Juvayni and the Moral Framing of History

The Tarikh-i Jahangushay of ‘Ata-Malik Juvayni contains a story that is helpful to understand the circumstances of the Mongol empire. It goes to the time of the death of Ögedei Khan (d. 1241), Genghis Khan’s immediate successor, amid rivalry within members of the ruling family. As the contenders awaited the council to determine the next ruler (quriltai), Töregene Khatun, one of Ögedei’s wives, was designated the caretaker. While a part of her authority came from being the mother of Ögedei’s oldest children, she had political ambitions of her own and embarked on determined action to form a faction among the ruling elite. This brought her into conflict with her own sons, including Güyük Khan (d. 1248), the eldest, who was eventually installed as the empire’s ruler in 1246.

Juvayni tells us that during the short period Töregene Khatun was the empire’s (contested) leader (1241–1246) based in Mongolia, she delegated much of her authority to a woman named Fatima Khatun. This second, very powerful woman in the empire had an unusual path to gaining authority. She had been captured near the city of Mashhad in Iran during the Mongol conquests under Genghis Khan. Given as a slave to Töregene Khatun, she had risen rapidly to a place of companionship and trust due to her intelligence and mental agility. Installed into a position of great authority, she was sought after by the population, especially by the leaders and sayyids of her native region who wished to influence imperial policy. It was said that she was herself a sayyid, a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad.

Fatima’s prominence led to a charge of sorcery by Köten Khan, one of Töregene’s sons, who had become sick. He told his brother Güyük that should something happen to him, Fatima Khatun should be held responsible. Shortly thereafter, Köten died. Güyük’s courtiers, who were opposed to Töregene and Fatima, incited Güyük to ask his mother to send Fatima to him. Töregene resisted for a while but was eventually compelled to give her up. Fatima was then tortured brutally for days until she confessed to the charges against her. They then sewed up the upper and lower entry points into her body, put her in a felt, and threw her into the river near Samarkand. Everyone connected to her, including those from Mashhad who claimed to be related to her, was also subjected to severe interrogation. Juvayni commemorates the story with a verse addressed to God:

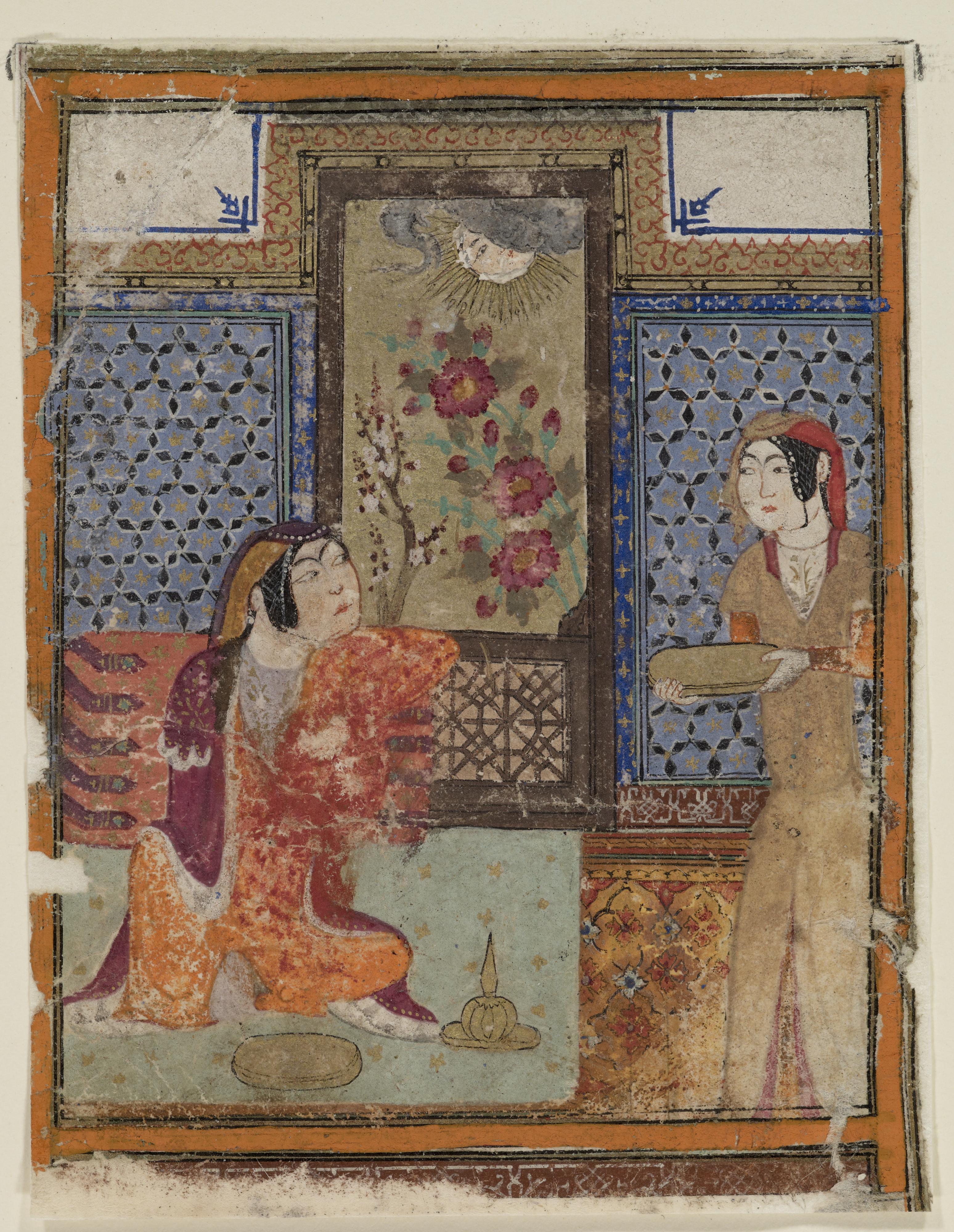

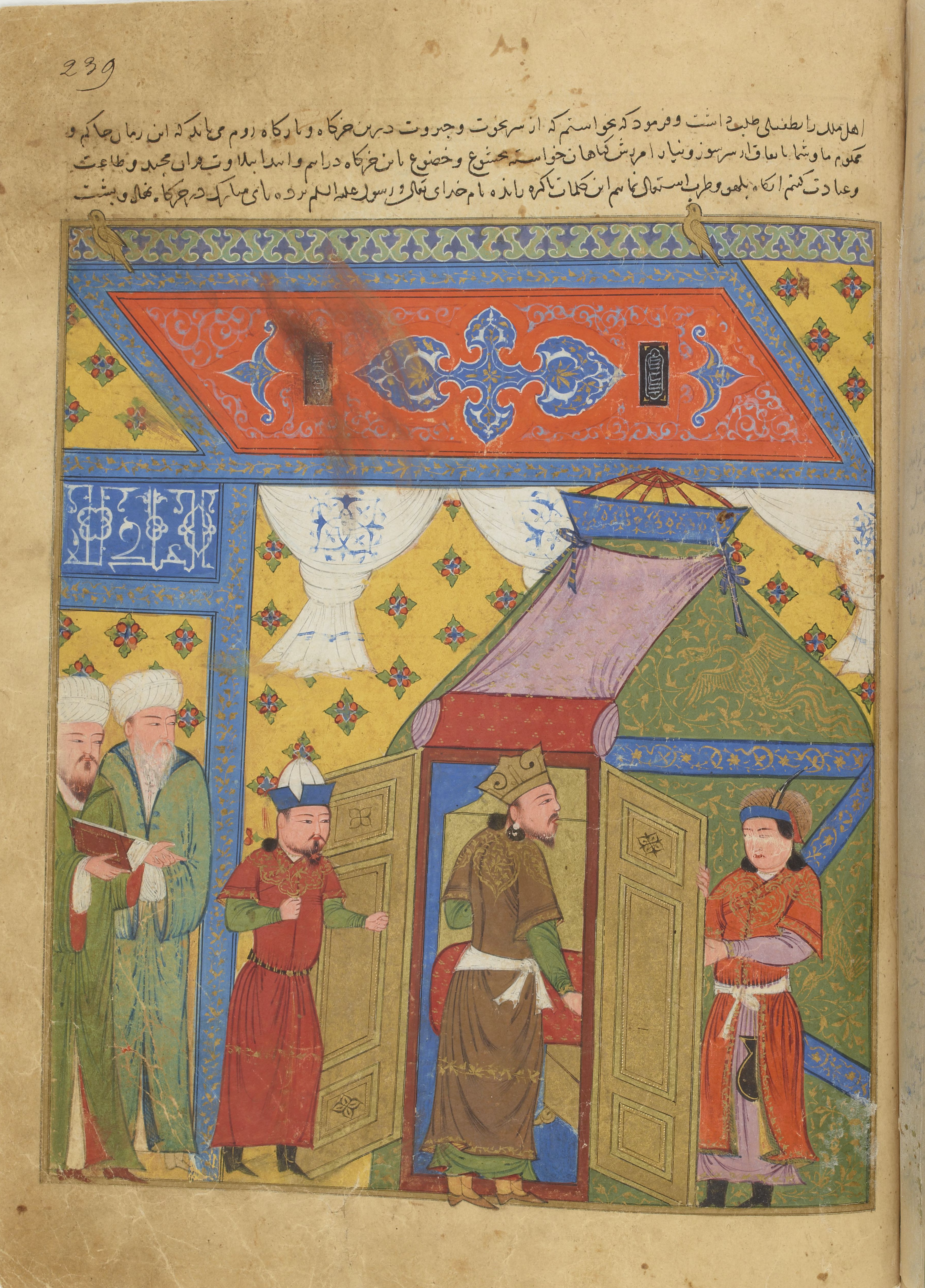

