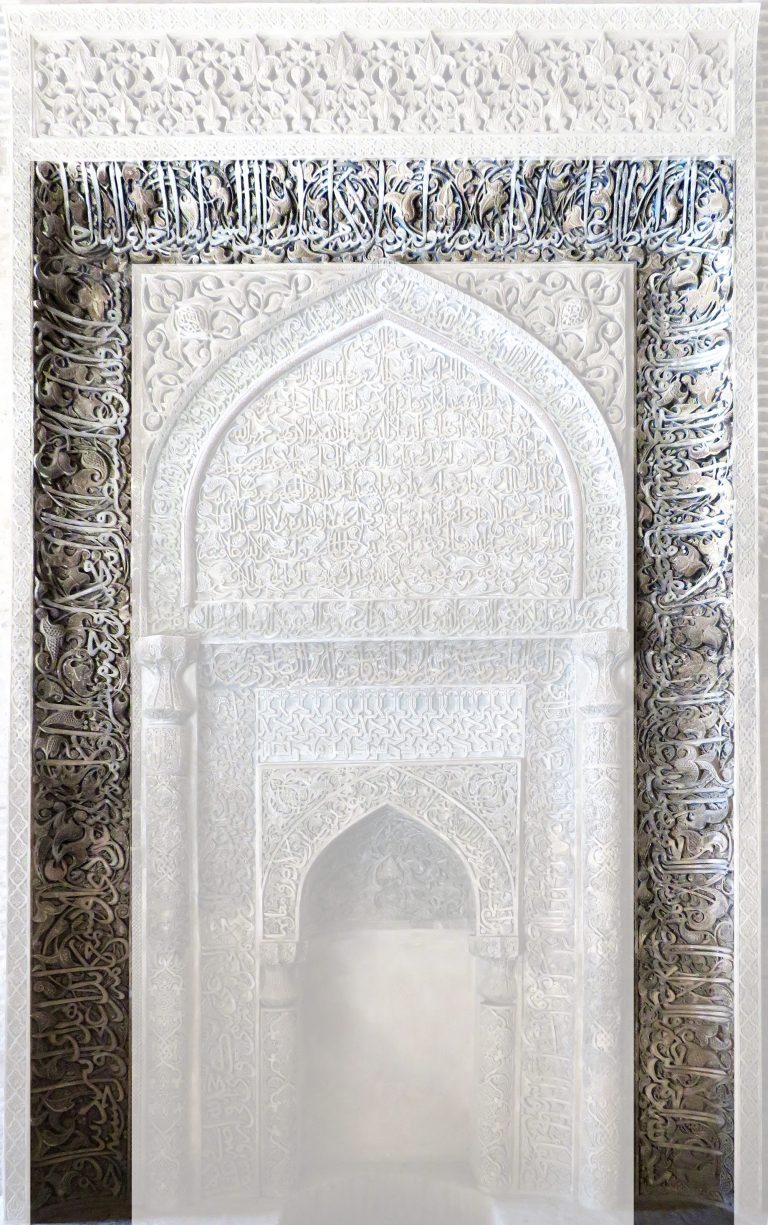

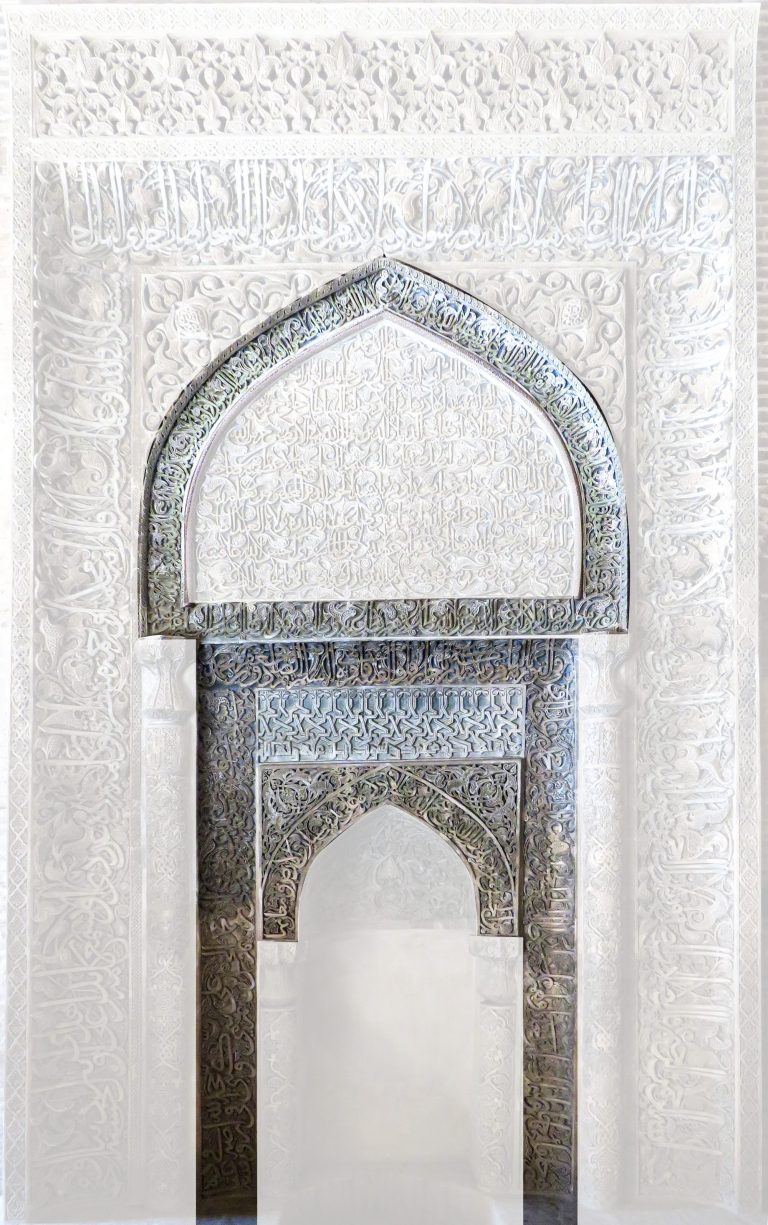

The word time and its equivalents in other languages encompasses two meanings that seem contradictory on first encounter. For one, we use it to refer to an event, for example, the occasion (or time) when I experienced the Friday mosque in Isfahan described in another section of this chapter. Time as event draws a boundary around a set of experiences within the flow that I identify as my life. Put into a larger frame of reference, the same principle can apply to my whole life, a lifetime, that binds me within the accidents of birth and death and identifies experiences peculiar to me in comparison with other beings.

Time in the sense of event can be scaled to any level—from a second to millennia—as long as there is a principle that provides internal coherence leading to a boundary around a set of ideas or experiences. Both psychologically and as a matter of description in historiographical representation, time as event must be “meaningful,” although here, too, the significance of the event can vary greatly. My visit to the mosque in Isfahan was a momentous event and has continued to affect me since 2012. A trip to the grocery store in my neighborhood is also an event although of a very different magnitude in meaning because of its limited effects. When describing the past, we appraise received information to select those matters that can be organized into events significant for the overall perspective we wish to convey.

In addition to its meaning as event, the word time refers also to the abstraction that stands behind the fact of incessant variation in the material world. Invisible in itself, time in this sense is detectable through reference to change in “the space in which humans live and to the nature within which they are embedded, be it the system of planets by which clocks and calendars are regulated, or the succession of biological generations as it is expressed in the social and political realm” (Koselleck, “Time and History,” 102).

Described in isolation, time as event and time as material change seem to stretch temporality to opposite ends. The two meanings are, however, interdependent and mutually mutable notions, each being the condition of possibility for the other. Time as change is “eventful” since positing the difference that creates the sense of variation is predicated on a comparison between two states of stability (i.e., events). And on the opposite side, change must be taken as a fact to create the boundaries that characterize a certain set as the definition of time as event. The separation, yet interdependence, of time as change and event explain why representations of time can vary greatly without causing the failure of logic.

