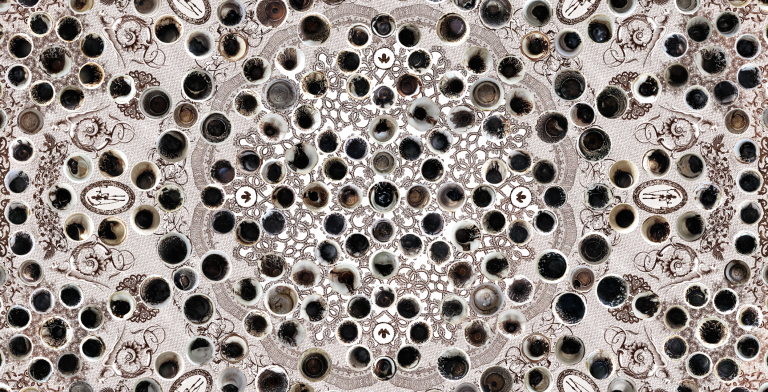

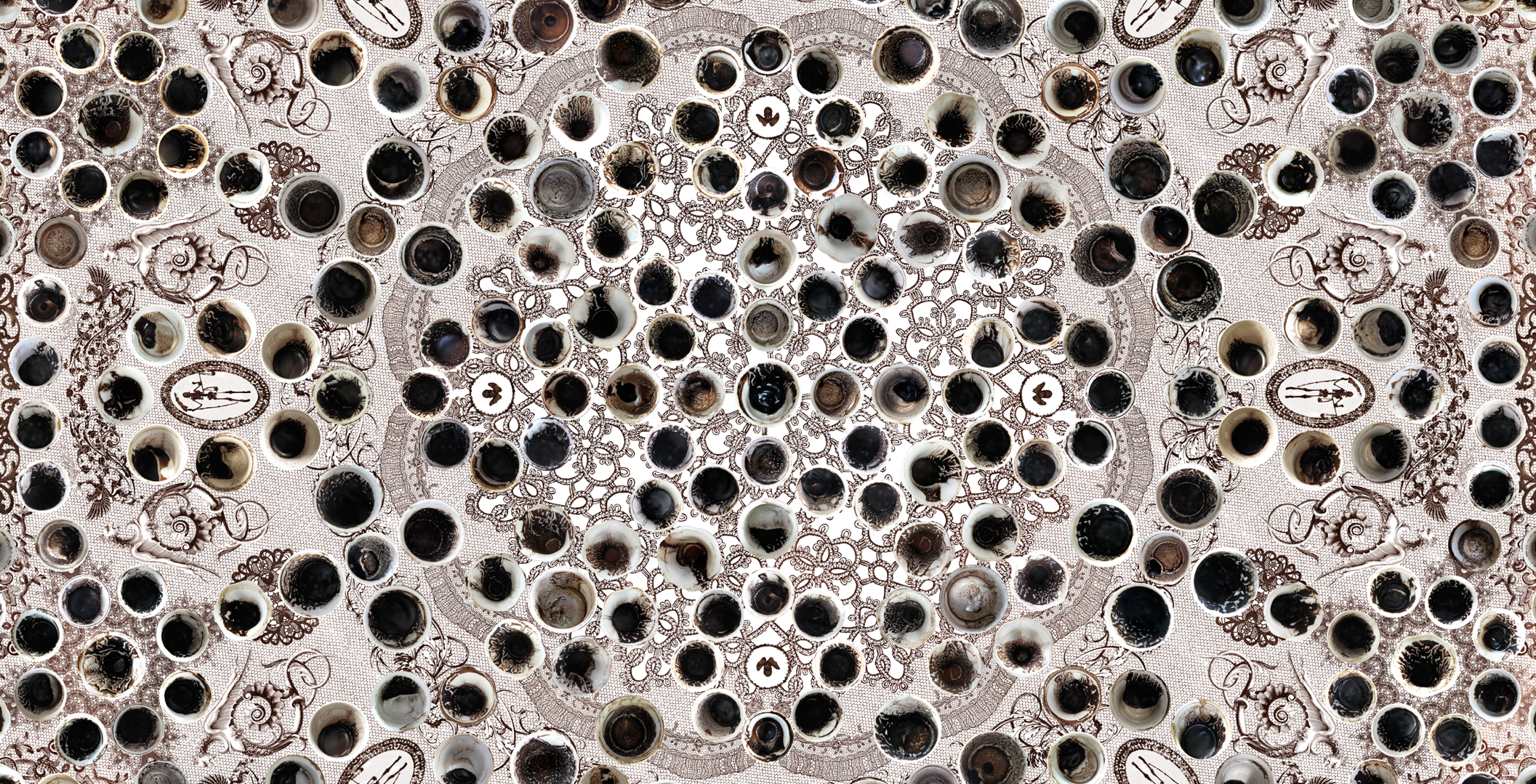

This book’s landing page—its cover, as it were—features Lara Baladi’s digital montage entitled The Rose. This prominent reference to a work of contemporary art is more than an aesthetically pleasing invitation. The Rose is a part of Baladi’s larger project, Diary of the Future, whose deployment of issues pertaining to time matches my analytical perspective. Ruminating on her work has helped me to clarify my ideas and to devise effective ways to communicate them. We are fortunate to have access to Baladi’s own commentary on this theme, although as she has pointed out herself, words often provide an inadequate gloss on art encountered visually. In this section, I first discuss Baladi’s installation entitled The Grave of Time, which is also a part of Diary of the Future, and then present her account of its genesis.

Impressions conveyed visually constitute a parallel and complementary arena to what we can observe about the past via words. This chapter illustrates the independent significance of the visual domain for understanding Islamic contexts by treating a range of examples: the form of a building that has dominated a cityscape for centuries, frescoes in a structure abandoned in the eighth century, paintings in a manuscript, an early twentieth-century photograph, representation of sacred figures in film and television, and a twenty-first century art installation that materializes the past.

In “The Skyline of Istanbul” I treat the impression created by the Süleymaniye mosque built under the supervision of the famous Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan in the sixteenth century. Correlating visual evidence with the narrative of Sinan’s life shows a deliberate emphasis on visual monumentality. The mosque’s form has reverberated out of the building onto paintings, sketches, photographs, and replication of the design the world over. The mosque’s visual impression carries a history unto itself that is an influential signifier of Islam irrespective of how it is interpreted.

