Time Travel

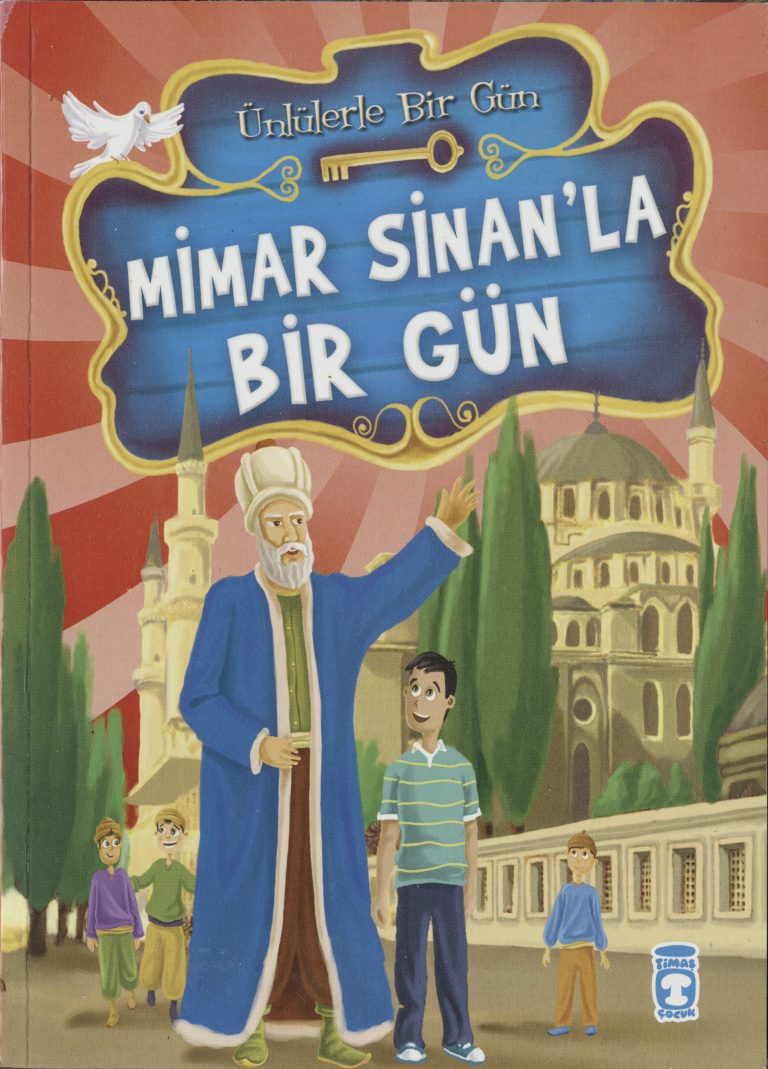

The Süleymaniye mosque and its architect, Sinan, are the stuff of legend. To appreciate their wide significance for Turkish identity, I will discuss a children’s picture book entitled A Day with the Architect Sinan (Mimar Sinan’la Bir Gün) by Mustafa Orakçı that was first published in 2009. The book is part of a series of ten books by the same author (ten more were published in 2015) entitled A Day with Famous People (Ünlülerle Bir Gün). Meant for children seven years and older, the series contains self-described adventures of a boy named Murat who is especially interested in history and wishes to meet famous people from the past.

In the frame narrative that is repeated in each book in the series, Murat says that one day as he was looking out from a window at home, a pigeon landed on his hand, with a key in its beak and a note tied to its claw. The note stated “Where do you want to go? To the past? Then take the key in your hand, close your eyes and imagine.” From then on, upon following the instructions, Murat was magically transported to the time of people about whom he was learning in school. His conversations with luminaries are narrated in words and depicted in pictures, allowing him to convey his special access to the past to other children. The time travel ruse turns the abstract past given in textbooks into relatable experience seen and felt by children.