Understandings of change in the past can be altered radically through the discovery or invention of a new event. In this instance, a newly posited bounded time can transform our understanding of time’s flow. For example, over the last century, efforts to recover women’s activities and voices have caused great change in the understanding of the human past as a totality. Conversely, transformation in the way we perceive change can alter our sense of events. Once the male-centeredness of historical representation is removed, what may have been considered an event pertaining to a unique woman may become transformed into a wide social pattern. Once women become visible in history, we “discover” them as actors in all contexts rather than seeing their presence as an exception.

The interdependency between time as change and event has another critical function as well: each acts as a check upon the free transformation of the other. Time as flow is limited by the contents of what can be accepted as events. A claim about change over a period requires the details of events as its building blocks. Conversely, the discovery, creation, or acknowledgment of a new event is meaningful when it fits into an existing flow. Occurrences that do not do this are nonevents until they become parts of a narrative.

Continuing with the example of women’s greater historical visibility, to claim women’s importance in history requires that we document events where this is evidently the case. And the discovery of an event where a woman acts in a certain way becomes meaningful through reference to a larger narrative. Stories of women who were regarded as great religious scholars, for instance, disrupt the notion that formal intellectual production in a society has been limited to men. But valuing such a discovery is predicated on an overall view of the past in which scholarly activity is understood as a positive aspect of social existence. In a situation where this is not accepted as an axiom, documenting instances of women as scholars would have little social resonance.

Both time as change and time as event are susceptible to mutation, although this requires conjunction between the two. This means that representations of the past can modulate along multiple axes since these are formed by combining the two notions of time. For this to happen in a given context, some aspects of understanding must be held as positively true, or factual, while other elements are treated as variable. Of course, what is taken as truth in one situation can be challenged in another, based on taking a different element within the situation as fact and considering what was thought true in the first case as variable.

Ultimately, this means that identical basic observations can be used to create any number of different representations of past time, depending on investments held by the interpreters. The simultaneous differentiation and interconnection between time as change and time as event helps us make sense of a basic fact: experiences that can be shown to have been shared between multiple witnesses can nevertheless be documented and represented in radically different ways.