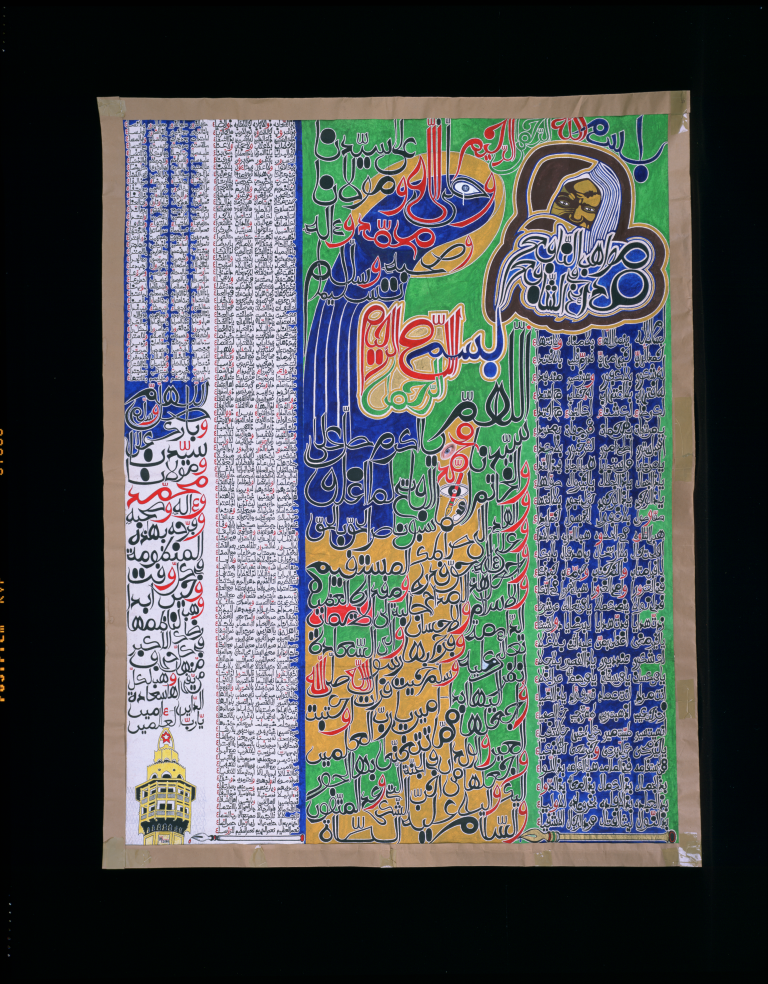

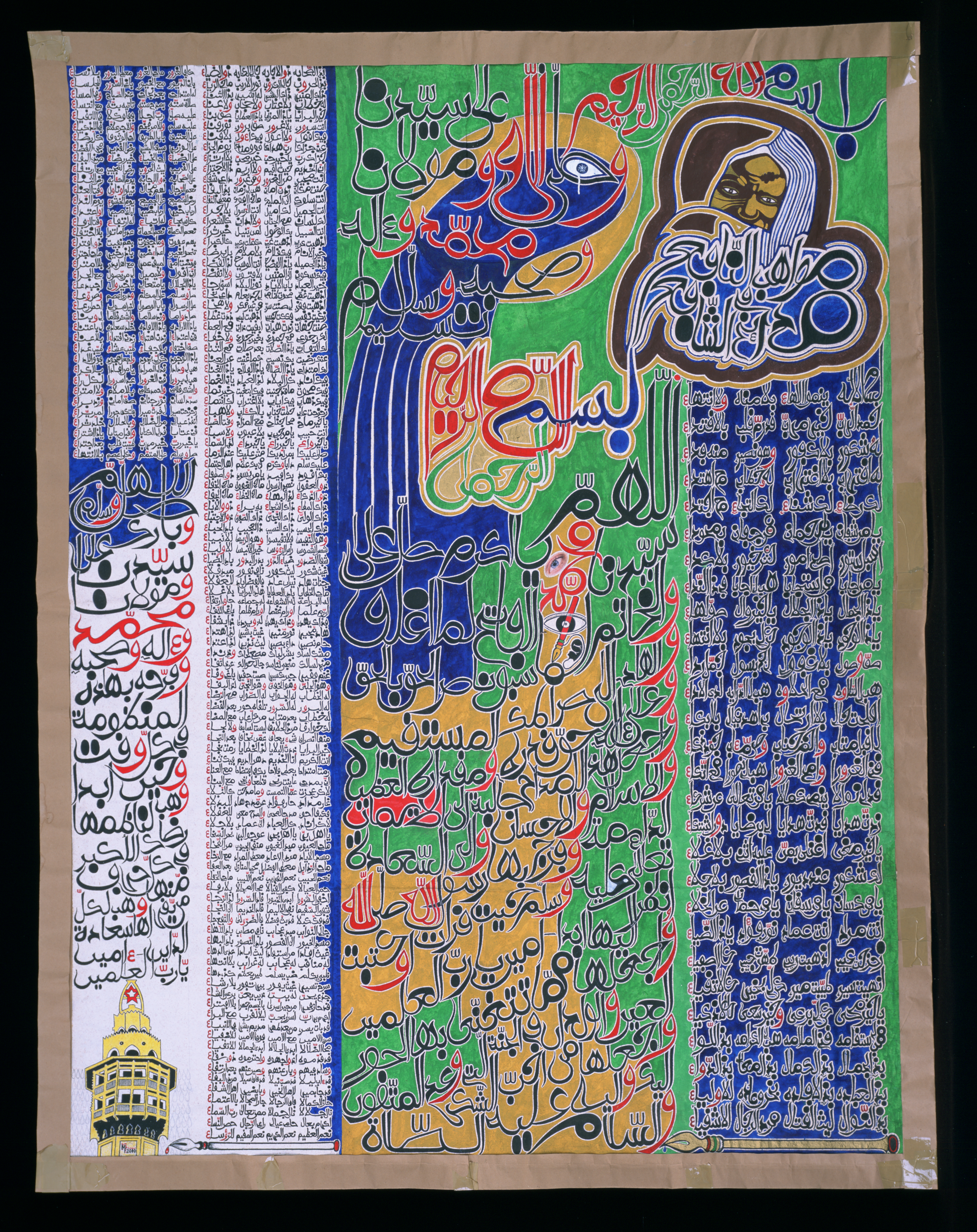

Captured between 1907 and 1927, a French colonial photograph has turned out to be a premier object of an Islamic group’s life in Senegal and its worldwide diaspora. This is a picture of Amadou Bamba (d. 1927), a charismatic Sufi leader who founded the community known as the Mourides in 1883. The photograph is the only known likeness of the man and was published in a book by an administrator whose charge was to describe Muslim groups in French West Africa for purposes of surveillance and colonial control (Marty, Études sur l’Islam au Sénégal, 1:221). The image acquired quite a different life from its intended purpose once Bamba’s followers excerpted it from the original source and began to replicate it endlessly in multiple forms.

The Mourides are a prominent community in Senegal and as migrants in numerous other countries. They constitute an extensive international network known for its prosperity and distinctive religious practices that overlap with expression in music and other art forms. Due both to his own eventful life and Mourides’ worldly success, Bamba’s biography and image have received extensive scholarly attention.

To consider aspects of Bamba’s image, we can begin with the following careful description of the photograph:

The black and white photograph shows a man standing in front of the wooden building. In the blinding daylight, Bamba squints in an effort to look at the photographer, whilst we too struggle to see his gaze enveloped in a dark shadow surrounding his eye sockets. As the Saint strains his eyes, his cheeks come up and his forehead crimps creating across his face strong shadows that alternate with achromatic areas reflecting the bright sunshine. A radiant white scarf covers his head, with one end falling at knee-height, and the other arranged across the face and over his shoulder concealing his mouth and chin. Made with the same immaculate textile, his abundant boubou reaches his ankles revealing one foot on a leather sandal. Echoing the garment’s flared shape, the bell sleeves are wide and hide both of Bamba’s hands. Alongside his hands, eyes, and mouth, the Saint’s right foot also disappears into an indistinct shadow of his full body on the uneven surface of the fine white sand (Paoletti, “Searching for the Origin(al),” 326–327).