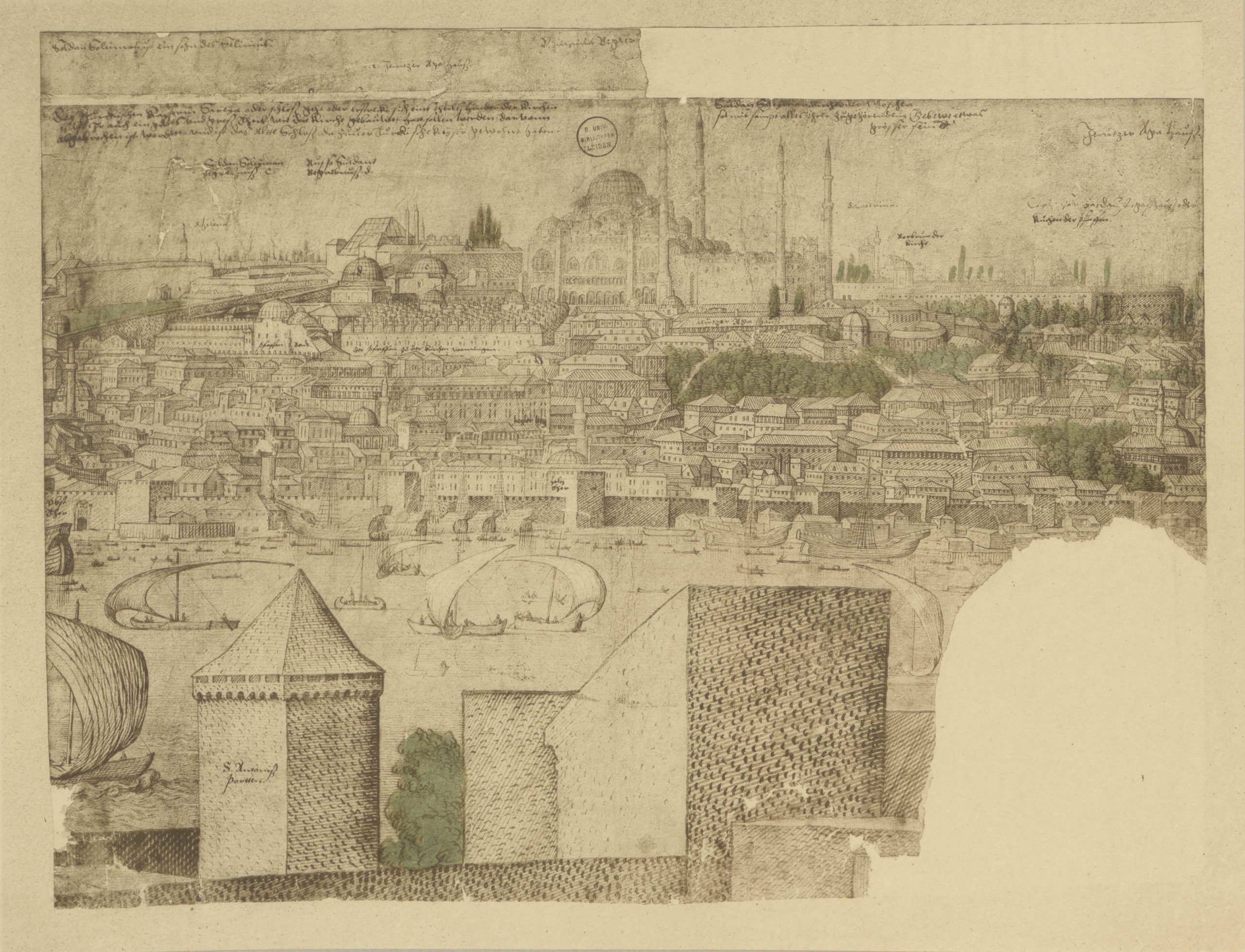

The cover of the book that describes the encounter between Murat and Sinan has the two pictured in front of a silhouette of the Süleymaniye’s facade and minarets. The boy decides to activate his special key upon visiting the mosque complex on a school trip. The mosque as experienced in the twenty-first century thus becomes a time machine for transport to the situation in which it originally took shape.

children

A day with Mimar Sinan.