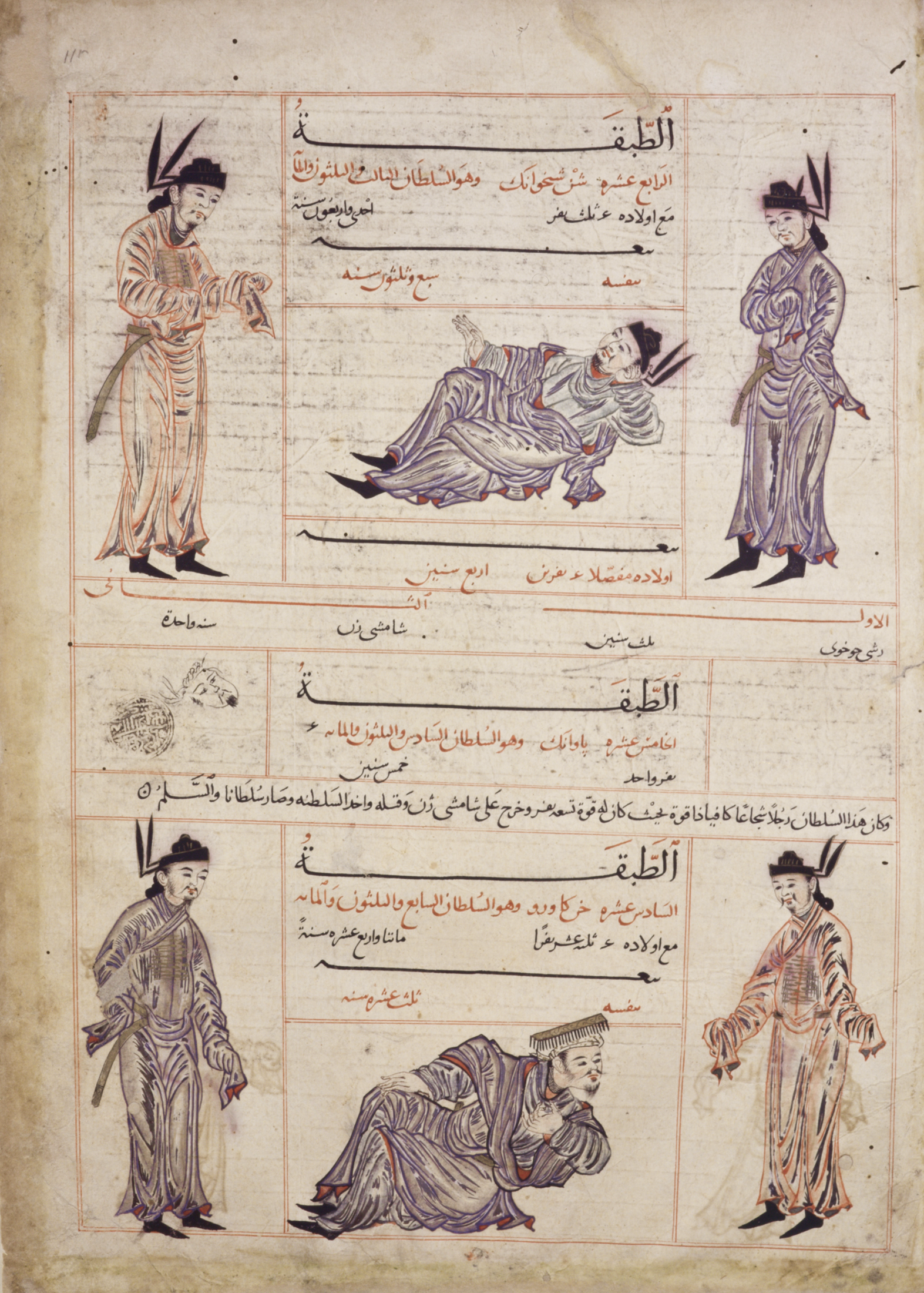

Depiction of Mongol women in a manuscript fragment (ca. 1300).

