Islamic time is a conglomeration of mutable and malleable horizons that fold diverse pasts and futures into themselves. Substantiating this view requires that we understand the object of inquiry nominally; that is, Islam is a matter of naming rather than determining substances. Islam is found wherever it is invoked by name or inference, without an expectation of systemicity or internal coherence. Coming across evidence, we must first register Islam’s presence through name and then attempt to constitute its meaning through close examination.

I contend that the nominal approach is the optimal way to think historically about Islam. Being named “Islamic” by someone, somewhere, is the sole criterion that stretches across all the evidence I present in this book. By thinking nominally, we allow our imagination to mold to the evidence pertaining to Islam in all its diversity. Doing so avoids confining Islam to regions, time periods, and topics in an a priori way. Limitations rooted in presumptions pertaining to such factors are counterproductive and easily falsified when we consider the totality of data available for Islam. Moreover, naming oneself, others, and objects put to analysis is a crucial matter central to comprehension. Far from being trivial or superficial, naming is the core issue that has made “Islam” a consequential and powerful term in human affairs for centuries.

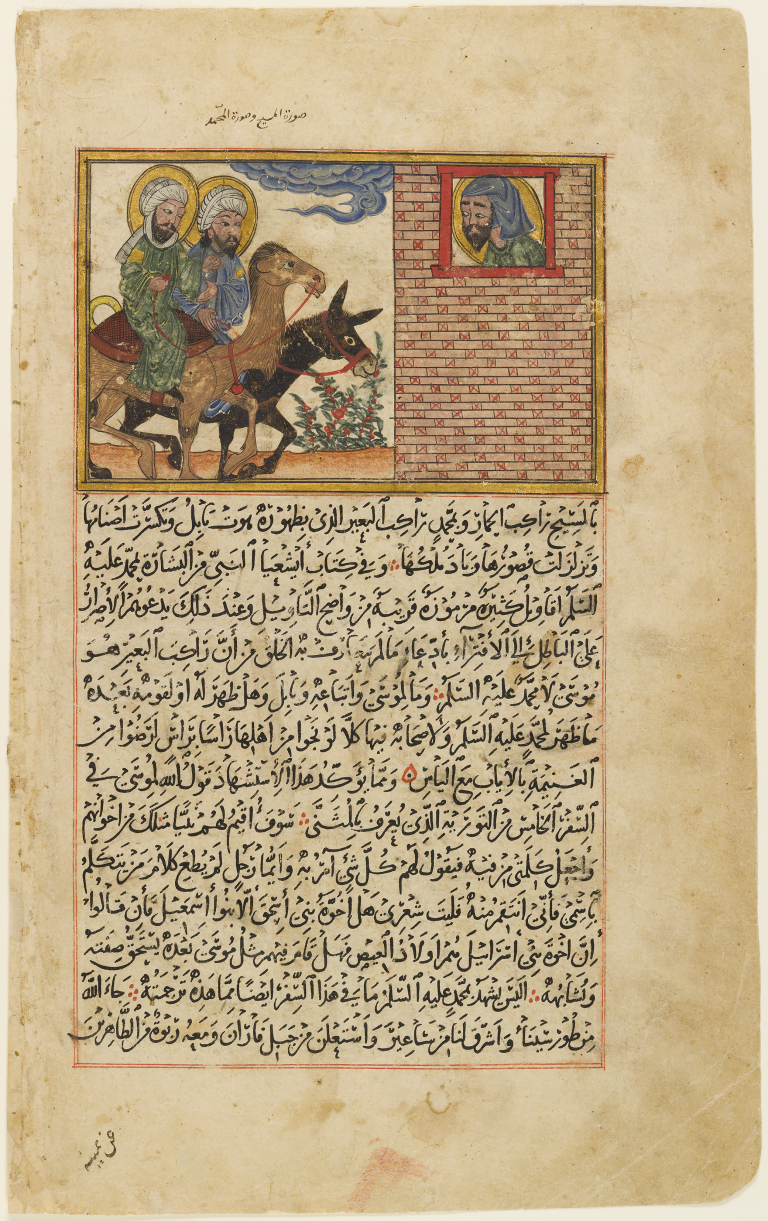

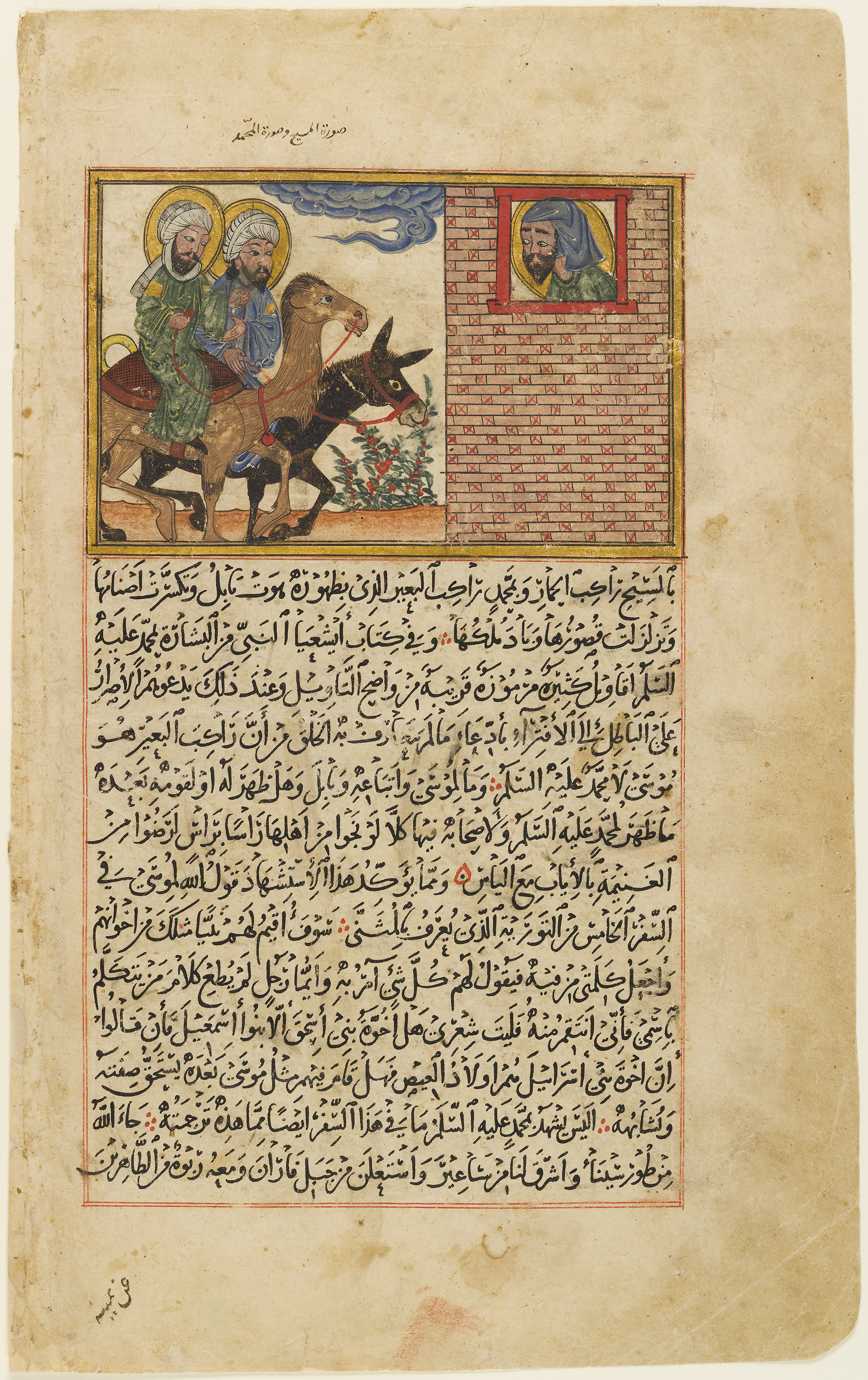

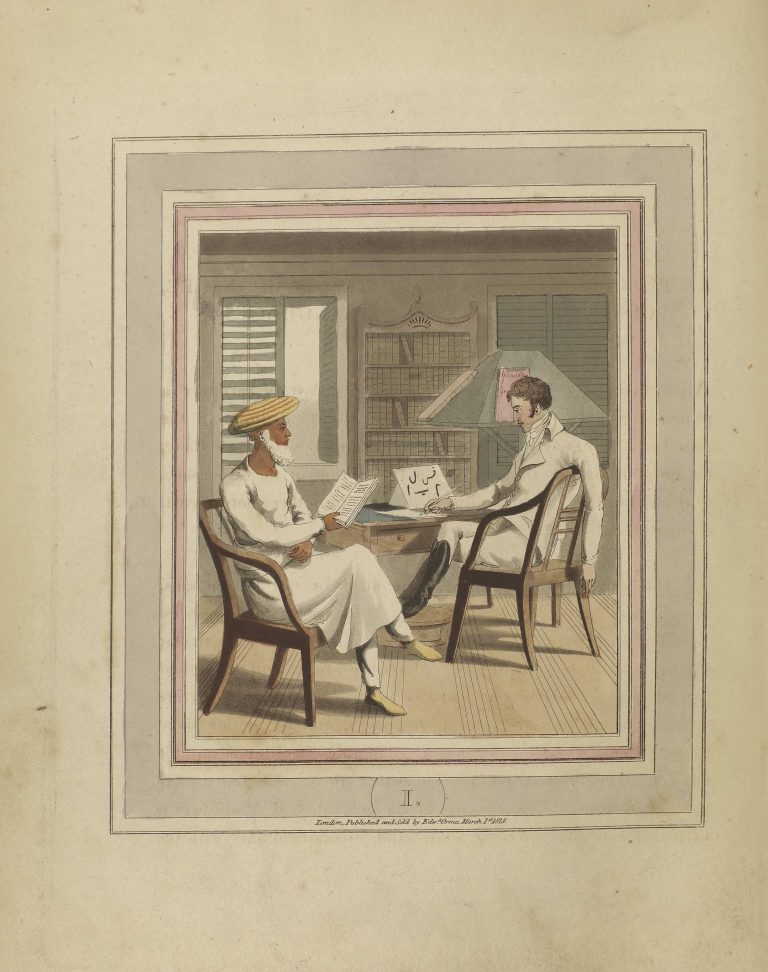

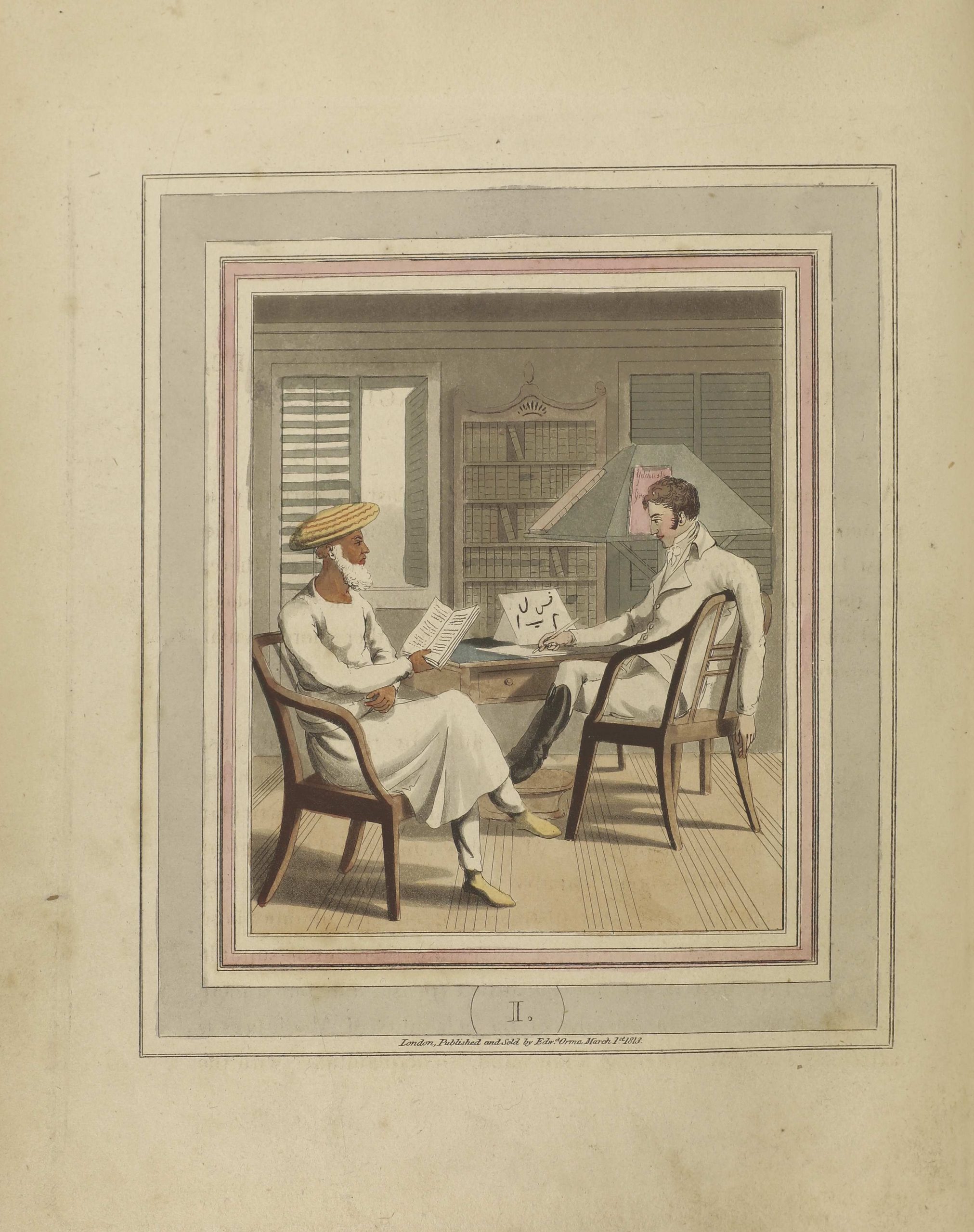

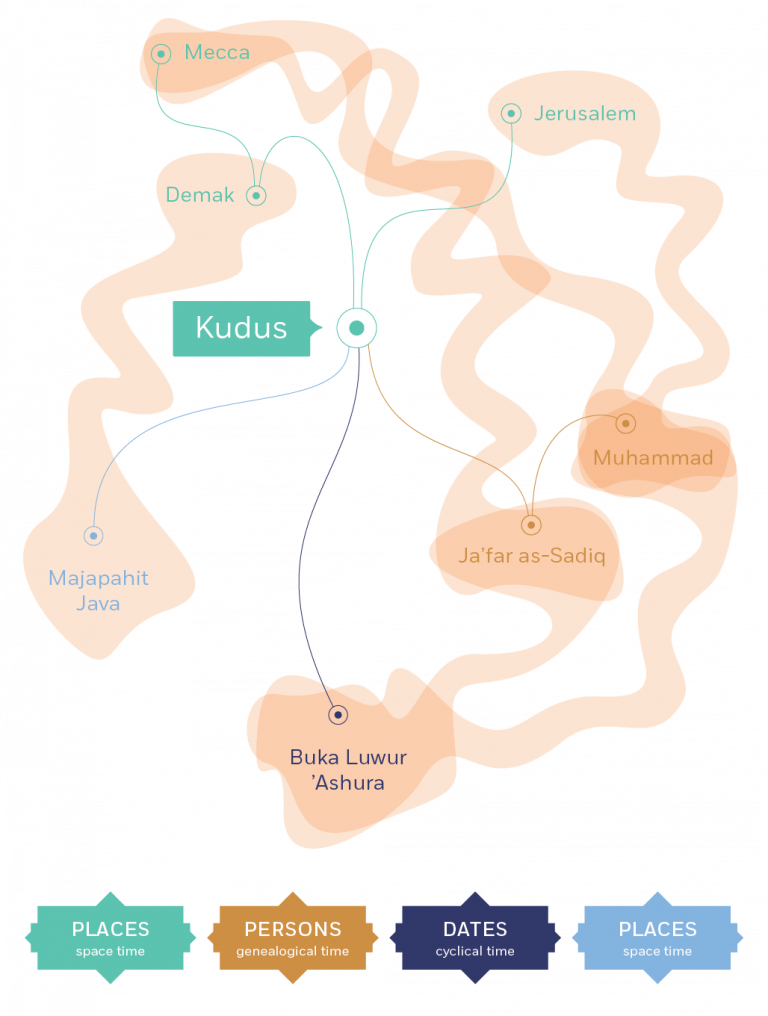

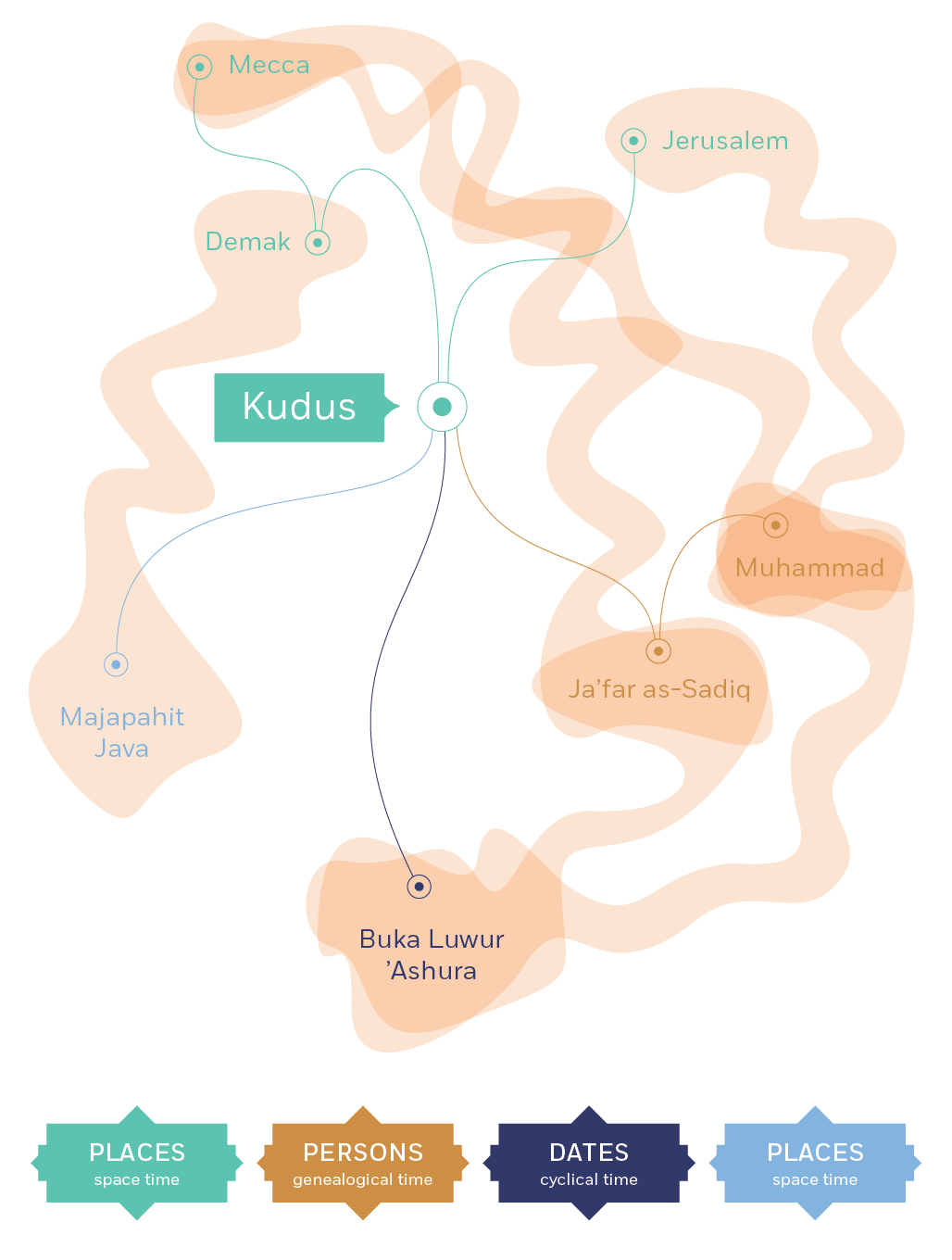