The section “Frescoes in the Desert” discusses various evaluations proffered for a building known as Qusayr ‘Amra in the Jordanian desert. I trace the way the building came to the attention of European art historians and why it has proven both fascinating and challenging. The most recent propositions regarding the frescoes found in the building suggest that it can help to decenter textual accounts of the establishment of early Islamic communities out of religious and cultural forms that already existed in the Levant at the time of Islam’s birth. The visual evidence thus projects permeability of religious and other ideas that go unacknowledged in the rhetoric found in textual sources.

A manuscript of a famous Persian chronicle inscribed in the fifteenth century contains a set of exquisite miniature paintings. In “Beautiful Violence” I discuss the fact that the scenes contained in the paintings depict severe violence that was a part of the context in which the manuscript was produced. The manuscript raises questions about modern evaluation of premodern Islamic luxury objects as beautiful art, decontextualized from social and political circumstances. Although produced to glorify political authority, the paintings can be read against the grain as well, registering the pain of bodies being put to torture and death.

A French colonial photograph from early twentieth-century Senegal has become a potent marker of saintly presence and authority in a Sufi Muslim community. In “The Gift of Presence” I discuss the way the saint’s followers have used the photograph as a representation of his essence to creatively make the holy figure a ubiquitous presence in their lives. The case highlights how modern modes of visual reproduction are adapted to create authoritative Islamic pasts.

In “The Missing Image” I concentrate on The Message, a film released in 1976, and the recent Saudi Arabian television series What if He Were among Us to discuss how Muslims have made the Prophet Muhammad available in modern media while observing the interdiction on representing his body. While never showing him, these productions make the Prophet present through creative usage of the camera and an emphasis on the emotions of the people who talk about him as a part of their lives. The cases I highlight invite us to look beyond the notion of Islamic iconophobia to more complex ways in which the visual domain is used to engage the foundational Islamic past.