Source

Depiction of Mongol women in a manuscript fragment (ca. 1300).

SOURCE

Diez Album, Staatsbibliothek, Berlin, fol. 71, S. 18, no. 2

You bring someone up and give them kingship.

Then You send them to the river to the fishes.

(Juvayni, Tarikh-i Jahangushay, 302–303)

This story provides a sense for life’s precarity under Mongol rule. Conquests unleashed by Genghis Khan and his descendants caused tremendous bloodshed and carried large numbers of people into slavery and severe dislocation from their homelands. The brutality of Fatima Khatun’s end has parallels in dozens of other scenes of torture and collective punishment recorded by Juvayni and other reporters. Yet, it is also noteworthy that in this sociopolitical setting, a Muslim woman captured and enslaved at one point could later rise to a position of great power. Moreover, her prominence did not depend on status conferred through marriage or motherhood.

Fatima’s story as it is available from Juvayni and later authors is too fragmented for us to get the full picture. At a minimum, two things seem to have been crucial to her rise: personal capability and a non-Mongol high social status by birth. For Fatima Khatun to have made decisions about the empire’s financial concerns implies aptitude, training, and sociopolitical acumen. Her reconnection to her sayyid relatives despite enslavement speaks to the continuation of patterns of Muslim social prestige after the Mongol conquest. In fact, her brief authority and the ability to help her relatives indicate established Muslim hierarchies seeping into Mongol structures of power. Her spectacular demise highlights the fragility of success under the prevailing conditions: access allowed by the social setup was easily overturned, with dire consequences.

Juvayni’s account of Fatima Khatun is presented in a neutral voice, although one imagines that his personal background as a Muslim bureaucrat in the Mongol empire, hailing from a celebrated family, may have induced him to be sympathetic. Like her, he was a close confidant to some Mongol rulers while being despised by others. While his access to Mongol courts was the documentary bedrock for what he related in his chronicle, his administrative job did not require that he write history. The work’s introduction provides an explanation of its overall purpose, taking into account the fact that it was written under the brutalizing circumstances we can see in the story of Fatima Khatun.

At the broadest level, Juvayni’s own explanation for his work is that he sought meaning in the events he had seen come to pass. His ultimate appeal is to God’s plan for the universe, which must include some purpose behind all the devastation and dislocations (118). Reflecting on this issue, he provides both religious and worldly reasons for understanding the Mongol takeover as an event whose purpose could be discerned.

On the religious side, the Mongols’ arrival had expanded the presence of Islamic beliefs and practices in the world, thereby propelling the religion’s ultimate universal triumph. Before their expansion into Muslim territories, the Mongols worshipped false gods, as had been the case among Arabs before Muhammad. By becoming acquainted with Muslims, they had now started to change through gradually converting to Islam. As proof that this process had begun, he states that he had heard from the Mongols’ old priests that the presence of Muslims had made their idols angry. They had stopped talking to the priests as they used to do in days of old (120).

If the Mongol expansion was to be seen as opening the world to Islam, then the fate of Islam would seem to have an inverse relationship with the lives of those who were already Muslim. In this understanding of the divine plan, God had mandated the pillage of Muslim lives and livelihoods as a part of his ultimate purpose. Acknowledging this consequence of his argument, Juvayni indicates that even this could be seen as something positive. Muslims who had died at the hands of the Mongols had achieved martyrdom, an assured way to accede to paradise in life after death. And those who had survived had received the most profound lesson, to invest in religious rather than worldly pursuits. Their suffering could then be read as a goad toward salvation (120).

Mongol victories had provided a worldly lesson as well, namely in the form of teaching Muslims, by the Mongols’ example, how a strong, well-organized force operates in unison. The Mongols’ actions on this score were the opposite of the situation of the Abbasid caliphs and their retinue who were militarily weak and riven with internal conflicts. It was significant too that the Mongols did not discriminate on the basis of religion—their severity and indulgences toward others were determined by their worldly purposes irrespective of the opponents’ creed.