SOURCE

Mustafa Orakçı, Mimar Sinan’la Bir Gün (Istanbul: Timaş, 2014)

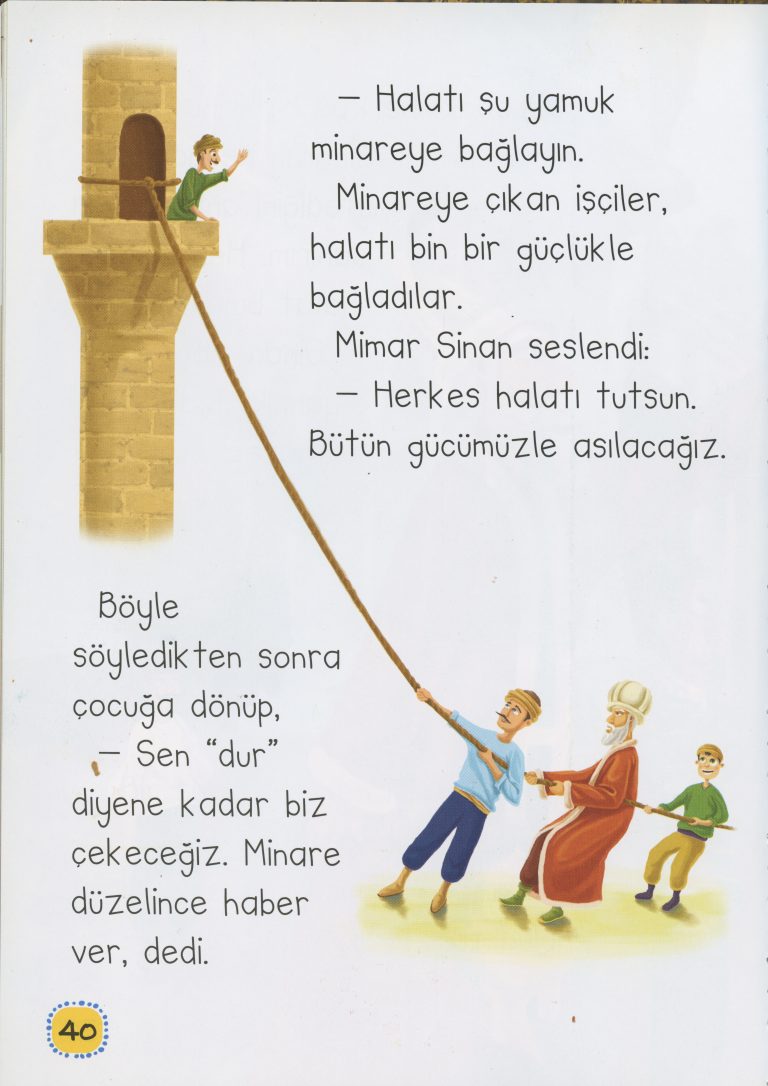

Straightening the minaret.