Within a nominal understanding, Islam is both phenomenon and discourse. It consists of elements that human beings experience and discuss in language. As phenomenon, Islam is encountered through experience involving entities that have aspects that are presented to our senses and faculties of apprehension. These can be observed in the built environment, material objects, paintings, linguistic traces that are heard or read, narratives that substantiate individuals or communities, and composite social situations involving experience, such as politics. Very often, a single phenomenon contains any number of temporal elements that can be teased out through attention to the pasts, futures, and horizons discernible in its details.

As phenomenon, I can identify Islam’s presence in particular evidence, either due to projections made in the materials or my assessment based on prior experience. Islam is simply a part of the world we can observe and experience in its full diversity. There is no reason to expect Islam as phenomenon to be coherent or consistent. Any coherence we attribute to it as phenomenon derives from the analytical scheme we bring to the evidence to render it meaningful for the specific purposes we have decided to privilege in a given situation.

Analyzing Islam as phenomenon requires resorting to frameworks for making meaning that have given rise to modern academic disciplines such as phenomenology, history, anthropology, and sociology. Methods used in these disciplines lead to bounded assessments of the material and social worlds we can apprehend. Coherence in these assessments is a function of the analytical tools. The evidence itself is far too diverse, incidental, and conflicting for Islam to be understood as a bounded system.

Islam is also articulated discourse, a result of human thought regarding words inherited from others and the experience of phenomena. As discourse, Islam is found in theology, philosophy, political systems, texts in oral and written form (i.e., words put into determined order to produce images and systems), and so on. Interpreting Islam as discourse requires recourse to various branches of narratology (philosophical and literary analysis) and lexicons and terminology.

In assessing discourse, we may attend to questions of coherence and incoherence, consistency or lack thereof, slippages, and so on. However, we cannot presume that all the discursive evidence we have for Islam coheres into a unified, describable system. As in the case of phenomenon, Islam as discourse is too wide-ranging and conflictual to warrant such an assumption. Whenever an attempt is made to force all discursive evidence pertaining to Islam into a coherent system, the result is a hierarchizing ideology that is unwarranted, prejudicial, and easily refutable.

Phenomenon and discourse are interdependent categories that are engaged concurrently in complex analysis. In objects, time can be the signature of the moment of production as well as the difference between when the objects were produced and what we make of them today based on a change of horizons. In discourse, narratives are time bound by definition as they unfold in successive moments, have horizons, and deploy pasts and futures for diverse purposes.