This book’s landing page contains an image from the work of the multimedia artist Lara Baladi. In “The Grave of Time” I discuss an installation by her of the same name that commemorates her experience of accompanying her father during an illness in Egypt. She photographed coffee cups used by visitors at his bedside and then inverted for purposes of telling the future. Baladi builds elements around the photographs to create a complex structure that physicalizes time. The visual impression of Baladi’s work has inspired many aspects of what is being presented in this book. Her work is a powerful reminder of the fact that sensory domains involving sight, sound, smell, and touch encapsulate temporal dimensions that are not reducible to representation in words.

https://doi.org/10.26300/bdp.bashir.ipf.grave-of-time

Copied to clipboard!A Time Enclosure

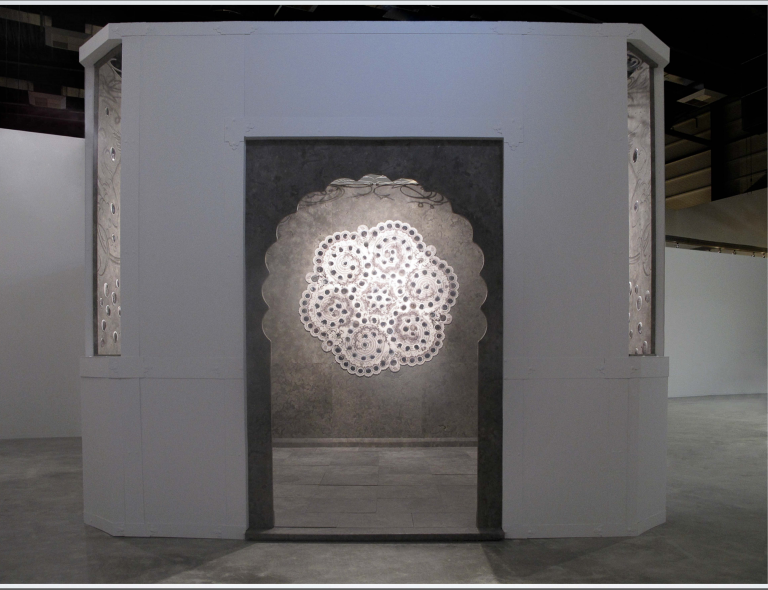

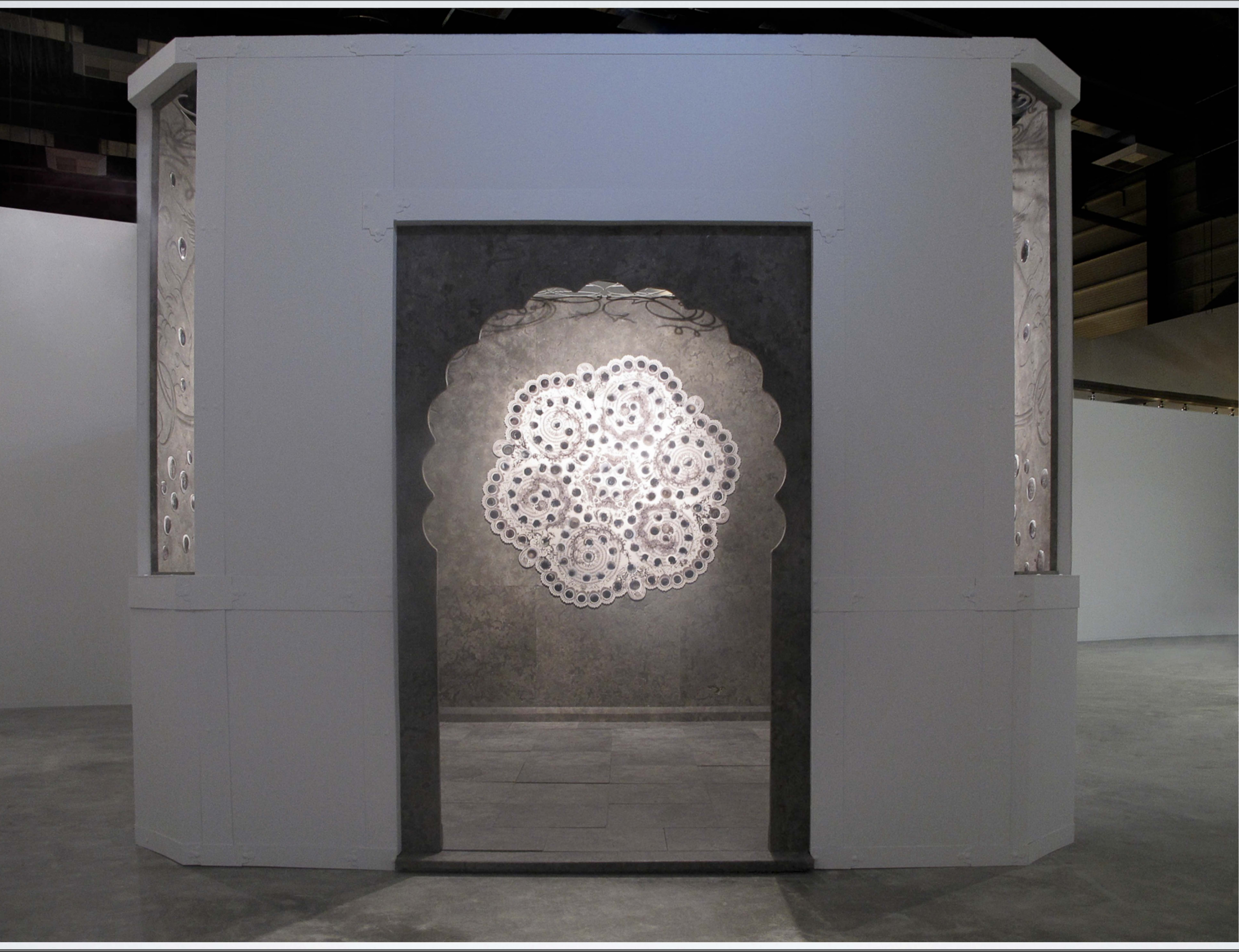

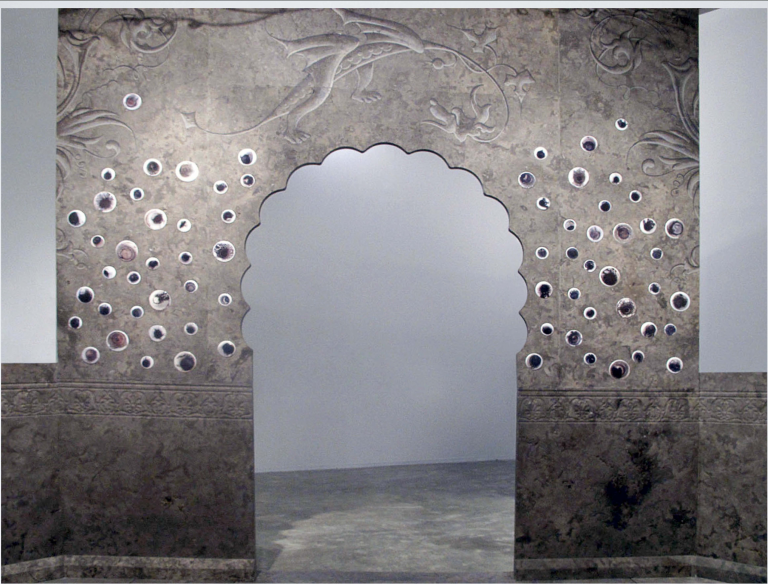

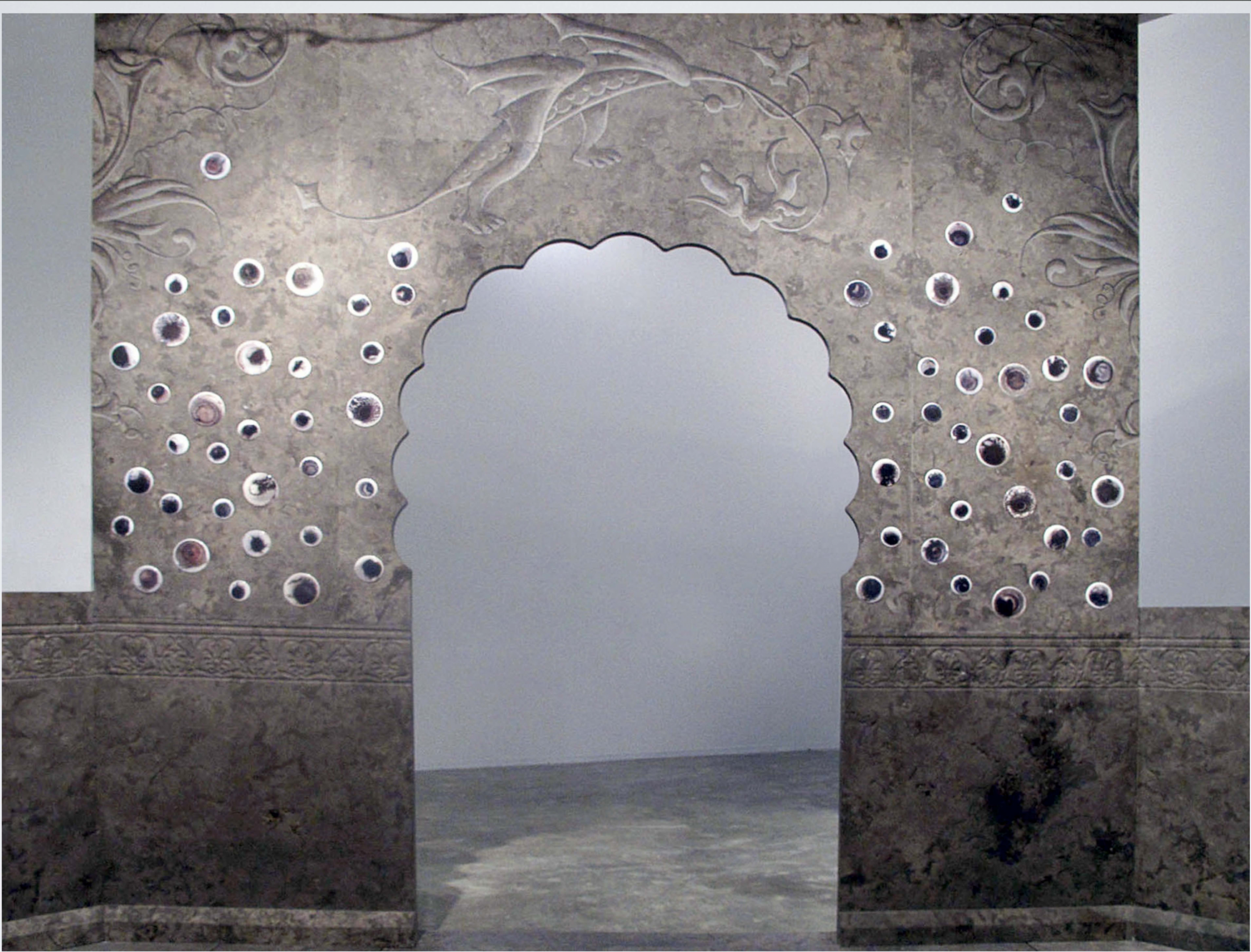

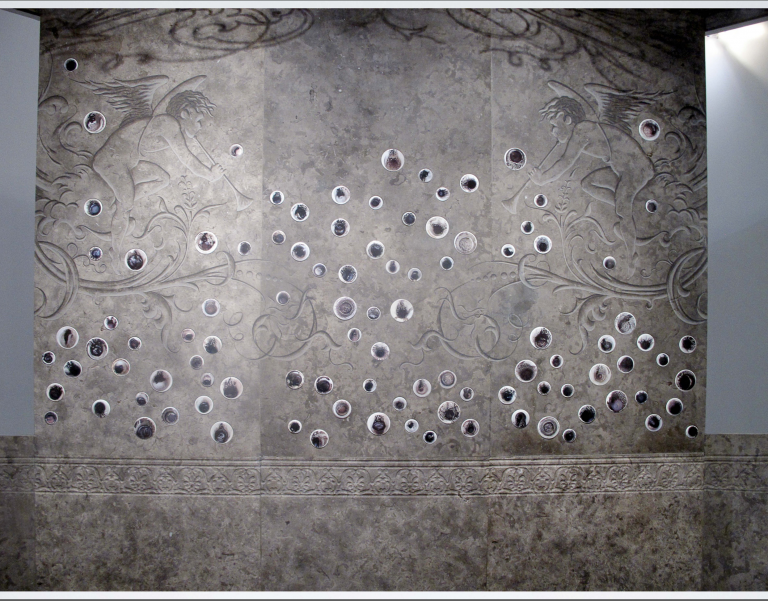

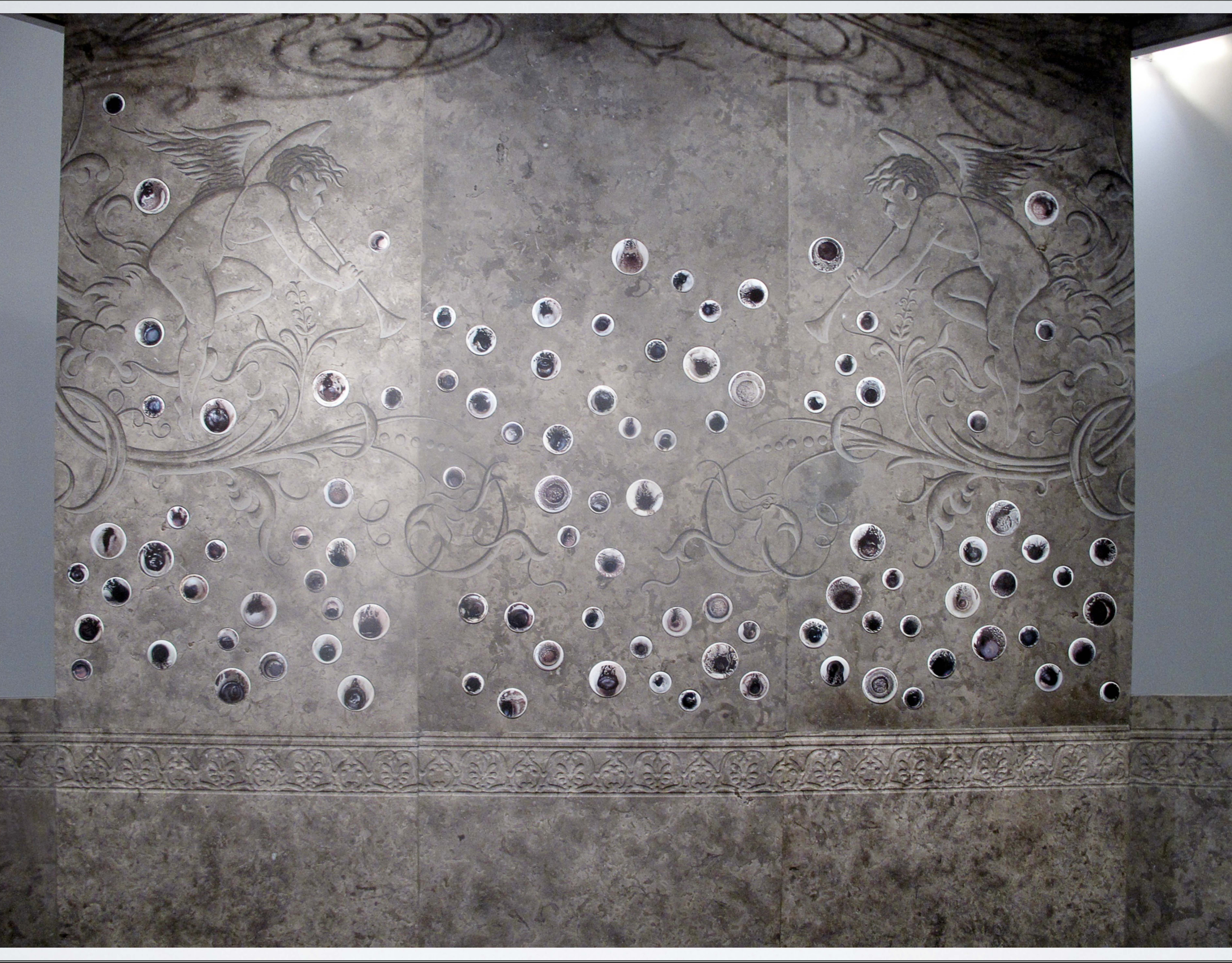

The Grave of Time was an art installation exhibited as part of a larger show at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, Qatar, in 2010. Planned digitally and then manufactured with poured concrete and other materials, the work consisted of a small room with solid walls that had cutouts at the corners. Its ceiling was open save for wrought-iron work in stylized patterns jutting inward from the top of the walls. One entered the room from one side that contained an empty doorway with a scalloped arch on the top part. Walking into the room, one faced a large dolly (an object akin to The Rose) whose details became clearer with proximity. The remaining three inside walls contained some elements common with the dolly, placed in a sparse pattern or painted as trompe l’oeil on the concrete.

Seen from afar, the dolly’s surface seemed filled with holes that stood out as dark spots creating regular circular patterns. As one got closer, these were revealed as porcelain medallions imprinted with photographs of Turkish coffee cups with grinds that remain after the coffee has been drunk. The medallions were surrounded by intricate patterns containing curlicues and human figures in various postures. The piece’s design was dense enough to appear like a lace covering with complex motifs spread taut across the whole object. The minutely ornamented surface of the dolly contrasted with the rough, unpolished concrete of the wall it was mounted on. Turning to look around the room, one would notice the coffee cup medallions and much larger versions of the lace patterns placed sparsely across the remaining three walls. The room’s walls were blank on the outside.