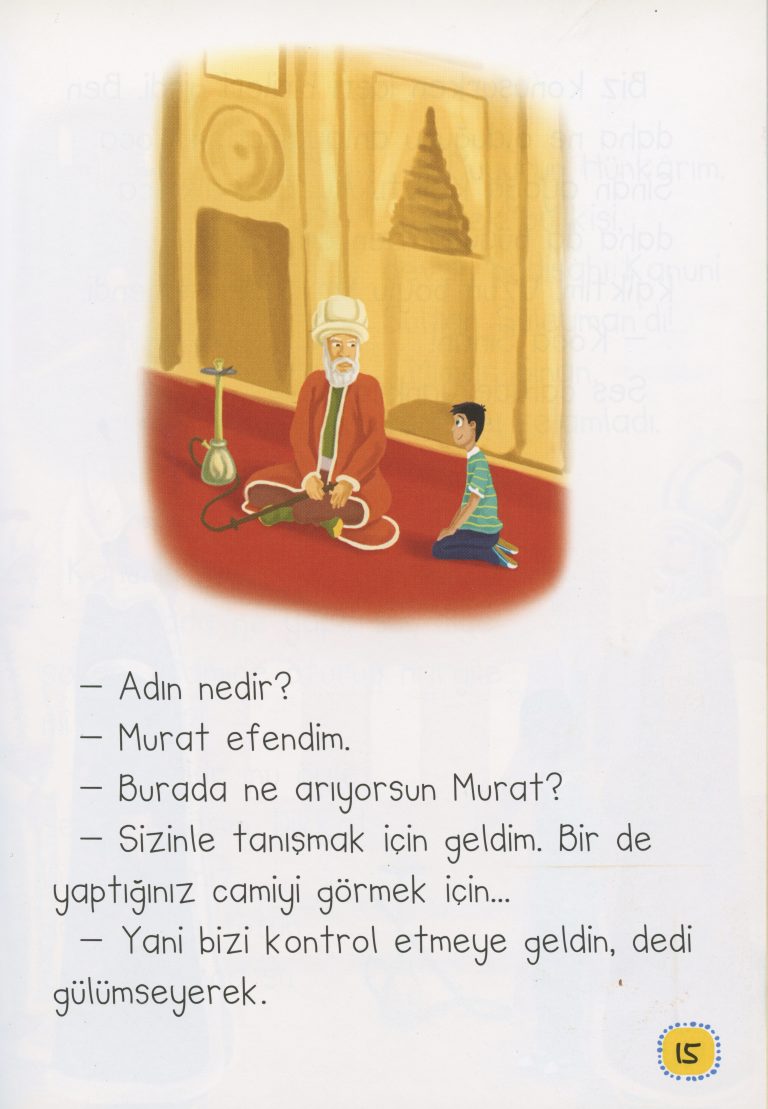

Conversing in the Süleymaniye Mosque.

Go to next slide

Go to next slide

Upon arrival in Sinan’s time, Murat encounters some laborers who direct him to the architect sitting inside the mosque. The temporal point of entry in the past is a moment when the mosque already exists in the form in which it would remain for centuries hence. Murat’s time with Sinan works as a conspectus orienting us to matters such as the architect’s life history, his close identification with the Ottoman ruler Süleyman (d. 1566) who commissioned the great mosque, and some of the mosque’s physical features.

Murat finds Sinan sitting in the mosque’s sanctuary with a water pipe. He thinks to himself that this does not seem proper for a religious building. His thought is ratified when Sultan Süleyman appears unexpectedly and berates Sinan. The architect responds that the water pipe has no tobacco and he is just blowing through water to create sound to check the building’s acoustics. Upon hearing this clever trick, Süleyman compliments the architect and compares his greatness to that of the building and the empire (Orakçı, Mimar Sinan’la Bir Gün, 13–18).

Most of the book consists of Sinan answering Murat’s questions regarding how buildings are made and Sinan’s path to becoming an architect. Recalling his travels as an Ottoman soldier before being appointed the chief architect in Istanbul, Sinan states that it was when he saw the pyramids of Egypt that he said to himself, “The buildings I will build will also last until the day of Resurrection!” (33).

The book ends on an incident in which children become a major part of the mosque’s story. As Sinan and Murat are talking, they are called outside where a boy is claiming that one of the mosque’s minarets is tilting. Rather than simply telling the boy that the claim is manifestly false, Sinan goes along with the criticism and asks for a rope to be tied to the top of the minaret and pulled from the ground. This procedure continues until the boy agrees that the minaret has been straightened. When asked why he played along, Sinan replies that what the boy was saying could have caught on and the mosque may have become known as the one with the tilting minaret. By acquiescing, he had satisfied the boy while also saving the mosque’s future reputation (45). Following this incident, Murat leaves the company to go to a quiet place and asks the key to take him to his own time.

Mimar Sinan's mausoleum, Istanbul, Turkey.

Source

Mimar Sinan's mausoleum, Istanbul, Turkey.

SOURCE

Wikimedia, Pamukova Haber, 2019 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Back in modern Istanbul, Murat joins his schoolmates as the group makes its way out of the Süleymaniye complex. They pass by a small building, and their teacher tells him that this is where Sinan is buried. The book ends on a sentence left unfinished: “The modest mausoleum of Koca Sinan, the builder of enormous buildings.” (47).

In Istanbul, where Murat lives, Sinan’s marks on the landscape are inescapable. They range between Sinan’s own work, such as the Süleymaniye, and hundreds of other mosques that resemble it and have been constructed over half a millennium. The children’s books on Sinan and the other mostly Ottoman-era characters covered in the series A Day with Famous People are a sophisticated attempt at rendering a highly valued past “real” for citizens of modern Turkey. The story pertaining to Sinan builds a narrative around a material form present pervasively in expected readers’ field of vision. The form is primary, encountered daily irrespective of a narrative attached to it. The children’s book provides stories that give it a particular coloring based on twenty-first century pedagogical objectives.