In interpreting the photograph for religious purposes, Bamba’s followers have been especially attentive to the balance between the visible and the invisible in the image. Having seen a photograph like this, one would be hard pressed to recognize the person if they were to see his face in full or if he were wearing different clothes. But once the image is iconized—become a body onto itself—and widely replicated, the invisibility of half the face, the hands, and one foot becomes a mark of distinctiveness. The man’s partial hiddenness makes the image in the photograph highly recognizable.

As a still photograph, Bamba’s image is the record of a particular moment in the past, when the man stood in front of a camera in circumstances not known to us. Directly controverting this understanding, Bamba’s followers have seen it as an active agent in the various presents they continue to inhabit. In the religious interpretation, the only reason the photograph exists is because Bamba chose to make himself available, not to colonial authorities but for the benefit of his existing and future disciples. As the Mourides have seen it, the in/visibility of the man in the image makes him perpetually emerging and dissolving back into shadows.

The play of light in the photograph has infused motion into the still image, turning Bamba’s saintly body into a reflector transmitting divine blessings into the material sphere. For this reason, the photograph is seen as Bamba’s gift to the world. The image is replete with baraka, here understood as “an active energy that heals, protects, and helps them in countless other ways. Mourides often brush their fingertips over or kiss Bamba’s portrait, or touch smaller images to their foreheads to receive God’s baraka from the picture” (Roberts and Roberts, “Mystical Graffiti and the Refabulation of Dakar,” 56). For all these activities, constant replication of the image is a necessity. This is a case where making copies enhances the potential of the original.