The fact that many of them had begun to convert to Islam meant that, gradually, their military advantages would transfer to the side of Islam and they would become instruments for the right religion. They may think that their empire’s formation was their triumph. However, this was actually God’s way for them to be roused from their wayward state to become a bittersweet medicine for Islam’s historical trajectory.

Was Juvayni a venal bureaucrat tasked to justify the depredations of his employers? Or should we take him on his word as a sincere person trying to make sense of his world? These questions have loomed large in modern readings of Juvayni, especially because he was a companion to Hülegü Khan in 1258 when the Mongols sacked Baghdad and put an end to the Abbasid caliphate. Both in scholarship and in popular memory to this day, Hülegü is portrayed as an arch villain responsible for the end of the classical age of Islam. It is true that Juvayni’s narrative lauds Mongol sovereigns and does not condemn their rise in categorical terms, as done by his contemporaries writing in places such as India and Egypt that were outside the Mongol sphere.

But to my reading, it is important to note that Juvayni was concerned to describe and explain the rise of the Mongols but not necessarily to advocate for it. The world he experienced was not a matter of his choice. Inasmuch as it had come to exist, he was, as the chronicler, called upon to explicate it in the context of a providential framing of history. Locating positive possibilities in this situation was an imperative dictated by the belief that God had predetermined Islam as an incontrovertible truth whose ultimate triumph was presaged in Muhammad’s original message. If a lot of Muslims were in distress at a given moment, this fact needed accommodation within an overall triumphalist view of Islam’s future.

Syrian television broadcast a 30-part serial “Hulaku” in 2002. Juvayni is depicted as the narrator writing down the events. In episode 23, the Abbasid caliph is executed (9:00) and Juvayni writes about the devastation of Baghdad (13:30).

The distinction between the past and future of Islam versus that of Muslims hinges also on the fact that, for Juvayni as well as others, not all who proclaimed themselves Muslims were to be treated alike. A very significant proportion of Tarikh-i Jahangushay—in fact, the narrative’s long concluding section that vigorously lauds the Mongols (3:719–851) —is devoted to the defeat of the Nizari Isma’ilis and the destruction of their legendary fortresses such as Alamut (see the section “A Resurrection” in chapter 7). For Sunnis like Juvayni, the Nizaris were a wayward and pernicious form of Islam, worthy of extreme suppression. If this came to happen through the agency of the Mongols, then the invaders were to be seen as the instruments of a just divine intervention in the world.

Juvayni’s chronicle provides the full text of an Epistle of Victory (fathnama), a public announcement sent out after an expedition, that the author had composed for the Mongol court to commemorate the destruction of the Nizaris (3:725–747). Much of this document provides the details of the military conflict, including the purportedly incurably treacherous nature of the Nizaris. Juvayni compares Hülegü’s role in the preservation and propagation of correct Islam to none other than the Prophet Muhammad himself and states the following:

By this victory… the reality of God’s secret pertaining to the rise of Genghis Khan has become apparent and the prudence of the transfer of domains and kingship to the Emperor of the World Mengü Qa’an [Hülegü’s brother, the reigning Mongol sovereign] has become obvious. … With this good news, the zephyr has started to blow and the birds to fly in the air. Saints (awliya) say happy greetings to the prophets’ spirits and the living send congratulations to the dead:

A victory such that heavens’ doors are flung open.

And the earth is displayed in new garments (3:744–745).

Juvayni’s moral judgment on the Mongols was rooted in the perspective that his own faction was the ultimate arbiter of correct Islam. Clearly, his views would not be shared by others, especially the Nizari Ismailis who considered themselves equally good Muslims and would have had to find an alternative rationale for what had befallen them.

The contrast is critical for this book’s argument in that it shows the impossibility of creating a morally univocal history of Islam. For both Juvayni and the Nizaris, the events that came to pass were tied to Islamic ends, albeit they necessitated radically different explanations. In the sphere of moral judgment, history and religious thought were inextricable from each other. Moreover, as shown by the force of the Mongol invasions, moral understandings of the past were perpetually subject to change based on circumstances. While everyone might agree that the past was a morality tale, the lesson to be gained from it could not be the same, whether at a given point or across different periods. Differences of opinion on religious matters triggered conflicting views of the moral framework surrounding understandings of the past and the future. Notably, prospects pertaining to the success of Islam could well necessitate the devastation of some existing Muslim communities.