The Grave of Time physicalizes crucial aspects of the way human beings create time. As reflected in the name, its basic structure recalls mausoleums large and small built over burial sites all over the world. The work’s form signifies the end point of the life of a particular embodied being, the person interred in the grave. Encasings of shroud, coffin, grave, and shrine over the perished body seem like an effort to arrest a transient object’s fleeting presence into a structure that could, with attention, last into perpetuity. In the case of the installation, the body is implied rather than present. The intricate contents of the walls seem to exteriorize social worlds that would go into the grave with a person who had died.

As in other situations aiming to capture time, the shrine’s solidity is a product of human manufacture. I would compare The Grave of Time to a narrative construct that would do through words what a shrine accomplishes in physical form. The analogy becomes deeper when we note that the images of coffee cups that form the surfaces of the porcelain medallions and are essential to the shrine correspond to unique events commemorated through photographs. Each coffee cup imaged here is different and contains the residue of a time when the coffee it contained was drunk as a social act undertaken in the presence of multiple people. The coffee cup images are unique events of the type that might make up a narrative about the past. They are placed within a lace-like web, which may be interpreted as referring to dense interrelationships between times and the people who might have experienced them.

The dolly and the wall surfaces of The Grave of Timecan be seen as a set of memories shared between a group of people. The space of the shrine is a limited commemoration since the people whose lives gave rise to it—and the ones whose eyes might see it— would be part of many other circuits of time as well that are not instantiated in the shrine. Like a book containing a narrative, the shrine’s walled enclosure corrals a portion of time. Its relationship to other times is open due both to the lack of corners and a ceiling and the fact that details of events recorded onto porcelain medallions are obscure to us save for the bare fact that they occurred.

Images of the cups and the lace are representations and not the original objects that were a part of the events. A similar pattern of irrevocable connection, yet necessary displacement, obtains in narratives about the past that must be imagined from presents. The fact that the images are of Turkish coffee cups makes the play on time richer still. The dried grinds we see on them come from the cultural practice of reading the future in them. When one is finished with the coffee, the cup is inverted upon the saucer and then turned back up to augur based on patterns in the residue. The image of each cup that we can see hearkens to an event in a present that came about due to relations leading up to it from the past and ended with the effort to imagine the future reflected in the grinds.

Photos of used coffee cups.

Photo courtesy of Lara Baladi

Photo courtesy of Lara Baladi

Photo courtesy of Lara Baladi

Diary of the Future

In an essay on her art practice, Baladi tells us that the tradition of reading time through coffee grinds acquired special significance for her as she accompanied her father in Cairo during 2007 in a house with a garden where she had spent parts of her childhood. Over months of her father’s terminal illness, the family was visited by relatives and friends. She instructed all of them to “drink, turn the cup upside down, turn it around three times in the saucer, and tap the top twice, then label with the date and your name.” She writes the following:

Every day, I carried the tray with the used and labeled cups outside to the table in that garden of my childhood. There, I photographed the inside of each cup—and the labels, at first, to keep track of whose each one was. But my eyes were so close to my subject, I fell into a kind of timelessness. I followed the ants walking on the saucers, became obsessed with the tiniest details, how the wet coffee dregs made patterns on the labels or how some of these labels were cut from my grandmother’s stack of hieroglyph-printed stationery, the same that she’d used for as long as I could remember. These photographs chart a period of great intimacy with my family and friends and the nurses and doctors who looked after my father. Assembling these fragmented moments into large-scale digital montages was like sewing, repairing life’s losses with the invisible thread that connects all things (Baladi, “Diary of the Future,” 140).

Baladi’s description of the genesis of works like The Rose and The Grave of Time correlates between the palpable loss of a cherished person and the enduring forms that came into being when she created the digital montages and the physical installation. The objects we can see acquire unique depths once we know the stories that led to their creation. Once created, the artworks have lives of their own, projecting toward future interpretations that might come from eyes looking upon them in unforeseen contexts. The aesthetic and conceptual content of Baladi’s work is, simultaneously, inextricable from the circumstances that led up to it and free and compelling to become part of other stories. One case for this is my saying that I have found her work an invaluable muse to think about time for this book.

In The Grave of Time, the visual encounter belongs to a plane distinctively more powerful than words. Its compactness and density invite engagement within the blink of an eye but can generate journeys with no end to them. While discursive expression can be correlated with images that represent pasts and futures, words cannot subsume what is possible in the visual domain.